With Australian politics becoming somewhat top-heavy with careerist party-hacks and apparatchiks who view power for its own sake as the endgame, 2017 saw the departure of two politicians whose contribution to public life was primarily driven by faith and its vision for human flourishing. Examples abound of such parliamentarians from all sides of Australian politics, but the following two cases are illustrative.

The first was a male Catholic of the centre-left from New South Wales, and the second, a female Protestant of the centre-right from Queensland. John Richard “Johno” Johnson, who died on 9 August, and Florence “Flo” Bjelke-Petersen, who left us this Wednesday, each in their own way personified and championed the spiritual impulses of their respective political traditions. In so doing, they not only leave our country all the richer but stand as magnetic poles that can serve to re-orientate the philosophical compass of both our major parties.

Earlier this year, the passing of the NSW Labor luminary, Johno Johnson, represented the loss of that ever-diminishing “cream of the working class” within the ALP. Born in Murwillumbah (NSW) in 1930 and educated at the local Catholic parish school, Johno worked in the family grocery store, the railways, the post office, the credit union and the Shop Assistants’ Union before finally assuming his seat in the NSW Legislative Council from 1976 to 2001. Never forgetting where he had come from, the former grocer embodied the uncomplicated lifestyle and values of the working people he represented.

The foremost of these traditional working-class values Johno embraced were, of course, those of family and faith. Married for over fifty-five years, he and his wife raised four adopted children. Like many in the Australian Labor Movement, Johnson was an unabashed Catholic, whom as Bob Carr observed, “helped to sustain the Catholic-Labor tradition into the modern age”. In that great Labor tradition of J H Scullin, Ben Chifley and Arthur Calwell, Johnno promulgated and practiced the Catholic social teachings of Pope Leo’s 1891 Encyclical, Rerum Novarum, with its emphasis on human dignity, community, family values, subsidiarity and the repudiation of atheistic communism.

At the same time as defending worker’s rights and advocating social justice for the poor and underprivileged, Johnno vigorously championed the traditional family, defended the rights of the unborn and opposed euthanasia. By channelling a Catholic social tradition that straddles both sides of the Australian political divide, Johnson earned respect from not only his own colleagues in the Labor Right but also from prominent Liberals such as Tony Abbott. Whilst his values may have invited derision from politically correct cultural elites, they held broad appeal to swathes of middle Australia schooled in common sense.

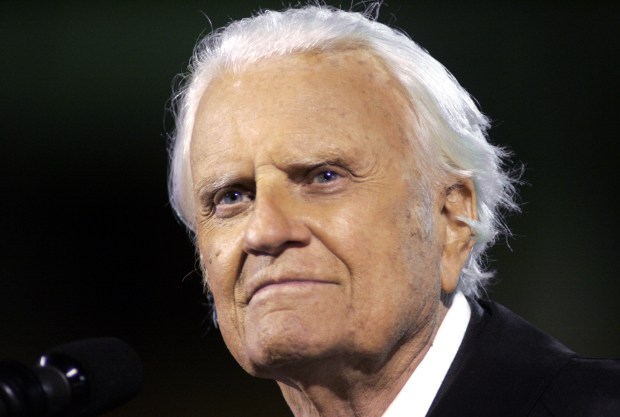

North of the NSW border and on the other side of the political fence, a comparable champion was to be found in Flo Bjelke-Petersen, a former National Party Senator for Queensland and wife of the long-serving Queensland Premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

Born as Florence Isabel Gilmour in Brisbane on 11 August 1920, Flo grew up in the riverside suburb of New Farm and was educated at Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School. Thereafter she worked as a receptionist for the Main Roads Commissioner and served as a Liberal Party member in Brisbane. In one of the visiting deputations to the Commissioner, she met Johannes Bjelke-Petersen whom she married at Fortitude Valley Presbyterian Church in May 1952. Enjoying fifty-three years of marriage, they raised their four children on Joh’s iconic Kingaroy property of “Bethany”.

As well as being the wife of Sir Joh, Flo enjoyed a distinguished political career in her own right, serving as a Nationals Senator for Queensland from 1981 to 1993. Acquiring a reputation as a loyal advocate for her home state of Queensland, Senator Bjelke-Petersen also publicly shared her faith in Jesus Christ and emerged as a champion of traditional moral values. Like Johnson, she appreciated the inestimable social capital of family, holding that “families are the cornerstone of society”. Committed to preserving the dignity of human life, she was vocal about the dangers of pornography and abortion on demand.

Like that other great matriarch of Australian conservative politics, Dame Pattie Menzies, Flo hailed from Presbyterian stock and brought the Calvinist virtues of personal propriety, integrity, hard-work and family to bear on her public and professional life. While rightfully recognising that the Coalition parties have always been secular institutions open to people of all faiths and none, Flo nonetheless helped to sustain the strong Protestant tradition in the Australian centre-right with its historic emphases on freedom of conscience, thrift, gainful enterprise, volunteerism, domestic sobriety and loyalty to the Crown; a tradition documented by Judith Brett in her volume, Australian Liberals and the Moral Middle Class (2003).

Australia is a secular democracy but one nourished by a rich Judeo-Christian heritage. Accordingly, it is a historical reality that the philosophies of Australia’s two major parties each draw deeply from the Catholic and Protestant tributaries of Christianity. As the Australian historian Dr Meredith Lake points out, “the foundations of both major political parties are shaped significantly by the Bible”. In our age of dogmatic secularism, the lives and legacies of both Johnson and Bjelke-Petersen are salutary reminders of this. Although our political parties must remain open to all citizens, Robert Menzies reminded us in 1959 that “there is room in every political party for Christian men and women of all schools of Christian thought”.

Just like the humble Sydney grocer and the Queensland queen of pumpkin scones, people of faith must continue to engage in politics, not so much to “impose” their values but to keep alive the very spiritual traditions that gave fire to our democracy. At a time when political movements in Australia and overseas are either consumed by internal squabbling, beholden to sectionalism or gripped by the fever of populism, party activists could do worse than walk in the footsteps of figures like Johnson and Bjelke-Petersen who remained true to the founding creed of their parties.

David Furse-Roberts is a Research Fellow at the Menzies Research Centre and is editing a volume of speeches by former Prime Minister John Howard to be released in early 2018.

Illustration: Facebook.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in