Trivia question: name a famous Lithuanian. Google came up with four I’d never heard of and one I had: Hannibal Lecter. It seems that Lithuanians are famous only in Lithuania unless they’re the monstrous inventions of non-Lithuanians – an injustice Dulwich Picture Gallery is helping to correct with its M.K. Ciurlionis exhibition.

Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionis is not just Lithuania’s most famous artist; he is also the country’s most famous composer. On his death in 1911 he left more than 400 musical compositions and more than 300 artistic ones, the latter squeezed into six short years before pneumonia carried him off aged 35. The son of a church organist, he was a musical prodigy, mastering the piano aged five and the organ aged six. But in 1902, after completing his musical studies in Warsaw and Leipzig, he decided to become an artist.

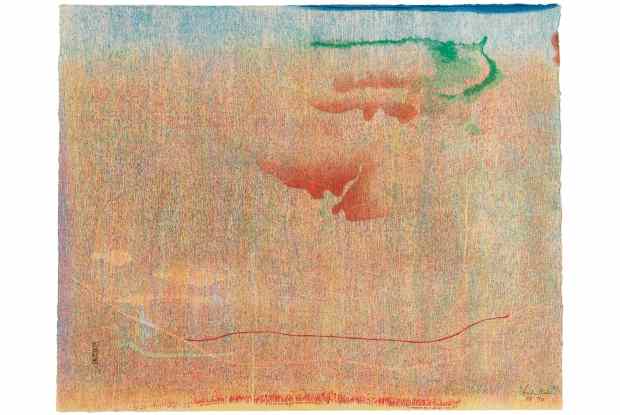

As a music student he had pursued interests in the natural sciences, astronomy, geology, philosophy and psychology, and his teacher at Warsaw’s School of Fine Arts, the Polish painter Kazimierz Stabrowski, was an adherent of the theosophical movement founded by the Russian mystic Madame Blavatsky. He became obsessed with the puzzle of man’s place in the cosmos and found painting better suited than music to exploring his ideas on the subject. Apart from the large canvas ‘Rex’ (1909) – a national icon – he worked in tempera on paper or cardboard. The materials were cheap – he made no money from his art – and the modest scale was suited to compositions that are less like paintings than illustrations of a fantasy world of his own invention: a mystical fairy tale of a free Lithuania, then in the grip of a national struggle for political and cultural independence. He was a dreamer. ‘I don’t know how time slips by,’ he wrote to his fiancée Sofija Kymantaite in 1908; ‘everything vanishes and the next moment I’m wandering on the distant horizons of my dream world.’

Lithuania was the last country in Europe to adopt Christianity and there’s a healthy dose of pantheism in Ciurlionis’s iconography, spiced with a dash of Old Testament prophets, a pinch of the Hindu Vedas and a shot of Egyptian astrology. He painted a Zodiac cycle and dated his letters with star signs. With their visual repertoire of mountains, castles, bell towers, bridges, crowned kings and queens, angels, swooping birds, suns, moons, stars and fantasy clouds assuming organic shapes, his compositions would make fantastic album covers. A New Ager before his time, he would reach a bigger audience in Glastonbury than Dulwich.

Used to thinking in musical terms, Ciurlionis imagined ‘the whole world as a great symphony’ and divided his seven ‘Sonata’ cycles into andante, allegro, scherzo and finale movements. His three-part ‘Sonata of the Sea’ (1908) was painted while staying in the spa resort of Palanga, where he frightened Sofija by swimming out of sight and returning with tales of life beneath the waves. The ‘Andante’ movement features a city under the sea. Like deep-sea diving, Ciurlionis’s art can be disorientating; you don’t always know which way is up. It was as a teenage student at an orchestral school on the coast that he developed his love of the sea, along with the first of the depressions – ‘dark clouds that gathered in my imagination’ – from which he suffered throughout his life.

There are shades of Hokusai’s ‘Great Wave’ in the foaming breaker about to fall on the fragile boats in the ‘Finale’ to ‘Sonata of the Sea’ (see below), and there are nods to Bruegel’s ‘Tower of Babel’ in ‘The Altar’ (1909) and ‘Fantasy (The Demon)’ (1909). Stravinsky, an early collector, compared Ciurlionis to Odilon Redon – symbolism was in his bones. But he was a forerunner as well as a follower. His brooding dreamscapes presage the surrealism of Max Ernst and his towering cities foreshadow Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. His ‘Sonata of the Stars’, meanwhile, puts him in contention for the increasingly contested title of inventor of abstraction. Kandinsky would have seen Ciurlionis’s commemorative exhibition in Moscow in 1911, the year he painted his abstract ‘Composition V’. Both he and Hilma af Klint, another challenger for the title, were converts to theosophy. Scratch the surface of early abstraction and you find Madame Blavatsky, so perhaps the honour should belong to her.

The ‘Vignette’ ink drawings in the final room are the most purely abstract images in this show, but the works I liked best were rooted in reality. I wondered why the steamy atmosphere of ‘Sparks’ I, II and III (all 1906) made me think of Monet’s ‘Gare Saint-Lazare’ with added fairy lights until I read that the series was inspired by a boat trip on the Nemunas River when the stars ‘enveloped in spheres of miraculous fog… were scattered by a black monster charging by. The air was shattered by the sounds of the symphony of the night storm… It turned out to be a train moving across with great commotion.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in