‘She is a princess endowed with all the virtues of sex; long experience has taught her how to govern these people… I think that if Her Highness could govern in her own way, everything would turn out very happily.’

The ‘princess’ in question was Isabel Clara Eugenia, Infanta of Spain and regent of the Spanish Netherlands; ‘these people’ were the pesky, ungovernable Flemings and the author of the glowing testimonial was Peter Paul Rubens who, since the death of Isabel’s husband the Archduke Albert in 1621, had become her trusted diplomatic adviser. It was quite a step up for a mere court painter, especially one with a skeleton in the family closet. Before Peter Paul’s birth his lawyer father Jan had been adviser to another princess, Anna of Saxony, with whom he had had an affair that produced a son. In 1571 he had been arrested and thrown into prison, from which he was released only through the generosity and persistence of his ever-loving wife. Maria Rubens stood by her man.

Rubens’s mother was the formative influence who turned him into a champion of the female sex. That’s the idea, anyway, behind Rubens & Women, Dulwich Picture Gallery’s new exhibition – and for those who think ‘Rubens & Embonpoint’ might be a better title, the show amasses some convincing evidence.

Unlike Rembrandt and Hals, Rubens rarely painted companies of men; he does seem to have preferred the company of women. And the women he painted, real and mythological, were forces to be reckoned with: they wielded power on Olympus and on Earth. His Maria de’ Medici cycle for the Luxembourg Palace was the first such series to celebrate the achievements of a woman, and in his portraits of the French queen mother and the Archduchess Isabel – two of the 17th century’s most powerful women – he made no attempt to flatter their female vanity. He painted Isabel as a plain Jane in the habit of a Poor Clare and drew the dowager Maria de’ Medici from below looking as jowly as Margaret Rutherford, and more severe. Yet the expression in the eyes of both women hints at an empathy between artist and sitter.

Rubens wasn’t one of those neurotic portraitists who demand total silence from their subjects. One sitter described how the artist would be listening to a reading of Tacitus, dictating a letter and carrying on a conversation while busy at the easel. It was obviously not boring, and by all accounts, he was absolutely charming. And although he was said to dislike portraiture, he did the business: in her full-length portrait of 1606, the Genoese banker’s wife Marchesa Maria Serra Pallavicino looks a million denari. But in his family portraits, he took things to another level: the faces of his first wife Isabella Brant and their 12-year-old daughter Clara Serena sparkle with life. Poignantly, these paintings would become memorials after Clara died in 1623 and Isabella followed three years later.

Isabella may have modelled with her younger son Nicolaas for the intimate ‘Virgin in Adoration before the Christ Child’ (c.1616-19); Rubens’s second wife, Helena Fourment – 37 years his junior and reportedly ‘the loveliest woman in all of Flanders’ – was better suited to playing goddesses. Rumour had it that she posed for Venus in Rubens’s ‘Judgment of Paris’ in the Prado, a picture the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand deemed to have ‘only one fault, the goddesses are too naked’. This the artist could not be persuaded to correct, ‘as he maintained that it was essential for the appreciation of the painting’. Quite.

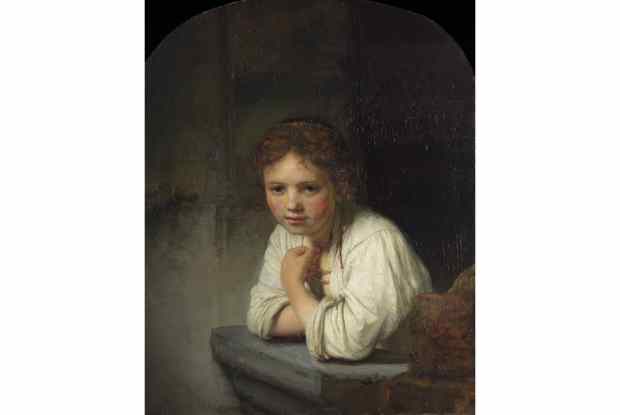

There’s endless debate among art historians about whether 17th-century Netherlandish artists drew women from life. Though they wouldn’t have advertised the fact, it must have gone on: the evidence is there in drawings in this show. Rubens could riff on antique statuary with the best of them while insisting that paintings shouldn’t ‘smell of stone’. True, his ‘Psyche’ (c.1609-12) is quite obviously a bloke with toned abs and added mammaries à la Michelangelo, but the models for other drawings are plainly women. Matisse could have painted ‘La Danse’ from imagination, but the modelling of the flesh in Rubens’s dancing ‘Three Graces (1636)’– all, incidentally, with Helena’s face – demands study from life.

Male or female, Rubens is the great painter of tactile flesh: the pudgy shoulder of his sleeping Christ Child (see above) cries out for a squeeze. In the mythological romps in the final room, he delights in contrasting roseate nymphs with sunburned satyrs. The riot of colour in these paintings would have horrified Blake, who thought Rubens’s pictures ‘the most wretched Bungles… His shadows are of a Filthy Brown somewhat the Colour of Excrement,’ he scribbled in the margin of his copy of Reynolds’s Discourses; ‘His lights are all the Colours of the Rainbow.’ In the battle between Rubenists and Poussinists Blake sided with Poussin, but in a battle between nymphs and satyrs I’d back Rubens’s nymphs. Under that Rubenesque exterior, they’re solid muscle.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in