President Donald Trump is planning to lower company tax to 20 per cent, the British Conservatives will be lowering their company tax from 20 per cent to 17 per cent by 2020, the Netherlands is cutting from 25 per cent to 21 per cent by 2021, and even French President Emmanuel Macron is promising a 25 per cent company tax by 2022.

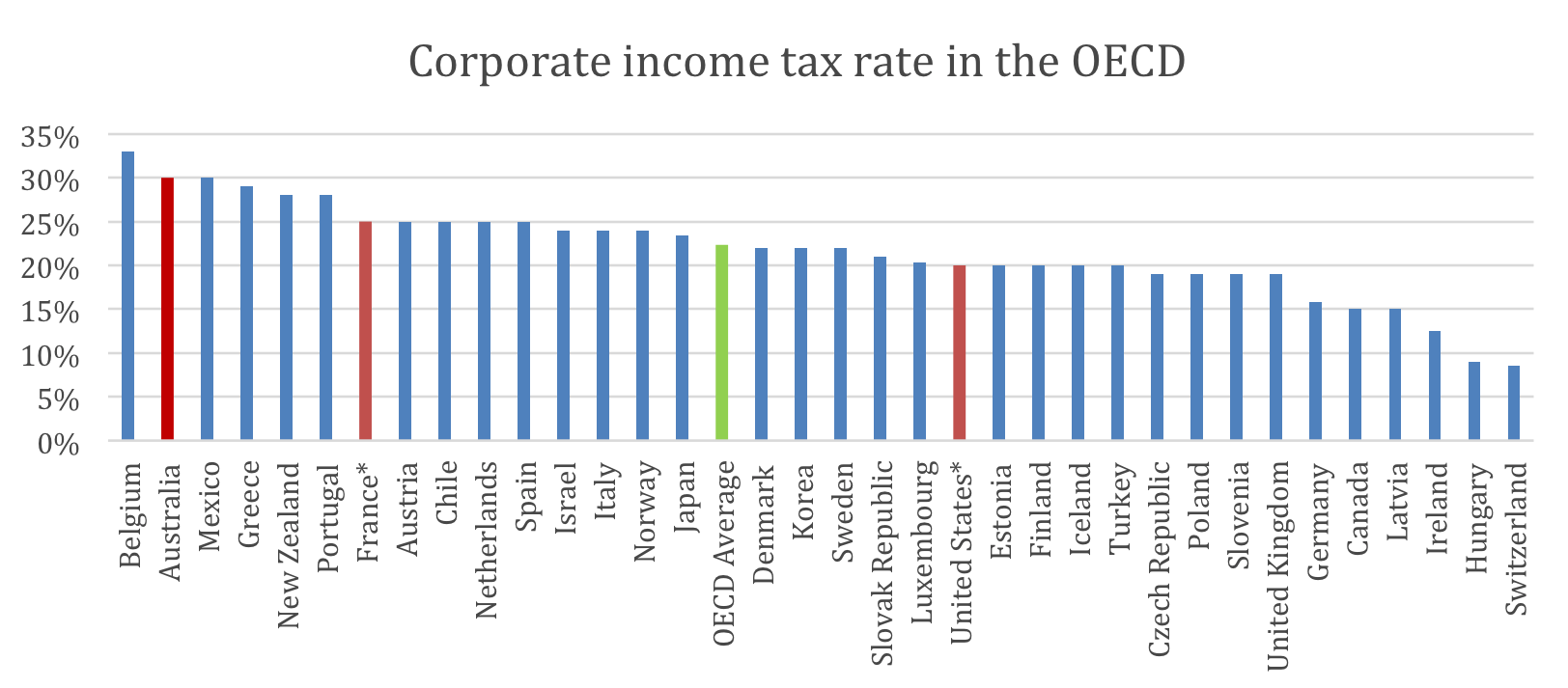

Australia is falling behind. Our 30 per cent company tax rate (and 27.5 per cent for small businesses) is well above our competitors and other developed economies. The OECD average now stands at 22 per cent, and trending downwards. Australia has the fourth highest corporate tax in the OECD. And, after planned changes in the US and France, Australia will have the second highest. In our region, Singapore’s company tax is just 17 per cent, and Hong Kong’s is 16.5 per cent.

*Planned changes to company tax. Source: OECD

*Planned changes to company tax. Source: OECD

It may appear at first that companies pay company tax – but this is a deception. Companies are not people, and must pass along the cost of the tax through higher prices, lower wages or reduced returns to investors. A high company tax also discourages investment and entrepreneurship in the first place – because potential returns will be lower.

As part of the Henry Tax Review process, KPMG developed modelling which found that the company tax is the most burdensome federal tax. The modelling found that for every dollar of company tax raised there is 40 cents less economic activity.

This largely because, in a competitive global market, company tax discourages investment in Australia and therefore dislocates economic activity. That is, according to KPMG, ‘capital is highly mobile internationally and the supply of foreign capital to Australia [is] very sensitive to its rate of return. Thus, when company tax is increased, the required pre-tax rate of return increases leading to a fall in (foreign) investment.’

Australia’s disproportionally high company tax means less business creation and therefore fewer jobs. The lower investment in capital means lower productivity and incomes for workers. For consumers, a high company tax means higher prices and fewer products and services on the market.

Since KPMG did their modelling in 2009, company taxes elsewhere have fallen. As a consequence, Australia is an even less attractive place to invest.

The Howard government was ahead of the global curve by lowering the rate to 30 per cent in 2002, however, the lack of substantial action since (with the exception of a reduction for small businesses) puts Australia out of line with our competitors and other developed economies.

And, while the KPMG modelling is theoretical, there is plenty of historical evidence on the impact of company taxes.

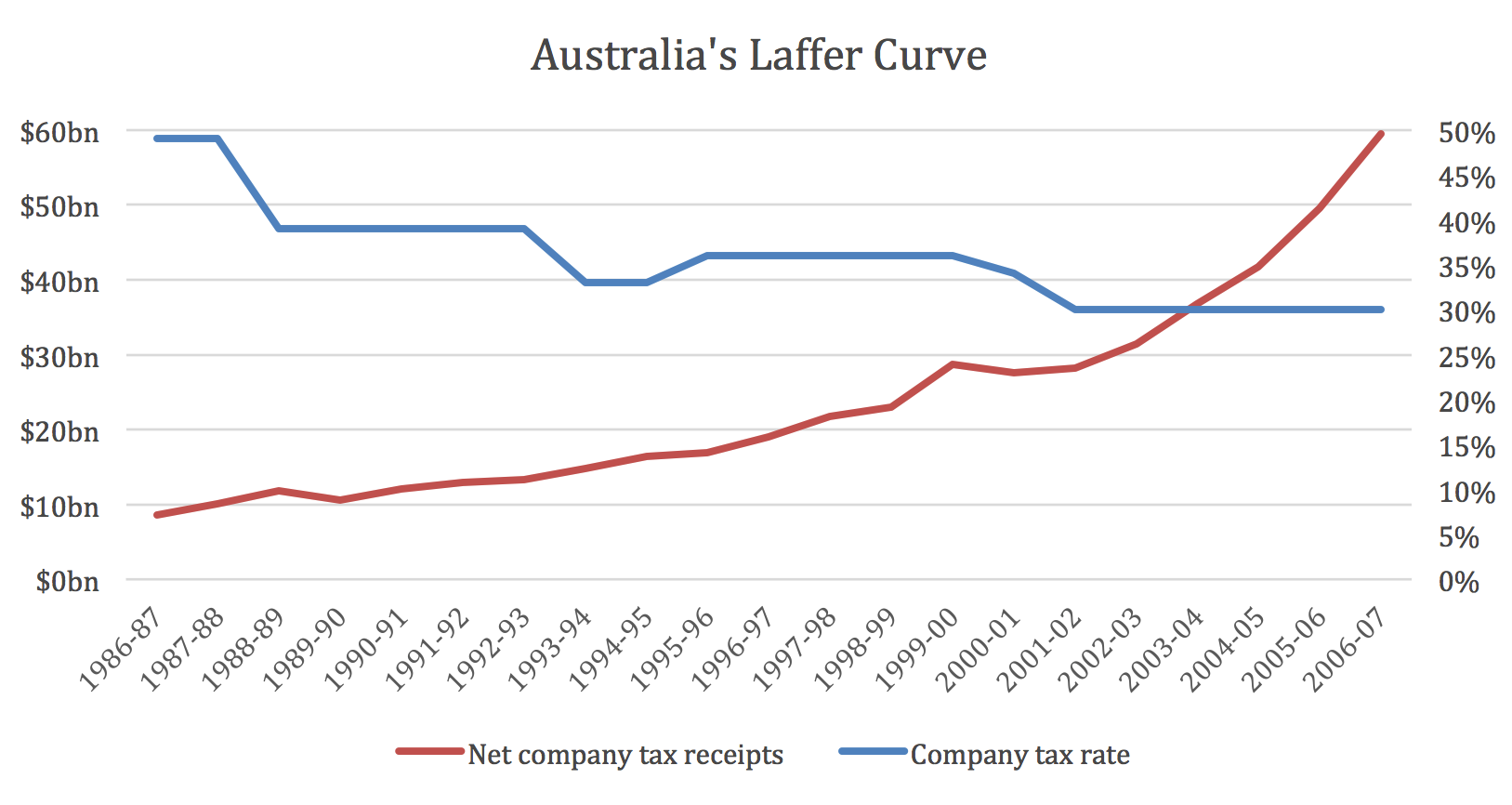

Source: Australian Tax Office

Source: Australian Tax Office

Between 2000 and 2002, Australia’s company tax rate was lowered from 36 per cent to 30 per cent. In the immediate period, government company tax receipts remained stable at about $28 billion. However, this did not last long. The lower company tax was correlated with skyrocketing revenue over the subsequent years. By 2005 it had reached $42 billion, and about $60 billion by 2007.

It is, of course, no coincidence that this revenue upshot came during the mining boom in Australia – and plateaued during the Global Financial Crisis. Nevertheless, what is clear throughout the data set is that the lowering of company tax from 49 per cent in 1987 to 30 per cent did not lead to lower government revenue. In fact, the opposite is true: the company tax revenue stabilised and then subsequently grew.

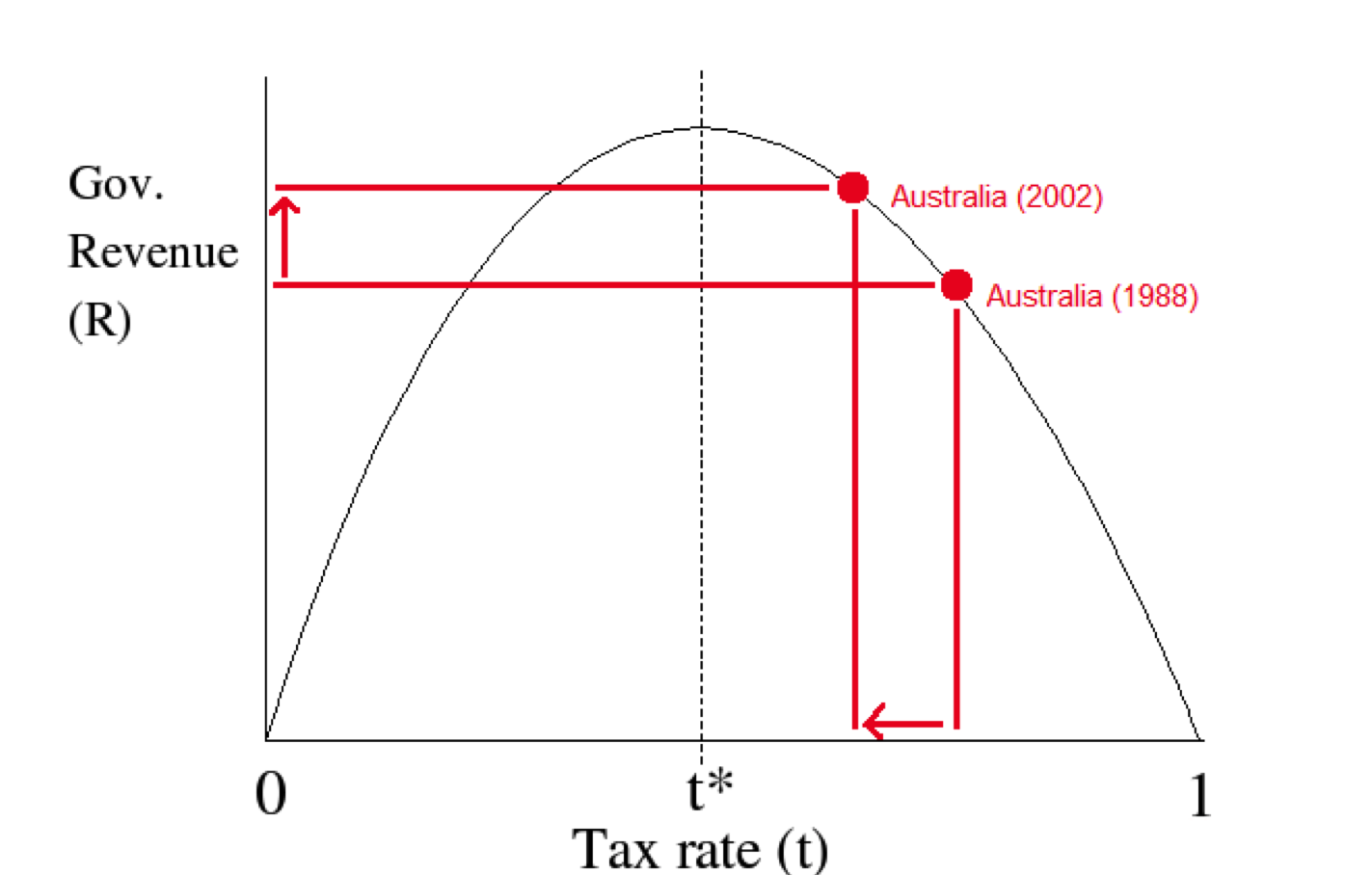

As can be seen in the classic Laffer Curve (above), a decrease in the company tax rate can lead to an increase in government revenue. This is because a lower company tax increases economic activity – more businesses, more jobs, higher incomes and more people paying tax – and not just company tax, increased economic activity means additional revenue from payroll, income, consumption and other taxes.

As can be seen in the classic Laffer Curve (above), a decrease in the company tax rate can lead to an increase in government revenue. This is because a lower company tax increases economic activity – more businesses, more jobs, higher incomes and more people paying tax – and not just company tax, increased economic activity means additional revenue from payroll, income, consumption and other taxes.

The wide-ranging evidence is clear, from Britain in recent history to comparative analysis of US states, and even Islamic State; lower tax rates are linked to more economic activity and therefore higher revenues in the long run. The message is clear: lower taxes are a win-win for the economy and the government.

The Australian Treasury has even projected that the reduction in company tax to 25 per cent would increase revenue by $30 billion, due to the economy growing one per cent faster in the long term.

The challenge for the Turnbull Government, which has previously given up on tax reform, is to make the case for a lower company tax – or risk Australia becoming an even less hospitable place to invest, threatening the government’s mantra about ‘jobs and growth’.

Matthew Lesh is a research fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in