There’s a photograph in Nicole Eisenman’s Whitechapel exhibition of the 28-year-old artist, in 1993, sitting at her easel with a big bow in her hair and a bevy of studio assistants – a feminist piss-take of the trope of the heroic male artist surrounded by adoring acolytes. Her resemblance in the photo to stand-up comic Sarah Silverman is not entirely coincidental; Eisenman is Jewish-American and funny. At the time she was producing the bawdy satires on downtown New York lesbian life – battles of the sexes redrawing Michelangelo’s ‘Battle of Cascina’ in the style of Where’s Wally? – which plaster the wall facing the exhibition entrance. She could have been a cartoonist, but she chose art.

Eisenman could have been a cartoonist, but she chose art

Her raucous lesbianism put her on the map, but by the Noughties she wanted a bigger canvas and moved on from sexual politics to broader issues. ‘The Triumph of Poverty’ (2009) addresses the sub-prime meltdown in a composition quoting from Holbein and Bruegel in the carnivalesque language of James Ensor; later allegories are directed at the Tea Party and the MAGA disciples of Donald Trump.

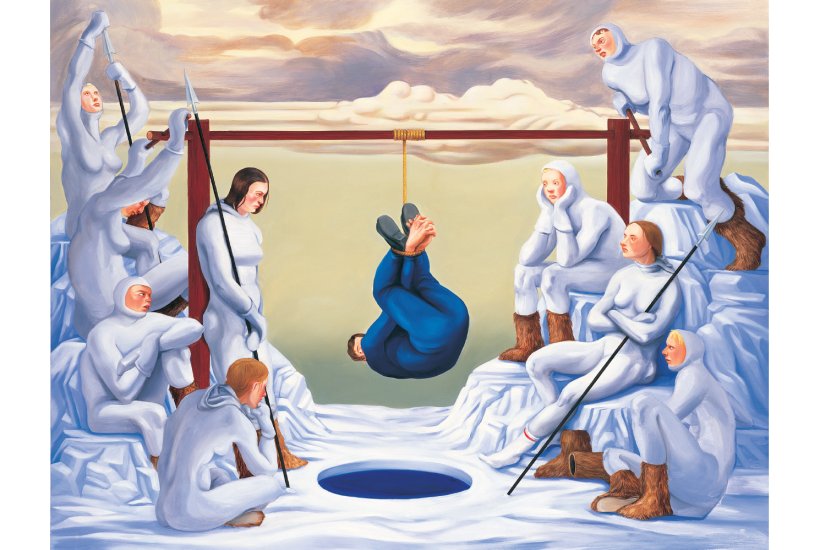

Like the great cartoonists, Eisenman is an art-historical magpie, as happy filching from Ingres’s ‘Angelica Saved by Ruggiero’ as from Renoir’s ‘Bal du moulin de la Galette’. She owes the pop-eyed cyclops in her series on contemporary culture’s screen addiction to Philip Guston, but has not inherited his feeling for juicy oil paint. Her paint surfaces are strangely impersonal, as if eschewing the machismo of the gestural. Give her ink on paper, though, and she’s a different artist: her monoprints of heads from 2011-12 are wonderfully witty and expressive. Her sculptures can be laugh-out-loud funny, too. Her saving grace is her humour, which she looks in danger of losing in her recent monumental painting acquired by New York’s Met, shown in the final room in reproduction. ‘The Abolitionists in the Park’ (2020-21) includes portraits of Eisenman and friends at an ‘Occupy City Hall’ protest after the murder of George Floyd. Hailed as a ‘history painting’, it’s actually a portrait of the artist painting herself into the right side of history. It’s as if Picasso had recorded himself demonstrating against the bombing of Guernica.

Let’s hope she’s not beginning to take herself seriously; that would be R.B. Kitaj’s undoing. When the 27-year-old American artist arrived at London’s Royal College of Art in 1959, his friend David Hockney logged him as ‘a much more serious student than anyone else’. A bibliomaniac, he was also the most art-educated. Like Eisenman’s, the paintings in his exhibition at Piano Nobile are packed with art-historical references, from the Giotto monk cast as ‘Marrano (The Secret Jew)’ (1976) to the sciapod in ‘Welcome Every Dread Delight’ (1962) copied from a medieval relief in Sens Cathedral. His literary allusions are equally eclectic: ‘Welcome Every Dread Delight’ comes from a poem by the 18th century poet Edward Young, ‘General of Hot Desire’ from one of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

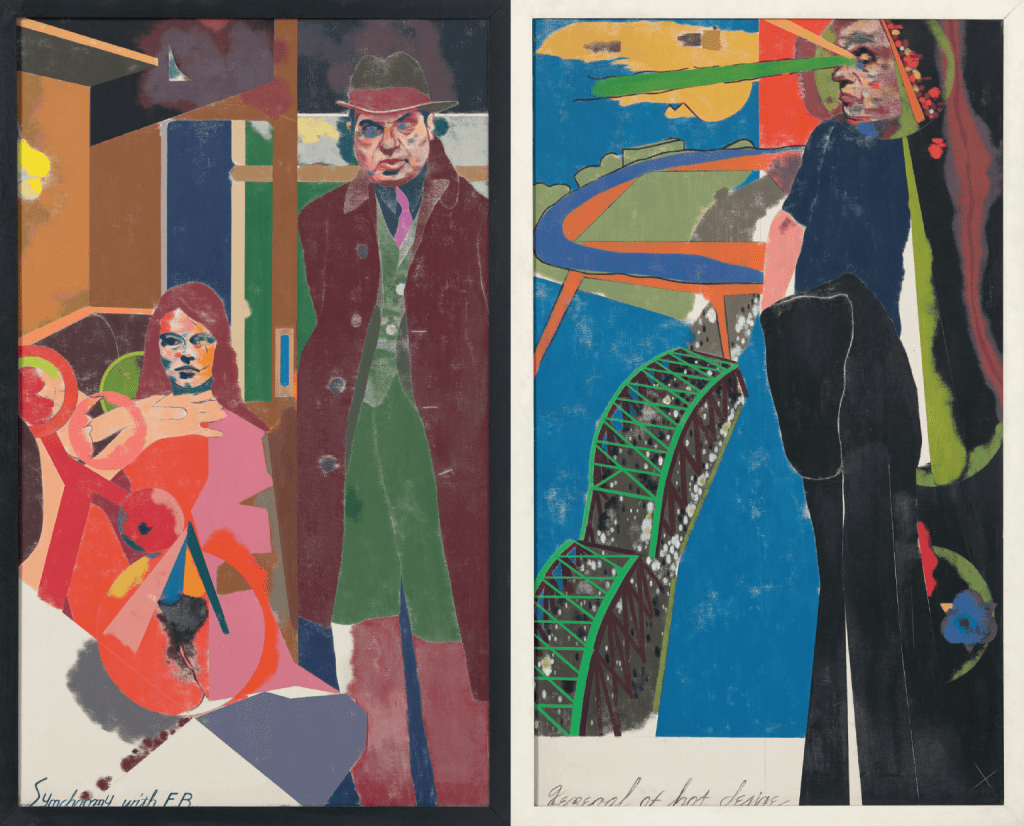

‘Synchromy with F.B. – General of Hot Desire’, 1968-69, by R.B. Kitaj. Credit: R.B. Kitaj Estate, courtesy of Piano Nobile, London

‘Synchromy with F.B. – General of Hot Desire’, 1968-69, by R.B. Kitaj. Credit: R.B. Kitaj Estate, courtesy of Piano Nobile, London

‘What Happened’ would make a good subtitle for this show too. Who knows what’s going on in the pop arty diptych ‘Synchromy with F.B. – General of Hot Desire’ (1968-69) featuring Francis Bacon turned out like a dandified mafia don (see above). Is that Christine Keeler being throttled on the chair beside him? The meanings of what Kitaj called his ‘surreal-dada-symbolist strain’ of paintings are harder to unpack than their references, yet an image like ‘Junta’ (1962) has a clear political context. ‘I watch political events like I watch baseball and boxing,’ he said. ‘Very closely.’

When Kitaj’s wife died, he blamed her death on the savagery of the critics’ attacks

Kitaj is a ‘polemical’ artist, noted John Russell in a review of his first exhibition with the Marlborough in 1963. ‘He has brought the subject back into painting and, what is more, he has brought history-painting back to life.’ Unlike Eisenman, he did it without obvious messaging and it worked fine until he infuriated critics at his 1994 Tate retrospective by providing explanatory captions to his paintings. When his beloved wife Sandra Fisher died of a brain haemorrhage months later, he blamed her death on the savagery of the critics’ attacks and abandoned his adoptive city for Los Angeles, where he poured out his grief in a series of mystical paintings of himself and Sandra as angels, pun intended.

‘I don’t fit in here,’ he later said of London. ‘Maybe it’s the Jewishness.’ More likely it was the intellectualism and the un-English tendency to show it off. Thirty years on, this mini-retrospective is a reminder of how exceptional an artist he was. Robert Hughes’s observation in 1980 that ‘Kitaj draws better than almost anyone else alive’ is even truer now than it was then. No contemporary artist can breathe life into charcoal like Kitaj does in the portraits of his adolescent daughter Dominie in this show.

‘When you get it right,’ he once said about drawing, ‘you get the whole world in, like Degas, Dürer and Hokusai did. Then you can do anything.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in