When the Victorian Whig historian, Lord Macaulay, touched on the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in his magisterial five-volume tome, The History of England (1848), he observed that “we cannot but be struck by its peculiar character”. With most people equating the very notion of “revolution” with radical change, Macaulay remarked that England’s Glorious Revolution had been a preserving revolution that restored the liberties of the English people by overthrowing the autocratic reign of James II. According to the Whig historian, the triumph of William III and Mary II had not only enhanced the constitutional powers of Parliament but heralded the “vindication of ancient rights”.

Macaulay’s interpretation of the Glorious Revolution had been shared by another Whig a century earlier, Edmund Burke, who proclaimed that “The Revolution was made to preserve our ancient indisputable laws and liberties”. Indeed the Whig statesman, who is perhaps remembered most for his strident opposition to the 1789 French Revolution, also commended another revolution for its preserving qualities. While the American Revolution eventually led to the severance of the American colonies from the British Crown, Burke saw it as restoring to the American insurgents, the traditional English liberties that had been trammelled by the autocratic tendencies of George III.

Just as Burke and Macaulay recognised the preserving revolutions of the past, tomorrow’s 500 year anniversary of the Protestant Reformation gives us occasion to remember one of the great preserving revolutions of human history.

With the dark days of sectarian rancour thankfully behind us, today’s Catholics and Protestants can rejoice in the faith they share in the teaching and redemptive work of Christ, together with a common affirmation of the Imago Dei, family life and rejection of atheistic secularism, but in the context of the 1500s, there is no doubt the Protestant dissenters saw themselves as embarking on a bold, restorative mission.

When an audacious thirty-three-year-old German monk reportedly nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Wittenburg Castle Church on 31 October 1517, Martin Luther (1483-1546) did not seek to overthrow the church but rather to draw it back to its Biblical roots. In what was primarily a list of grievances against the practices of the Roman Catholic Church in his day, Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses questioned the purchase of papal indulgences for the remission of sin. A tradition he saw not as a tenet of classical Christianity, but a piety concocted by the medieval church.

For the German firebrand who had rediscovered the treasuries of the Bible that he would later translate into the tongue of his countrymen and women, this practice flew in the face of the classic Christian doctrine that eternal redemption was not something to be earned, but a gift offered freely to all believers by the sacrificial death of Christ on the Cross. In calling the church to return to the simple teaching of scripture, Luther was joined on the continent by Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531) and John Calvin (1509-1564).

Although this push for renewal within the church inevitably led to a break with Rome and changed forever, the monolithic nature of Western Christendom with the emergence of new Protestant churches, Luther, Calvin, Zwingli and their followers were reluctant schismatics with no desire to create a new religion or even a radically new version of Christianity. On the contrary, these conservative revolutionaries saw themselves as seeking to restore the church to its original, New Testament form by peeling back the extra layers of dogma and praxis it had accreted since the early Middle Ages.

In their quest to recover the life of the early Church, the reformers stressed the importance of conforming the Church to what they regarded as the plain teachings of the Bible and thus repudiated the Papacy, the mass, the work of priestly mediation in the salvation of souls, the sale of indulgences, purgatory and other medieval-era Catholic doctrines and practices which they saw as extraneous innovations with no warrant from scripture.

While Catholics and Protestants will continue to debate the necessity and extent of such reforms, they now generally agree that the sixteenth-century church was in a state of spiritual decay with the need for many of its institutional abuses to be remedied. Accordingly, the basic aim of the reformers to bring restoration and renewal to the church of their day is widely affirmed.

As with the Glorious Revolution and American Revolution, however, the preserving revolution of the Reformation did not have the effect of turning back the clock on civilisation. By contrast, it acted as a catalyst for leading Europe and the West into the modern age. The doctrine of the “priesthood of all believers” introduced a radical egalitarianism that helped lay the foundation for modern democracy and human rights. Luther’s translation of the Bible into German advanced literacy rates and education in not only that country but other parts of Europe; and as Max Weber appreciated; the Calvinist-inspired work ethic unleashed the productive energy of nations, leading to industrialisation, free enterprise and the rise of modern capitalism.

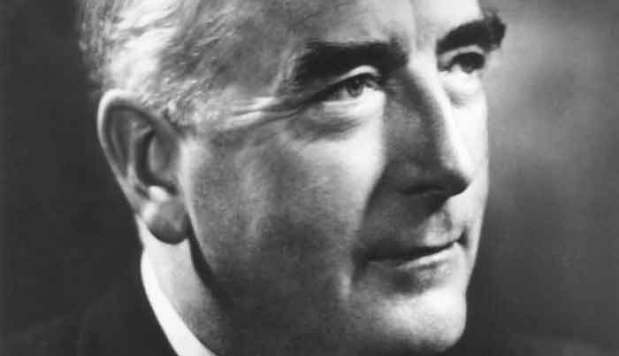

So while we remember a preserving revolution such as the Reformation 500 years ago, we celebrate it for not only restoring the best things of the past such as the Bible, which Sir Robert Menzies described in 1960 as “the most important thing in the world”, but for its contribution to modernity and human progress.

David Furse-Roberts is a Research Fellow at the Menzies Research Centre and editor of Menzies: The Forgotten Speeches, published by Connor Court.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in