Who was Frans Hals? We know very little about him. He was baptised in either 1582 or 1583 in Antwerp. He died in 1666 at the age of 83 or 84. Approximately 220 works survive. One discredited narrative claimed Hals was a drunk – an inference probably based on his subject matter. There are several depictions of drinkers. On the other hand, there is his evident industry. Two streets in Haarlem, where he lived his entire life, have been identified, but not the actual houses. He was buried in St Bavo’s church in the Grote Markt, which was originally Catholic but became Protestant. There are two commemorative slabs next to each other in the chancel floor competing for authenticity. Which is appropriate, because there are two Frans Hals – the traditionalist and the innovator. They co-exist.

The Frans Hals revered (and sometimes lovingly, painstakingly copied) by Whistler, John Singer Sargent, Lovis Corinth, James Ensor and Van Gogh is a spontaneous, apparently improvisatory painter. Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: ‘What struck me most on seeing the old Dutch pictures again is that most of them were painted quickly, that these great masters, such as a Frans Hals, a Rembrandt, a Ruysdael and so many others – dashed off a thing from the first stroke and did not retouch it so very much…’ You can see this painter’s signature style – almost a kind of unhesitating writing, full-tilt, semi-automatic – in the Rijksmuseum’s ‘Militia Man’ (c.1629) also known as ‘Merry Drinker’ (see below). His left radically foreshortened arm is holding out a glass to the viewer. The beard and moustache are wind-swept and warped like a coastal thorn tree, detailed without being pedantic, precise yet with an air of being tossed off. The fastening on his bodice: three or four faint red slashes with the temporary status of shaving cuts, but doing the job.

In the next-door room, there is a ‘Portrait of Lucas de Clerq’ (1635). The sitter’s double chin is visible under his Van Dyck beard. One chamois glove emerges from the sling of his black satin cloak. It is meticulous and wooden. The traditional method is all about conclusion and finish – a bit like Omar Sharif in David Lean’s film of Doctor Zhivago, which had Sharif in bed with Julie Christie as if both had just been to the hairdresser’s. His vinyl hair kempt as a beetle’s wing case. Bed hair it wasn’t. The other Hals is all about process and the exactitude of accident. Tony Lock, the England spinner, allegedly caught a swallow as he was daydreaming in the slips – a brilliant accident. Hals, at his best, was the Papageno of painting, catching bird after bird, effects on the wing.

This Hals never allows you to forget that you’re looking at a painting. You are, as it were, given the painter’s working. So you can see how brilliantly it is done, so you can appreciate the brilliant equivalences. The other Hals, the traditionalist, isn’t without merit either. ‘Portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste’ (1635), in the Rijksmuseum, is a meticulous rendering of ruff, of the 14 covered buttons on her cuff etc., but quietly remarkable for the direct gaze of the sitter and the perfectly captured wary mouth. In its way, this is as effective as the Rijksmuseum’s ‘Portrait of a Man’ (c.1635) which is ostensibly freer in its treatment, especially of the sitter’s Boris Johnson hair.

The last large exhibition of Hals was in 1989 at Washington, the Royal Academy and the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem. Somehow, though, the reputation of Hals as one of the great painters, the equal, say, of Rembrandt, hasn’t been securely established and it is worth asking why. In essence, Hals is a portraitist – but one who specialises in the group portrait. There is a whole room of the Frans Hals Museum given over to large canvases depicting various militias. It is telling how frequently these are reproduced as details, rather than the full cinemascope. Each militia man paid 60 guilders, so the pragmatic compositional choice, not uniformly resisted, is liable to be the identity parade. Hals succumbs only in his last painting of the St George militia (1639). Otherwise, he does his level best to disguise and diversify. Admittedly, there are a number of hands that have to be assigned to their owners. And sometimes the gestures are coarse, big as gestures in ballet, for example the downward open palm that indicates speech and conversation. Take ‘Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company’ (1627) with its poorly painted crab and its plate of oysters (easily mistaken for fried eggs). Everyone is exaggeratedly laid back – group-think of determinedly unposed posing. But the differentiation of faces is terrific and unforced, as it is in the other group paintings.

In ‘Banquet of the officers of the Caliver-men Civic Guard’ (1627), as well as a nice dog, bottom left, there is a figure at the top of the painting pouring the contents of his glass into another person’s glass. His sceptical expression is mild but exact and accurate. About two notches down from Dickens’s butler in Our Mutual Friend, who is called the Analytical Chemist, the soubriquet an index of his opinion of the wine he is serving. In the same painting, bottom left, is a grumpy person with an expression of repressed indignation. On the right, there is a bald man with perfect bags under his eyes. But you have to pick out these accuracies from the plethora, from the ambient noise.

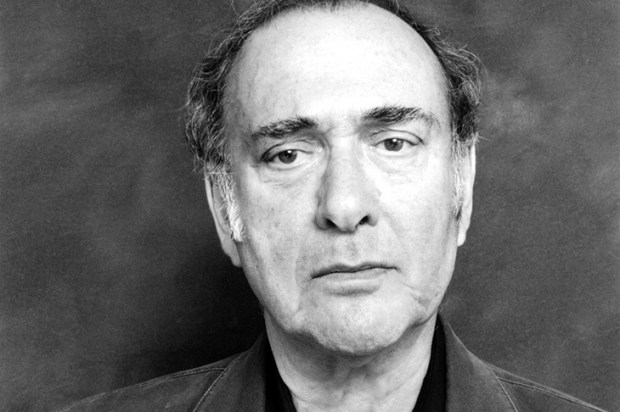

In the Frans Hals Museum, I saw the restoration under way of yet another group painting of the St George militia (1616). At its centre, looking out, was George Osborne in full historical fancy dress, with what the Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell called Osborne’s bum-nose. (Alan Bennett, on a writers’ trip to Moscow, amused us all by affecting to see Melvyn Bragg everywhere, including the chorus of the Bolshoi. It was plausible more often than you might think. The human face is only as various as a pack of cards: recurrence is to be expected. Hals’s ‘Portrait of Jacobus Hendriksz Zaffius’, 1611, has a bent nose, slewed mouth and the neat Astroturf beard of the former Labour secretary of state, Frank Dobson.) The Osborne figure is in a standard pose: hand on waist, palm displayed, elbow out to the viewer. You can see this trope everywhere, including the Rijksmuseum’s ‘Standard Bearer’ by Rembrandt. Lenin is in the mix. (Compare Verdi, aka Johan Claesz van Loo, third left at the bottom of ‘The Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1639’.)

Three things impressed me in addition to the portraiture – of, for instance, a man on the right, raising a quizzical eyebrow – and they were thoughtful incidentals. The white damask tablecloth was a bravura passage of precise textural rendering. The legs of the figure on the bottom left of the painting were pushing against the tablecloth, taking its hang out of true. But the genius was the cushion the figure was sitting on. It is slightly too big for the seat of the chair and has worked forward so there is a sag, a slub, an overhang. A nothing, an unimportant observation, but all the same a little miracle of attention. The eye in love with the world, in thrall to every detail belonging to the beloved.

Hals’s ‘The Meagre Company’ is another group portrait, completed by Pieter Codde, when Hals found rental accommodation in Amsterdam too expensive – a rare biographical detail preserved by the surviving correspondence with legal notaries. The patron depicted on the left – Spike Milligan – is notable not just for his face but also for his legs. You have to look carefully to see their brilliant naturalness, especially his left leg tucked away at an angle behind him. It is the way people sit. So are the crossed ankles of the person to his right. It is these unconsidered trifles that constitute great art – once they have been seen and set down by the painter, where they wait for us to discover them for ourselves. These tiny shocks of recognition.

In the restoration studio of the Rijksmuseum, I saw a ‘Portrait of a Man’ (c.1658) which is painted with a limited palette on a wooden panel. It is a contemporary face with a slightly Bourbon lower lip, a lip with cleavage. Unforgettable. And there is the shadow cast by his moustache – a trick Hals repeats more than once. But the lip is unique.

Which brings us to the other reason Hals is undervalued. He is famous for his flamboyant laughing faces, particularly of children, executed with unabashed freedom. ‘Laughing Boy’ (c.1620-5) in the Mauritshuis in The Hague is a marvel. But it is a marvel, a discovery, that is repeated and repeated. The spontaneous becomes habitual – unlike that one-off Bourbon lower lip like a tiger prawn. Unlike Vermeer who never repeated himself. Or, if he did, historical accident, the winnowing of time, has conferred rarity. Hals is in the same danger as Murillo, typecast as the painter of ragamuffin children. You need variety of subject to be a great painter.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in