By 1930, Pablo Picasso, nearing 50, was as rich as Croesus. He was the occupant of a flat and studio in rue La Boétie, in the ritzy 8th arrondissement, owner of a country mansion in the north-west, towards Normandy, and was chauffeured around in an adored Hispano-Suiza. He stored the thousands of French francs from the sale of his work in sacks deep inside a Banque de France vault, like a ‘country bumpkin who keeps his savings sewn into his mattress’, someone once said.

Married since 1918 to one of Sergei Diaghilev’s ballerinas, Olga Khokhlova, Picasso was coming to dominate the art world in a manner no painter has before or since — including, increasingly and importantly, New York. But by mid-1931, he had worries. After the pioneering profligacy of his cubist period some 15 years before, followed by the gigantist neoclassical works of the 1920s, he had begun to sculpt — as a hobby, really — and was no longer painting with quite the verve and daring of his twenties and thirties.

This, of course, is relative. An astounding ‘Crucifixion’ of February 1930 and his jagged ‘Seated Bather’ from later that year are, by any standards, masterpieces. But he was, in his own mind, in hiatus. Picasso was pursued throughout his long life by a pathological dread of death, specifically of dying before he had created what he considered a proper legacy.

It was the Picasso paradox: turning 40 in 1921, his fame and earning power were assured and growing. Yet as the 1920s wore on he became highly acquisitive, a hoarder, terrified of not doing enough and being returned to the abject poverty he’d suffered in his early Paris years.

In 1930, moreover, his mother had been robbed in Barcelona of 400 of her son’s artworks, a miserable episode that would drag on for eight years, and which saw Picasso frequently attacked for self-publicity and for keeping his mother in penury (he didn’t). His wife Olga, meanwhile, was sliding into mental decline, her marriage to the demonic, dismembering artist characterised from the mid-1920s by rows and hysteria, her physical health undermined by frequent gynaecological haemorrhaging.

As his sixth decade approached, something flipped in Picasso. He would stop at nothing either to renew himself or get richer. The signal public event of 1932, the year being celebrated at a monumental Picasso exhibition at Tate Modern — an expanded version of a recent four-month hang at Paris’s Musée Picasso — was the first major show of his career.

‘Why,’ Picasso was reported as saying in mid-June of that year, ‘should I deny myself the joy of seeing once again everything that I produced over a third of a century? So here I am, reinvigorated and full of life, taking care of an exhibition of my works for the first time [at Paris’s Galeries Georges Petit], like a lad of 20. It feels as if I’m witnessing a retrospective vision of myself ten years after my death.’

Reinvigorated and full of life he certainly was. An unslakeable thirst for work lies behind Picasso 1932 — Love, Fame, Tragedy. Along with numerous drawings, prints and bits of sculpture, he produced 64 individual paintings in his 51st year. He knew his worth. Three months into 1932, a 1906 canvas, ‘La Coiffure’, sold in Paris for a then record 56,000 francs (£200,000 today). (By the mid-1930s, the vast wads of cash in the bank vault required more than one strongroom.) The milestone birthday on 25 October 1931 released in him energies that would have been startling enough in a lad of 20.

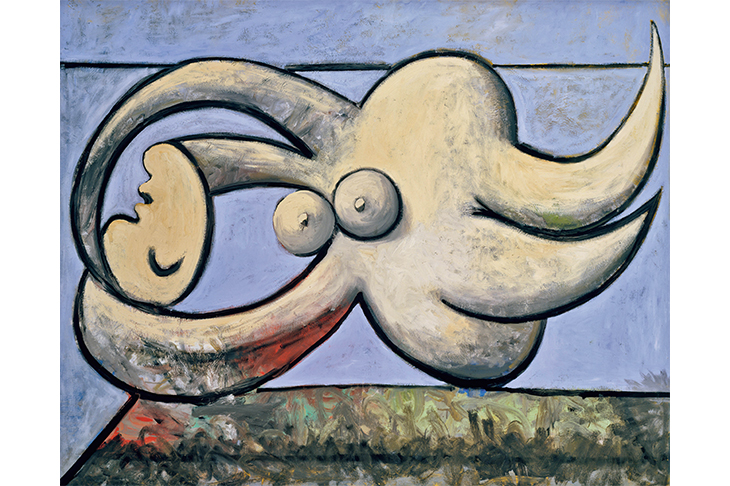

Here, right from the start of 1932, are serene, voluptuous portraits of a woman sleeping, resting, reading and dreaming. With a phallic brush, Picasso obsesses repeatedly over a classical Greek-like female head; sensual, octopoid, with frond-like limbs; spherical breasts and enfolding vaginal apertures — to say nothing of bulbous penile rods and shafts. The oneiric images are set sometimes on a beach but most often in an interior. In the frame there is frequently a mirror, an armchair, a plant. Most of the pictures pulsate with sexual adventure and bodily contentment. One, ‘Bather with Beach Ball’, shows the same woman as a kind of pneumatic angel, reaching athletically for the moon. It’s one of the seminal oil paintings of the 1930s. All are probing, radiant works.

What of sex? Tellingly, the Musée Picasso show’s subtitle was ‘Année érotique’. At the start of 1927 the then 45-year-old artist had spotted the blonde 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter in a Paris street. He simply picked her up and announced they were going to do ‘great things together’. She’d never heard of him, so to convince her Picasso marched her to a bookshop where various volumes about him proved that he was a famous artist. Five years later she had become his regular model, muse and mistress. She lies plumb at the heart of the Andalusian’s 1932.

Outwardly, he and Olga lived a life of conjugal parity. In Paris they attended opera premières and concerts, though not, interestingly, the vernissage on 16 June of Picasso’s first retrospective. It’s probable that the shock for his wife of being confronted by so many concupiscent images of Walter would have caused ‘an ugly scene’ claims Picasso’s biographer John Richardson. It’s also likely that Olga knew about the girl by that point. For their assignations in Paris, painterly and sexual, Picasso had rented a Left Bank flat. He also had her stay frequently — when Olga was absent — at the unheated country mansion, Boisgeloup. There, plump and formally dressed, Picasso behaved with his family ‘like a quintessential bourgeois husband and father’, Richardson writes, ‘the antithesis of the priapic polymorph he would turn back into, after his wife and child returned to Paris’.

He was also chasing girls in Paris. It was a habit from his promiscuous youth: another of his weapons, now, against death. Little about the girls in question is known, though one was a Japanese model, of whom two portraits were made in the summer of 1932. Olga put an end to the affair, something she never attempted with Walter. Picasso was insatiable. In company, Richardson observed, ‘everyone had to be seduced’ by him. ‘He’d imbibe all that stolen energy and stride off into the studio and work all night. I can’t imagine the hell of being married to him!’

It wasn’t all sex for the 50-year-old, though there was clearly lots of it, matched only by the unremitting pace of work. Darkness descended at year’s end, when Picasso produced the most astonishing series of prints and drawings of the crucifixion, inspired by Grünewald’s late 15th-century ‘Isenheim Altarpiece’. These clattering, boney pictures cover substantial wall space at Tate Modern and seem to stand as a corrective to the lush sensuality that has gone before. Picasso sensed that every carnal pleasure is inevitably, existentially, followed by mortal pain. Everything must end; this he painted throughout his career.

The ‘tragedy’ of Tate Modern’s title refers in part to Walter losing her beautiful tresses in late autumn 1932 after swimming, or possibly kayaking, in the Marne. She caught a spirochetal infection from rats in the river. For Picasso, who produced a number of haunted pictures of his girlfriend being saved from the water, this too was an end. A spell was broken. Nonetheless, within two years she was pregnant by him. A girl, Maya, was born in September 1935 (and is still with us). Picasso then took a new lover: Dora Maar.

Shrewdly, Tate Modern has mounted a detailed show that displays this half-man half-monster at a creative zenith. Picasso was drawing on his brilliant past while laying foundations for an even more extraordinary future. His 20th-century masterpiece ‘Guernica’ lay five years away. But as picture after picture at Tate Modern shows, Picasso at 50 felt younger than ever; and, one might add, hornier.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in