ENO’s new production of Wagner’s The Mastersingers of Nuremberg is a triumph about which only the most niggling of reservations can be set. Every aspect — orchestral, vocal, production — works in harmony to effect one of the richest, most intensely absorbing, energising and delightful afternoons and evenings I have ever spent in the theatre. It is above all a team effort, and since individuality and teamwork are very much what Mastersingers is about, that made it still more satisfying.

However, two people must be singled out: Richard Jones for the finest of all the productions of his I’ve seen. This one comes from Cardiff, where it was unveiled almost five years ago. The set designs remain the same: a stark Act I, a stylised and cute, though overlit, Act II, and a super-realistic first half of Act III, Sachs’s workshop. The acting is remarkable, on everyone’s part: there are a few new touches, most of which I could do without. To have Beckmesser using a throat-spray and then inhaling over a bowl with a towel over his head, just before his attempt at the Prize Song, is absurd; but to have him naked at the end of Act II, only his smashed lute preserving his modesty, is both funny and heartbreaking. None of the opera’s pathos or humour is overlooked, almost nothing is underlined.

The other ‘star’ is Edward Gardner, astonishingly conducting his first Master-singers and instantly demanding a place among master conductors: he should be knighted forthwith. The ebb and flow which made five hours seem like two is something that only a tiny handful of conductors of this extremely tricky work have managed to such inconspicuous effect. There is no false economy: the Prelude was played for all it was worth, and all the mini-climaxes received their due, while the stunning peaks of the work — the riot at the end of Act II (though not well staged — it never is), the supremely confident Quintet, the ‘Awake!’ chorus —made a far fuller effect than they ever can in Bayreuth, with its recessed orchestral sound.

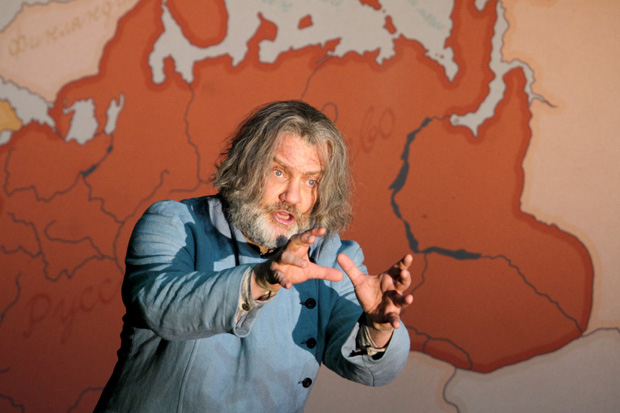

All the solo singers are admirable; none of them stands out. This was Iain Paterson’s first Sachs, and though he didn’t tire in this longest of all operatic roles, and has the right ideas about the heights and depths (he regards Sachs as virtually bipolar, a mistake), he will deepen his understanding; and his two great monologues are already fine. Andrew Shore’s Beckmesser is immaculate, a serious portrayal in the welcome modern mode. The greatest relief for me is that both the young lovers, who to judge from many recent performances are the most difficult to cast, are thrilling: the hefty tenor — about a third the size of Johan Botha — Gwyn Hughes Jones portrays Walter as a natural rebel, ill-clad and not well-mannered, but he sings gloriously; for once the Prize Song grows as it should from Sachs’s study to the festival meadow. In the Eva of Rachel Nicholls he meets a singer who for once has a voice to match his, and in her tantrums sounds like the Brünnhilde she has already sung. But why does she wander off-stage for his Prize Song? Her father, Pogner, is James Creswell, wonderfully full-voiced and moving.

At the end, instead of the injunction to ‘honour your German masters’ we have ‘noble masters’, while the crowd holds up pictures of the many great German geniuses there have been over the centuries. That is feeble. Anyone in search of the alleged ‘dark underside’ of this glowing masterpiece — and there are people who make a career, as academics or critics, claiming that it contributed to the rise of the wrong kind of German nationalism (or if it didn’t, it should have done) — won’t find a hint of it in this production of what after all is one of the grandest and most moving examples of holy German art.

Two evenings earlier I had gone to the Royal Opera’s revival of Tim Albery’s production of Der fliegende Holländer, performed in its original Dresden version, without the ‘Redemption’ theme at the end of the Overture and of the opera, and done straight through without an interval. Those are all good things, since the momentum generated at the end of the first two acts is fatally dissipated if there are intervals. But I found it, even so, a lacklustre evening. Andris Nelsons is a fine conductor of romantic scores, but here the only thrilling passage was the very opening of the Overture. The rest of it might well have been called ‘Smooth Journey and Pleasant Voyage’. The casting is strong, but compared with the towering account of the title role he gave with the Zurich Opera at the Festival Hall in 2012 — a concert performance — Bryn Terfel’s Dutchman here seemed mainly just depressed. Adrianne Pieczonka is his would-be saviour, who first appears — far too soon — during his monologue, nursing a model galleon; at the end of the opera she simply expires and collapses over it, while it’s unclear what happens to the Dutchman. The production and staging are no help, and I found this most exciting of Wagner’s early operas lacked drive and purpose.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in