Last week, I came across a figure so staggering that I was convinced it was wrong: 5.3 million Brits (almost the population of Scotland) are on out-of-work benefits. How could this be, with ministers so regularly boasting that unemployment stands at a 40-year low? How could it be, when a national shortage of workers has been declared – and the aviation industry has been begging the government to relax immigration rules, saying that we’re out of workers?

I’ve spent this week looking into it, with the help of my brilliant colleagues in The Spectator data team, and look at this in my Daily Telegraph column today. Here’s what I found.

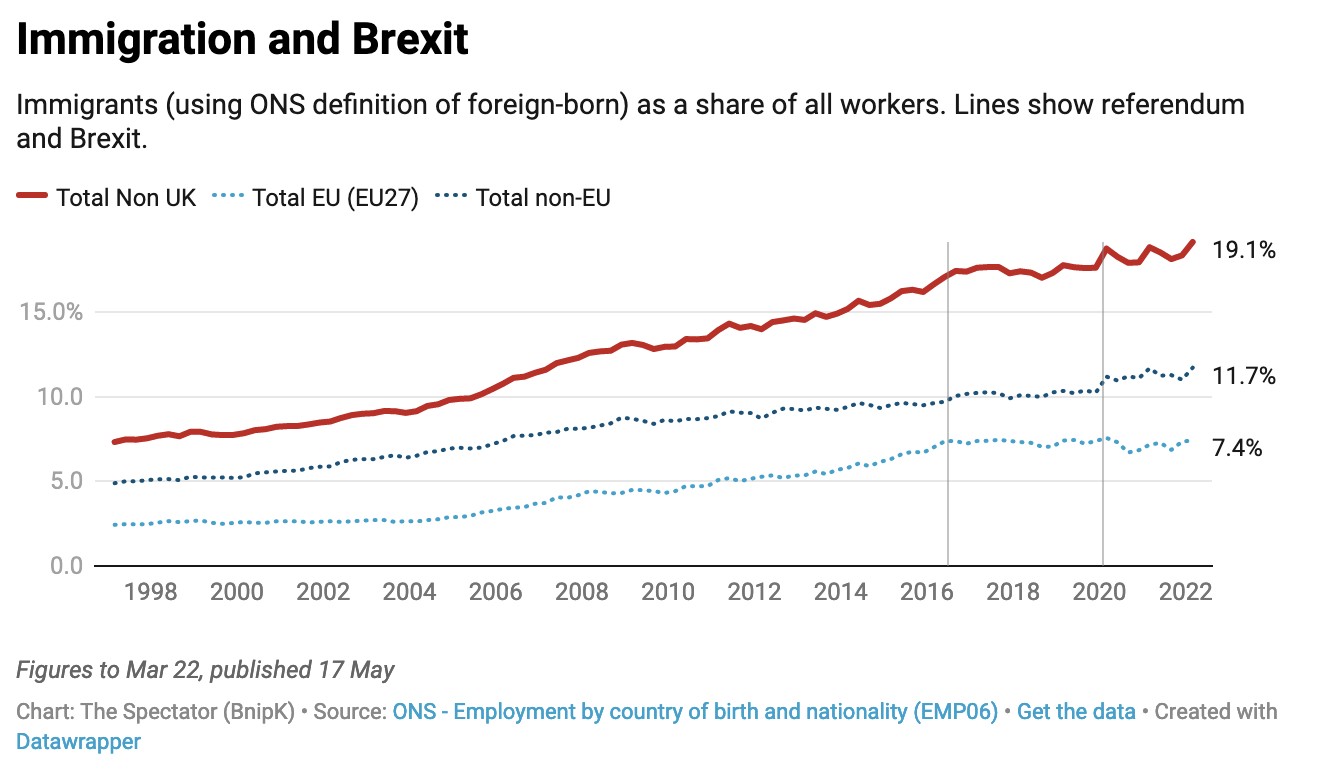

Brexit can’t be blamed for the worker shortage – immigrants now make up a record 19 per cent of the UK workforce.

‘Brexit has taken hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people out of the employment market and that undoubtedly is having an impact,’ says Steve Heapy, chief executive of holiday firm Jet2. You hear this quite a lot: during the fog of lockdown there were reports of EU nationals going home and not coming back. But ONS data points to an unbroken momentum of immigration (defined as foreign-born) rising from 7 per cent of the workforce when Blair came to power to 19 per cent now. A record high as a proportion, and also in absolute numbers. The inflow is now back to the old days. So no, Brexit did not take ‘hundreds of thousands, if not millions’ of out the labour market. As we shall see, lockdowns did.

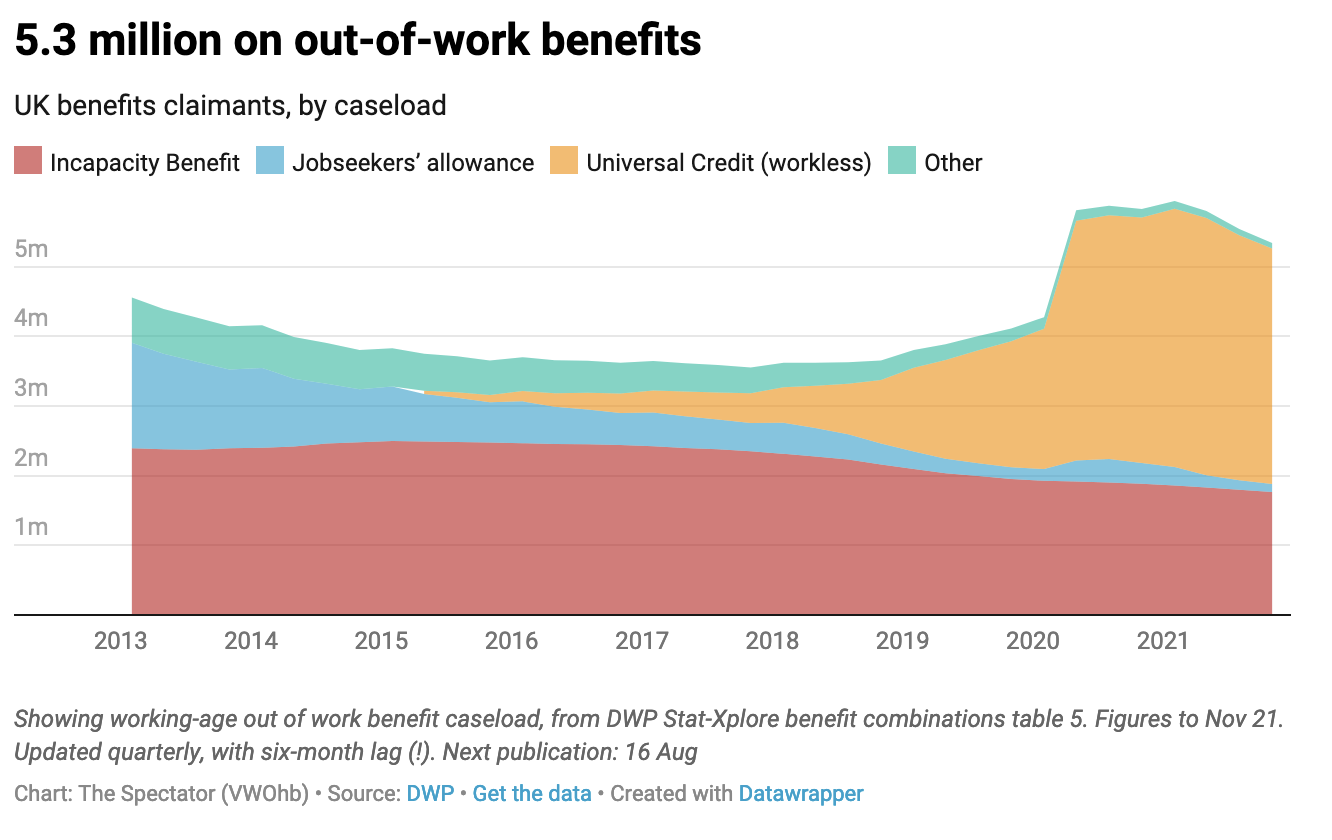

The DWP’s hidden total of those on out-of-work benefits.

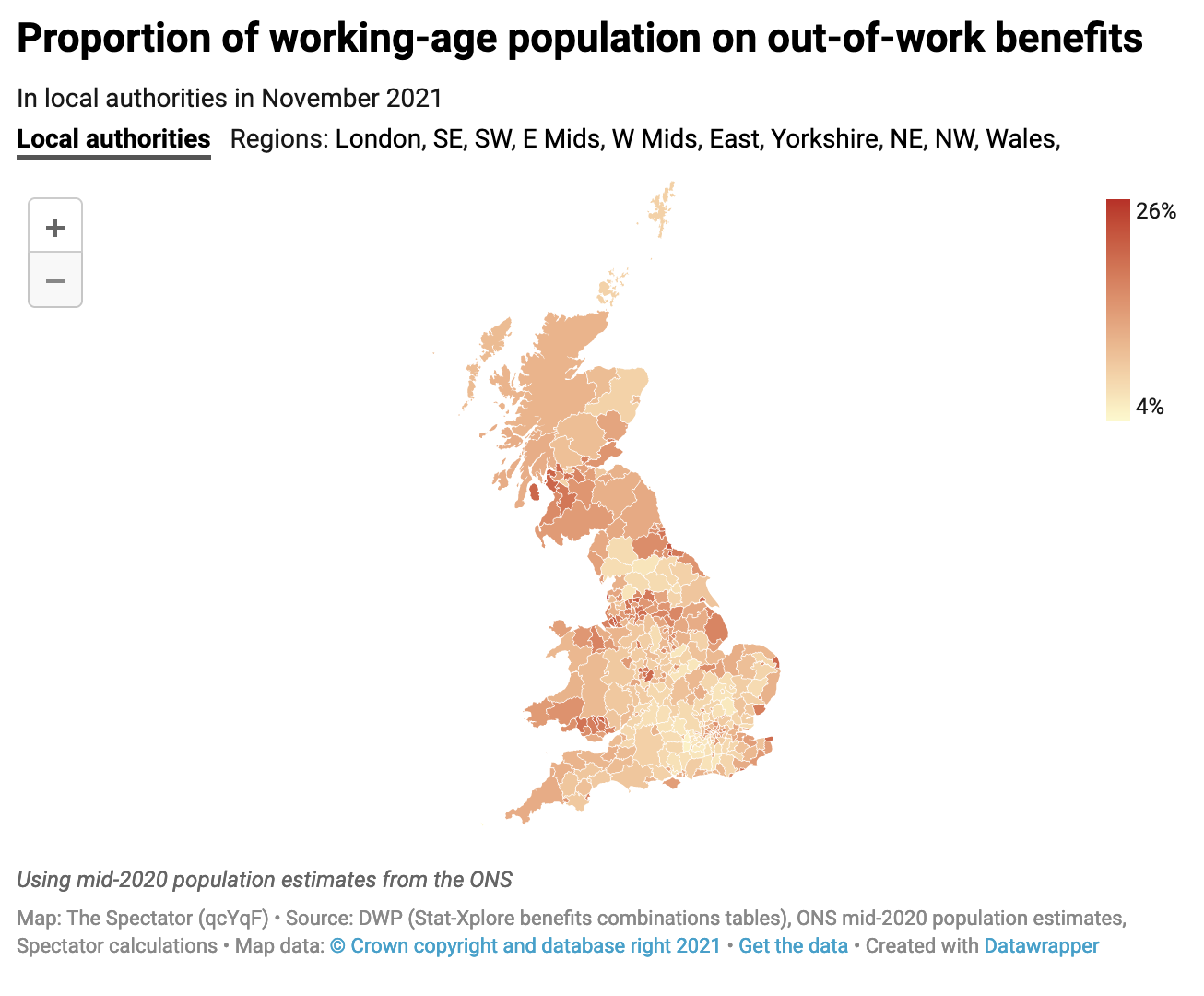

The below shows all ‘out-of-work’ benefits, as defined by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The figure stands at 5.33 million at the last count. This was the figure I didn’t believe, but we’ve had it checked out and according to recent DWP figures this is the total of all claiming what it describes as “out-of-work” benefits. That’s about one in nine Brits. Some 1.7 million are categorised as long-term sick (ie “incapacity benefit” and its successor schemes) – higher than the population of Estonia. Are we really saying there are 1.7 million people incapable of any work? Might these people have been written off too hastily, without more thought as to whether there is some role in our economy for them?

On top of that comes the jobless component of Universal Credit, which surged in lockdown but did not return. The DWP does not shout about the 5.33m figure: you have to work it out from the DWP StatXplore data labyrinth and they don’t make it easy. (In fact, its considerably harder to get a full picture of out-of-work benefits than it was 13 years ago under Labour – which goes against this government’s professed drive for transparency). Perhaps this is why the full story has not really come out yet: the full welfare story lies buried in a vault of data. So little attention is paid to this that there’s a six-month lag on the figures, so the below is for Nov21. It will have fallen by now – by not by much.

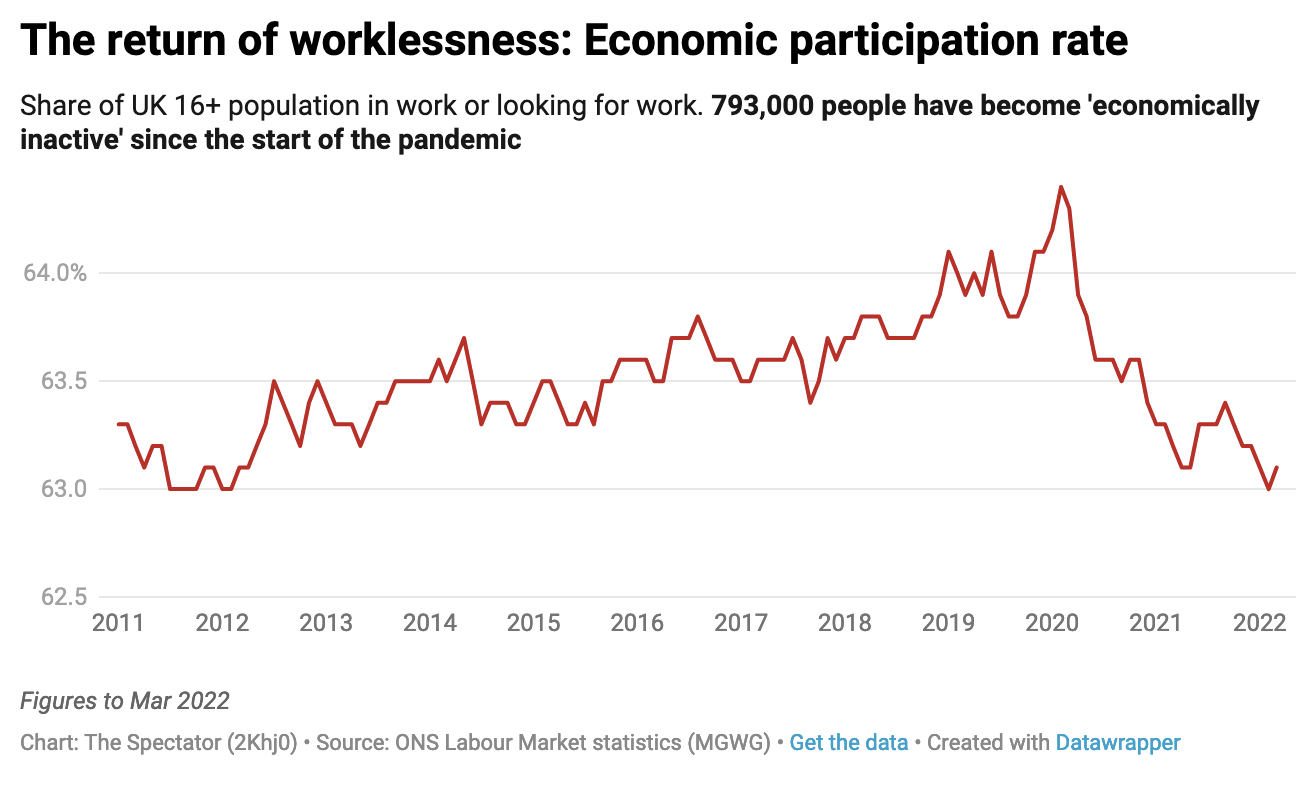

The UK labour force kept shrinking after the lockdowns.

The return of worklessness is exposed by ONS. This shows the proportion of over-16s who are not in work or looking for it. It takes in everything. As Capital Economics has pointed out: ‘the participation rate (the share of the working age population that is in or looking for work) is still, if anything, trending down. It is now at its lowest level since 2011.’

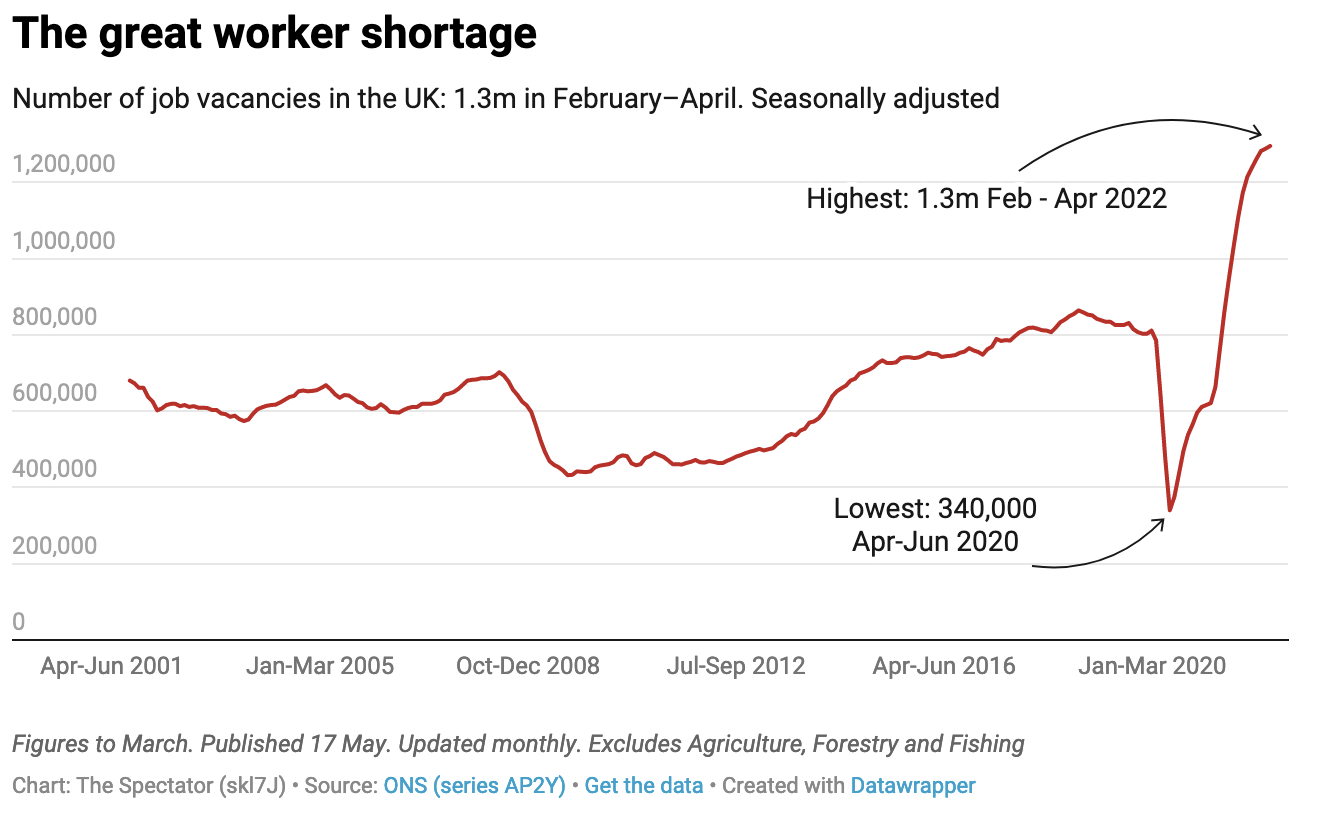

And meanwhile, there is a unprecedented number of vacancies.

Higher, by some margin, than the two decades before the pandemic. When Labour kept 5m on out-of-work benefits, there had been an economic crash. The Tories are doing it during the largest worker shortage in recorded history.

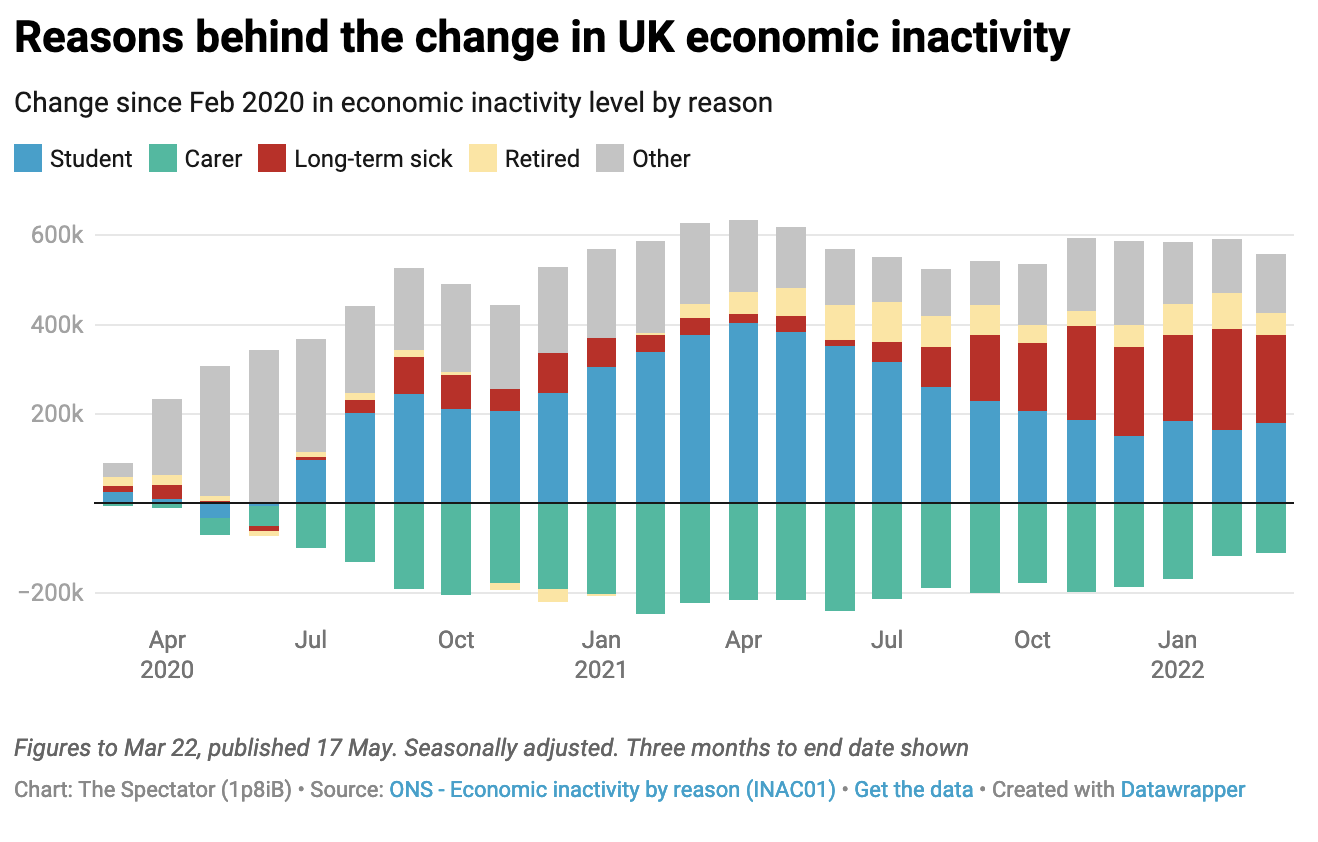

Early retirement – often cited as a post-lockdown factor – is a pretty small part of the story as the below ONS chart shows. Again, from Capital Economics: ‘The rise in inactivity in the UK over the past few months primarily reflects a rise in the number of long-term sick. The latter could reflect long COVID, though it is unclear why that would be affecting the UK more than other countries’. Quite. A subject worthy of further investigation.

Behind all too many of these statistics will be lives not being lived to their full potential, talents going to waste, communities wrecked by joblessness and children growing up in jobless households. This is not just a problem: Bevan had it right when he referred to the ‘giant evil’ of idleness. It’s what David Cameron dedicated his government to reducing. And it’s something that, if left undressed, will be one of the most pernicious side-effects of lockdown. I presented a Channel 4 documentary about this in 2014 and it’s odd to see the same problems emerge under the guys who promised to solve them last time. They can be solved again, but only if the government acts. And does far more than it’s doing now.

There has been a scheme launched to get half a million people off benefits by June, but this measure is flawed as it affects outflow – the problem is the overall (net) figure, that’s what should be targeted. And DWP systems struggle to keep count of how many people are on benefits: a sign that the system is being overwhelmed. The focus so far has been on those who say they are looking for work. But as the 2013 reforms found, it’s also necessary to look at those categorised as too sick to work. Is this always a fair categorisation? Might this be writing people off when they still have much to offer? Might it be better to assess them for what work they can do? Politically, this is difficult. But welfare reform is about saving lives, not saving money.

Therese Coffey has been pushing in Cabinet to bring back conditionality on welfare, to tighten the regulations. She deserves her colleagues’ support. The Tories used to own this agenda, having got it right before lockdown. Hundreds of thousands of people are now falling through the welfare net simply from lack of attention. To let welfare surge during a recession is bad. But to keep millions on benefits in the middle of the biggest worker shortage the economy has ever known is rather perverse – and politically indefensible. Especially when we have so much literatue showing the damage that worklessness inflicts. Moving from welfare to minimum-wage work gets an extra £6,000: so this, surely, is the most effective remedy to the cost-of-living crisis. With the UK having one of the highest minimum wages in the world and more vacancies than ever in our history, there might never be a better time to revive the welfare reform agenda.

PS The DWP StatExplore database does provide a tally for all on out-of-work benefits as a share of total in regions (and sub-regions) of the UK. With the caveats presented above (it’s data from November 2021, and about a third are long-term sick) here is how the national picture looks. Click on a region to dive deeper.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in