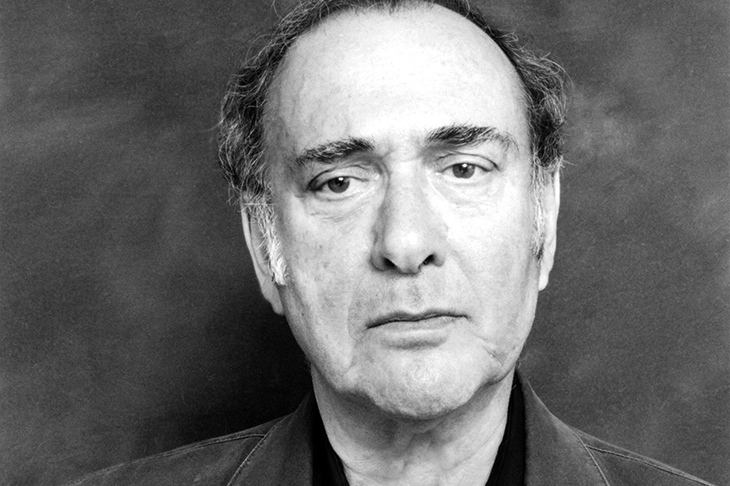

I think everyone was a little nervous of Harold. Including Harold, sometimes. He was affable, warm, generous, impulsive — and unpredictable. Like his plays, where the hyper-banal surfaces — the synthetic memories and false nostalgia of Old Times, the aural drivel of Rose in The Room, the bogus familial warmth of The Homecoming — are fragile and about to be displaced by something ugly and authentic, something obscure and violent. Plays where on countless occasions — think of Lenny in The Homecoming or the alcoholic Hirst in No Man’s Land — a speech will take off into dramatic Tourette’s, unstoppable and at the edge of sense. The plays are edgy, alert to something sinister at the periphery. Harold once described his plays as being about the weasel under the cocktail cabinet. Later, he repudiated this description. In fact, it is the perfect encapsulation, but no one likes to be fixed in a formulated phrase — particularly a phrase of one’s own coinage. The plays are unstable, never more dangerous than when the surface of the dialogue is at its emptiest: think of One for the Road, with its grotesque affability — signalled by the title’s pub-speak — and its pragmatic, morally drained, unexcitable sadism.

‘Style’, wrote Buffon, ‘c’est l’homme.’ With Harold, it was as well to be aware that the weasel wasn’t confined to the drama. It might draw blood on the domestic stage. He was all about surprise and social suspense.

I first met him in Claire Tomalin’s basement kitchen in Gloucester Crescent at an impromptu party. Claire was the literary editor of the New Statesman. I was her summer stand-in theatre critic (while Benedict Nightingale was having his annual fortnight’s holiday) and I had reviewed No Man’s Land, with Gielgud as Spooner and Ralph Richardson as Hirst. Harold thanked me for the review. I was emboldened and explained that I’d had two putative interpretations — both wrong, I now think — but not enough space (800 words) adequately to ventilate the two takes on his play. He looked at me quizzically, almost boyishly, his eyes smiling. ‘How can I help you?’ he said. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘I was wondering if I was right.’ He stopped smiling, reached into the inside pocket of his jacket, and took out a spectacle case. Opening it, he put on a pair of dark glasses and looked at me, enigmatically, eyelessly. After a pause: ‘Search me, squire.’

Harold was wedded to the world of little magazines — including my own Areté. What was that about? It was partly superstitious appeasement, I think. Harold remembered his beginnings, his first poems in Tambimuttu’s Poetry London. (He was often pissed off, but he was never grand or pompous. His favoured formula for praise was ‘bloody good’, either in block capitals or booming actor’s baritone.) And it was partly sentimental nostalgia for the camaraderie of failure, and partly a specific piety about poetry, which for him was the heart of the little magazine.

The next time I met Harold was at a bleak party in Ian Hamilton’s mean office (I was reviews editor at Hamilton’s The New Review). Xandra Gowrie saw me standing on my own and introduced me to Harold. ‘Actually,’ I said, ‘Harold and I have already met.’ In the interval, I had reviewed Harold’s Poems and Prose 1949–1977 — scathingly amused in tone. Without taking his eyes off me, he took a drink. ‘Only once.’ He took another drink. It wasn’t quite ‘fuck off’ but it was a near thing. And beautifully delivered.

At another party I was standing next to my old boss at Faber, Matthew Evans. ‘Good night for the Raine family,’ he said with his irresistible grin. ‘I’m just going to say hello to Harold.’

He was back in 30 seconds, grin gone. ‘What a fucker.’

‘What happened?’

‘I said, “Hello, Harold. How are you?” And he said, “Fuck off. I sent you my new play [Celebration] a week ago and you haven’t said what you think, whether you liked it. You’re supposed to be my publisher. Fuck off.”’

You didn’t want to get on the wrong side of Harold. When I still worked at Faber, sometime in the late 1980s, a confrère of his rang to ask if I would publish their joint translations of the Nicaraguan poet and politician Ernesto Cardenal. The intermediary on the phone would do the translations, Harold would ‘add the poetry’. I said that I’d be pleased to consider the translations when they had been done. (Actually, I had heard Cardenal read in India and I had not been impressed.) But that wasn’t the question: the question was, would I agree in advance to publish the poems? I said I couldn’t do that, but I would be very pleased to… etc. My interlocutor lost his temper, appealed to Harold’s reputation, but I was firm. He was equally firm. They wouldn’t undertake the work without a guarantee of publication. Which I wouldn’t give.

I then read the New Directions two-volume Poems of Ernesto Cardenal, translated by Alastair Reid. I thought they were no good, but I read on very carefully — knowing that one day I might find myself in an argument with Harold. I wanted to acquit myself as well as possible in what might be a noisy, public viva voce. For about a year, whenever the firm threw a party, I scanned the guest list — and if Harold had accepted, I strategically absented myself. Perhaps unnecessarily. Perhaps not. It depended on whether Harold had had a drink, and how much.

Touching Harold… At the first night of Celebration at the Almeida, just before the performance, without thinking, I kissed him on both cheeks. A mistake. Unmistakably, though he was affable still. There wasn’t a trace of the luvvie in him. When the performance was over, he was standing in the court of the Almeida, receiving congratulations, holding court. I said that he must be tired. ‘What the fuck do you mean?’ Weeks of rehearsal, I began, the strain of a first night. He cut me off. ‘Astonishing what stupid things people say. Of course I’m not tired. I’m going off now to have dinner with Antonia.’ At which point, I was rescued by an old friend of Harold’s, who asked him to go into the bar to meet his new wife. ‘Bring her out here.’

At the first night of Moonlight, I asked him before the performance how he was feeling. ‘Bloody nervous, I don’t mind telling you.’ The nervous side co-existed with the brusque, dismissive side and it was very endearing. I saw it once on television, when he did a Face to Face with Jeremy Isaacs. I think he was spooked by the singular conditions of the programme — no prior sight of the questions, no prior discussion, in fact no meeting with the interviewer before the interview. Isaacs’s second question was really a statement: of course, he said, you’ve read Wittgenstein. It was enough to panic Harold, the possibility of a public viva on Wittgenstein.

He was very generous to Areté — giving the magazine a little play, poems, prose poems, a letter written about Waiting for Godot when he was still a jobbing actor, a sizable chunk of his screenplay for Lolita. More than that, he was enthusiastic about the work of other writers which appeared in the magazine. In issue one, there was a little sketch by Patrick Marber. Harold left a number on my answer machine. I rang him back. ‘Bloody funny play by Patrick Marber [Casting]. I read it to Antonia. Did all the parts. Bloody funny. Well done.’

When Areté decided to give a 10th anniversary party for contributors, Frances Stonor Saunders telephoned Harold to see if he could come. Phew. She then rang me, in a state of shock. ‘THIS IS A PRIVATE NUMBER. HOW DID YOU GET THIS NUMBER?’ A tirade. ‘It’s nothing,’ I said. ‘It’s Harold. I’ll email him. Don’t worry.’

‘Dear Harold,’ I wrote. ‘I hear you turned your Flammenwerfer on my editorial assistant, the delightful Frances Stonor Saunders — whom you’ve met, and liked, in other circumstances. It really wasn’t her fault that she rang your private number. It was in my address book — because you gave it to me, twice, without saying it was Top Secret… Anyway, I think being scorched by you is one of life’s central experiences —from which Fran will benefit in due course.’ A couple of nervous days passed. Then Harold emailed an explanation and an apology and an acceptance.

In T.S. Eliot’s essay on Hamlet, we find the following crucial passage. It explains a lot about Harold and the connection between the writer and the man, why they were of a piece. ‘The intense feeling, ecstatic or terrible, without an object or exceeding its object, is something which every person of sensibility has known; it is doubtless a subject of study for pathologists. It often occurs in adolescence: the ordinary person puts these feelings to sleep, or trims down his feeling to fit the business world; the artist keeps it alive by his ability to intensify the world to his emotions [my italics].’

We all know what it is like to lose our temper — sometimes about very small things; especially small things — but mostly we control it. Harold was incapable of tailoring his feelings to fit the social world. He wasn’t a trimmer. That was the price we sometimes paid for the art — willingly.

He was one of life’s central experiences — Flammenwerfer and all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in