The Greek historian, Thucydides, who lived through the Peloponnesian wars, wrote that: “The bravest are surely those who have the clearest vision of what is before them, glory and danger alike, and yet notwithstanding, go out to meet it.”

This was certainly so of many men who served as Senators and MPs in the Australian Parliament throughout most of the 20th century. In fact, 119 men who were, or would go on to be Federal Parliamentarians, served during the First World War. These included three VC winners, at least five generals, and two future Prime Ministers.

Theirs was the generation who took their experiences of war and turned them into the tools with which to forge a post-war Australia. Theirs also was the generation who demonstrated that courage on the battlefield could be turned into the courage needed to make hard political decisions.

However, Greens Senator Di Natale clearly does not agree.

His extraordinary attack this week on former Major-General Jim Molan, now Senator Molan – accusing him of using “hunger and a deprivation of water as a weapon of war against the civilian population, a flagrant violation of international law” – was not only wrong, but marked the first time that service of one’s country, along with moral and physical courage, have been deemed disadvantageous to Australian public life.

Yet the skills involved in prosecuting a successful war – careful planning, overcoming unexpected adversities, single-minded focus on objectives, and the ability to lead and inspire – are the very qualities we should expect of our political leaders. They are certainly a better qualification for office than anything Senator Di Natale and most of his colleagues can offer.

His comments also mark a critical stage in the increasing intolerance of the Greens. Previous Greens, like former Senator Jo Valentine, were always careful to distinguish between their dislike of wars and disliking the people who were called upon to fight them. Di Natale is not.

His accusation was as wrong as it was deplorable.

As Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations in Iraq, Major-General Molan was responsible for planning the assault on Fallujah in November 2004, after the city had been taken over by insurgents, and the civilian population terrorised into submitting or fleeing the city entirely. The insurgents had no intention of abandoning their stronghold, and therefore the only course of action was to drive them out. War rarely offers many alternatives.

It is to Jim Molan’s credit that all times this was conducted according to the laws of armed conflict. Critical to Molan’s planning for taking Fallujah was the care of any remaining civilians in the city. Before the assault began, Molan had in place fifteen days of bottled water, and medical kits to support 20,000 people for 90 days. There was also immediate food for 10,000 people, plus another 220,000 meals ready to be shipped in from Kuwait. These are hardly the actions of a war criminal.

Senator Di Natale is also tragically ignorant of the realities of fighting an urban war against insurgents who have taken over a major city. If anyone was violating international law, it was the fighters who were using civilians as human shields, not the uniformed men and women who were fighting and dying to free them.

Acknowledging that would, however, have been an inconvenient distraction from his preconceived narrative that confuses the military with militarism, and fighting wars with violating international law.

Senator Di Natale’s political problems, however, are far greater than his unconcealed disdain for our men and women in uniform. He fails to properly understand the unique relationship between those who do our nation’s bidding, and those who collectively send them.

At the time of the First Gulf War, I was a 25-year-old Senator faced with the fundamental moral dilemma of whether or not to vote for sending Australians to war.

Having grown up as a young boy in the shadow of the Vietnam War, I had always assumed that if Australia ever again went to war, my friends and I would be conscripted, and someone much older would be sending us away. Instead, I was the one being asked to decide.

After much agonising, I called a friend from Oxford, who had taken a commission in the British Parachute Regiment, and asked him whether I could morally vote to send people my age to a war in which I would not fight. His answer was simple, and to the point: it was his job to go if people like me asked him to go, and it was my job to ask him to go if it was the right thing to do.

That was the same of the Australians we sent away to the First Gulf War, and every war before or since.

This trust relationship – the most sublime in Australian public life – is only possible because of the willingness of our service personnel to not only risk death in carrying out our nation’s wishes, but to forego exercising their own political judgment in the matter.

However, that trust relationship is as fragile as it is profound. Just as our armed forces must collectively implement the will of our politicians, our politicians must collectively support those who do their bidding.

For decades after the end of the Vietnam War, the ADF bore the deep psychological scars of betrayal by politicians who scapegoated soldiers for their own political opposition to the war. In my view, having spoken to scores of such men, these psychological scars are sometimes as deep as the experiences of war itself.

Senator Di Natale is now guilty of the same political intolerance. Unless countered, it runs the risk of scarring not just Jim Molan, but the thousands of Australian soldiers, sailors and air force personnel who have fought in Iraq, and Afghanistan too.

Accusing a soldier of war crimes is as grave as accusing a politician of being corrupt in public office; accusing a general of violating international law also accuses all those who served under him, and carried out his orders.

None of this is new for Senator Di Natale, however, who has a long history of decrying, or at least suspecting, war crimes by Australian personnel serving overseas. For all of this, he has no military service to serve as the basis for his preconceptions.

This impediment is not beyond remedy. It would always be open to him, as a medical professional, to offer to serve alongside our troops overseas. Senator John Herron did as much when he deployed as a doctor with Australian troops in Rwanda.

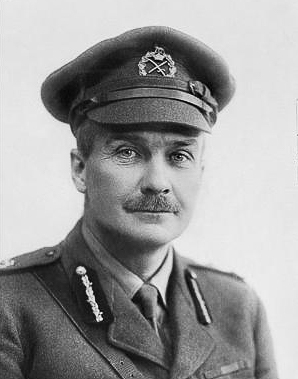

In so doing, Di Natale could measure his courage alongside that of Sir Neville Howse, who served as an army doctor in the Boer War and the First World War, and who received a VC for saving a wounded soldier under intense fire, and carrying him to safety. Equally, he could test his perseverance against Sir Earle Page who was Chief Medical Officer on the troopship HMAS Ballarat before serving at clearing stations in France.

Sir Neville Howse VC/Boer War Memorial.

Sir Neville Howse VC/Boer War Memorial.

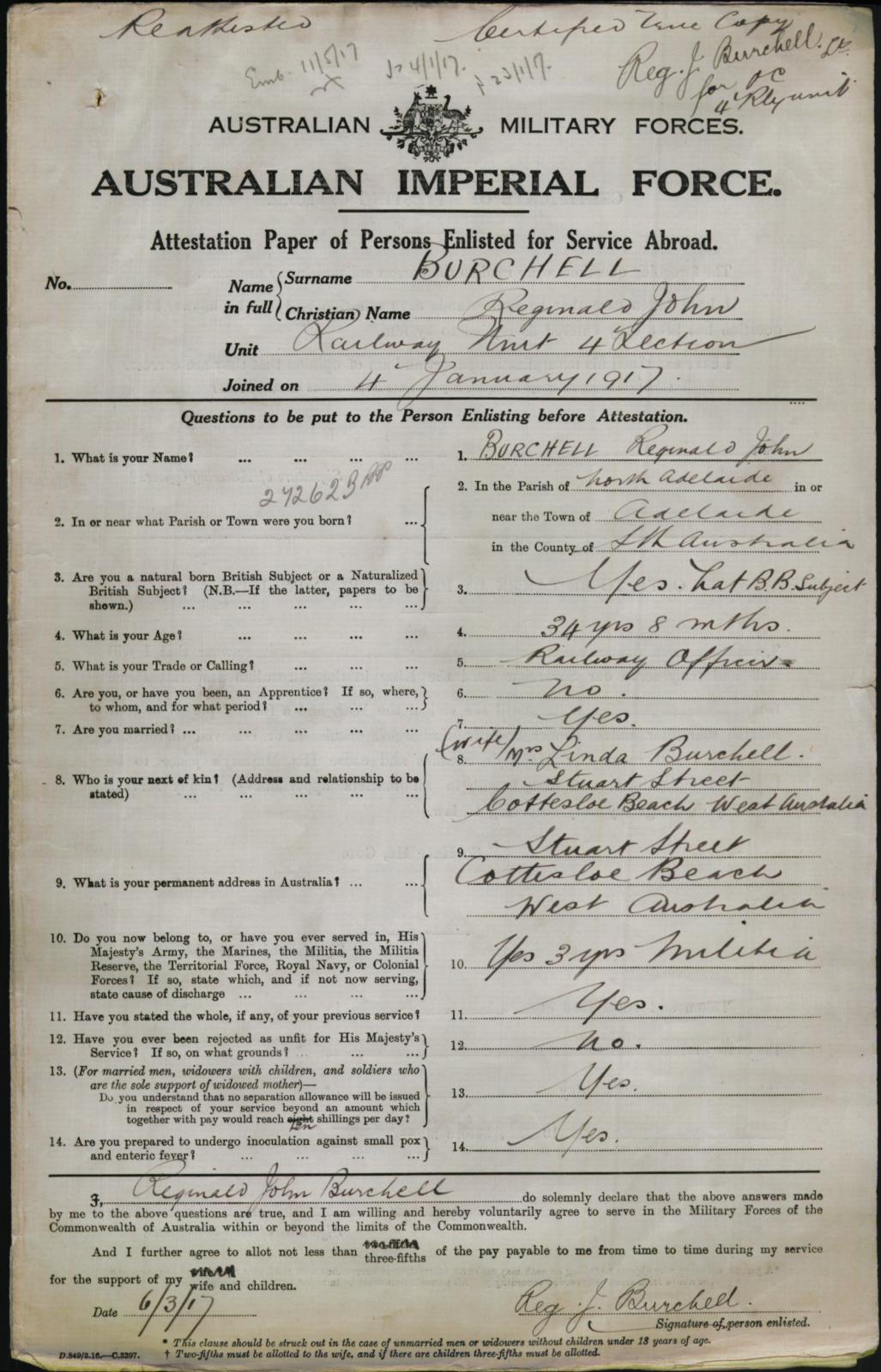

Reginald Burchell was a Member of the House of Representatives when he joined in 1917, simply listing his calling as a railway officer. He later won a Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry in France. Another politician to enlist was 62-year-old James O’Loghlin, a Labor Senator from South Australia. Notwithstanding his opposition to conscription, and his refusal to abandon the Labor Party to join Billy Hughes, he volunteered for service and was sent as an officer commanding reinforcements to Egypt Gallipoli and France.

Reginald Burchell’s enlistment form, stating his calling as Railway Officer/National Archives of Australia.

Reginald Burchell’s enlistment form, stating his calling as Railway Officer/National Archives of Australia.

As it is, Senator Di Natale looks increasingly like a pestersome popinjay in a Shakespearean play. He proclaims his own political courage while scorning those who serve in our wars; he demands a greater say over our involvement in war, but cannot enunciate the grounds on which he would ever vote to do so.

When the Islamic State movement and its allies are defeated, as they eventually will be, it will not be because of anything he has done. Jim Molan, on the other hand, can hold his head up high, as can those who have served alongside and under him.

Thucydides, in his history, didn’t just address the qualities of bravery, but also those of inaction. He wrote: “If you have the power to put a stop to subjugation, yet look the other way while it happens, then you have done it yourselves.” Senator Di Natale should take note.

Bill O’Chee is a former Australian Senator and former Australian army officer.

Main illustration: Defence photograph.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in