Longborough Festival Opera, refuge for British Wagnerians fleeing unidiomatic musical performances and idiotically irrelevant and insulting productions, has rounded off its Wagner canon with its first Der fliegende Holländer. Next year a new production of the Ring begins, so presumably the small stage is considered inappropriate for the three Wagner dramas with indispensably large choruses. Not that Holländer can do without a chorus in Act Three, and very impressive it is in this production by Thomas Guthrie, but we only saw the townsfolk, and I think the Dutchman’s crew was pre-recorded, though perfectly synchronised. The conducting was, as always, in the sure and inspired hands of Anthony Negus, and the orchestra, after some blips in the Overture, was superb.

Even so, Act One took time to settle down. The dopey Steersman was delightfully sung by William Wallace, and Simon Thorpe as the Dutchman produced a decent account of his monologue, Wagner’s first wholly characteristic utterance. But the odd scene fell flat, those that were comically intended but not usually comically effective, such as the Dutchman’s legato lines as he senses the hope of redemption, while Daland, here in gravelly voice, gloats over the prospective wealth he is being offered. Everything perked up when we moved to Act Two — no scenery, by the way, just threatening clouds — and Senta’s ballad, sung with superb incisiveness and intensity by Kirstin Sharpin. The climactic duet between her and the Dutchman — she determined to sacrifice herself for him ‘whoever he may be’, he incredulous but half-believing that he has found ‘the Angel’ he has so long sought — was marvellous, magnetic for us as for them.

As I’ve suggested, the prolonged song-fest of the townspeople and their battle with the Dutchman’s crew was exciting, and the dénouement — Wagner seems in a hurry to get it over with — urgent. Erik’s pleading aria, well sung by an indisposed Jonathan Stoughton, was integrated into the action, and the last minutes were thrilling, though it remained, as it usually does, obscure about what happens to Senta and how.

The next evening the Royal Opera staged its first new Lohengrin for 41 years, and one can only hope that the next Swan comes along sooner than that. David Alden, the director of this new one, has made sure that we are, and remain, dispirited throughout what Wagner foolishly called ‘a romantic opera’. It’s not romantic this time round: at curtain up we see several large buildings on the slant, as if things are slipping away — and certainly most of the usual pleasures of Lohengrin rapidly do.

We’re in a totalitarian regime of the 1940s or 1950s, no colours, except for the red cloak with which King Heinrich fidgets insecurely most of the time, drawing attention away from what is relevant. This is a grim and impoverished place, with Telramund in shabby clothes, and Ortrud before an office desk in a stern black business suit — Wagner wrote to Liszt at the time: ‘Her nature is politics. A male politician disgusts us, a female politician appals us.’ They say, sing, things that, if we follow the surtitles or know the text well, will strike you as rubbish, as indeed will all of the action. Swan? Boat? Not a sign of them, only parting walls with Lohengrin clad in a pop idol’s white suit. While it’s clearly a police state, with many people brandishing rifles, Telramund does strangely have a sword to fight Lohengrin with, while Lohengrin has nothing at all, he just waves his arms with magic intent.

Andris Nelsons seems to me a less good Wagner conductor than he was when I first heard him conduct Lohengrin in Birmingham. Mannerisms have crept in. The Prelude began almost inaudibly and swelled to a vulgar climax. Too often expression seemed plastered on from the outside, imposed rather than elicited. The wonderful melody that unfolds in the orchestra after the scene between Elsa and Ortrud in Act Two was pulled around so much as to be unrecognisable. Of course Wagner’s orchestration in this opera is so astounding that it must be a temptation to dissect it.

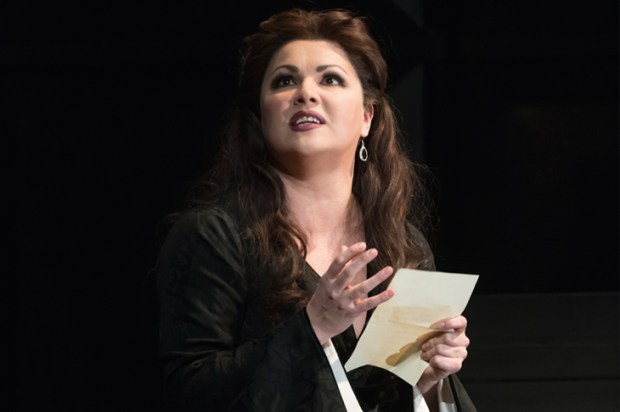

Klaus Florian Vogt is the hero, or would be if this production allowed for one. No good arguing about Vogt, he will always divide opinion. When he sings softly, as in his first few phrases, he sounds as if he should go home to Aldeburgh. When he sings out he is impressive, but the alternation between the two is disconcerting. Jennifer Davis as Elsa made a big impression, quite rightly, after she emerged from a trapdoor in the floor to begin her defence. Charming to look at, radiant to hear, she is a star. The villains were less impressive, Christine Goerke a rather tame Ortrud to hear, though not to see, and Thomas J. Mayer as Telramund too much of a wimp. For all his prescribed fidgeting, Georg Zeppenfeld impressed as King Heinrich. The chorus was tremendous, if only their contributions had been in a worthier cause.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in