In March 1913 two horse painters met at the Lyceum Club to discuss the establishment of a Society of Animal Painters to raise the profile of their genre. Of the two, it was Alfred Munnings whose profile needed raising. Lucy Kemp-Welch had been a celebrity since her twenties when her 5x10ft canvas ‘Colt Hunting in the New Forest’ caused a sensation at the 1897 RA Summer Exhibition and was purchased by the Chantrey Bequest for the new National Gallery of British Art on Millbank.

The daughter of a Bournemouth solicitor, Kemp-Welch had been riding and sketching horses since the age of five and had developed a photographic memory for catching them in action. Her first Academy submission, ‘Gypsy Horse Drovers’ (1894), painted while still a student at Hubert von Herkomer’s Art School in Bushey, was inspired by the sight of gypsies driving horses through the village to Barnet Fair; rushing out after them, she had dashed off an oil sketch on the wooden slide of her paintbox. As fresh as the day it was painted, the sketch hangs in the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery’s current retrospective curated by David Boyd Haycock, author of a new biography of this extraordinary woman who threw herself into every activity she depicted, whether rounding up colts or hauling timber.

To Kemp-Welch, every horse was an individual: ‘Mixed Company at a Race Meeting’ (1905) is a tour de force of equine group portraiture, the foreground horses’ heads so close to the picture plane you could pat them and feed them sugar lumps. A race meeting was an unusual subject for a painter who preferred working horses, finding racehorses ‘too perfect, polished and shiny… Perfection in the subject painted does not lead to interest in the picture,’ she thought. She made an exception for the Royal Hanoverians in ‘Aristocrats’ (1928), stars of Sanger’s Circus which she followed on the road every summer until too old to crank her old banger ‘Spitfire’.

Despite showing in every RA Summer Exhibition between 1895 and 1930 bar one, Kemp-Welch was never elected an academician. She was considered for associate membership after ‘Colt Hunting’, but worries about who would escort this quiet little woman into the annual Academy banquet scotched her chances. The RA was a boys’ club. Munnings, a party animal, was a better fit; within six years of their Lyceum meeting, he was an associate member.

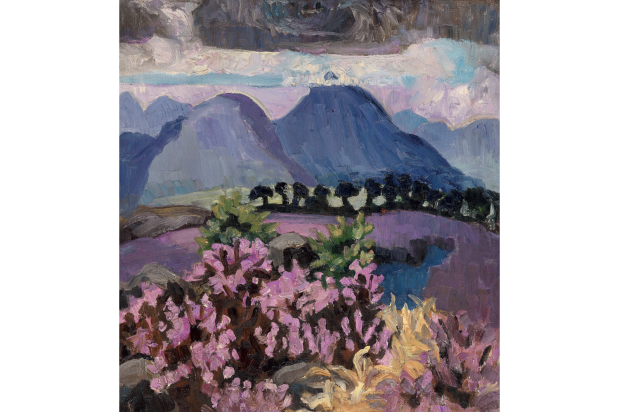

Like Kemp-Welch, Munnings was a precocious draughtsman, practising as a child on the horses that came and went from his father’s Suffolk mill. At the age of 20, the jockeys and gypsies at Bungay Races awakened the love of colour that is the focus of the Munnings Art Museum’s current show. The loss of sight in one eye while helping a puppy out of a thorny hedge only increased his awareness of colour: he became a connoisseur of florid complexions set off by the scarlet flash of a hunt coat.

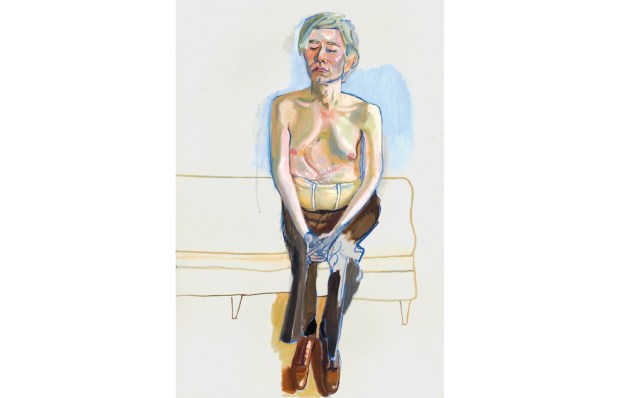

‘Pink is an artist’s colour,’ said Munnings, and curator Marcia Whiting has assembled a Barbie wall of pinkish paintings to prove it. But he was no Ken. Moody and boozy, he achieved the rare distinction of being suspended from the Chelsea Arts Club for foul language. His first wife Florence tried to kill herself on their honeymoon and succeeded two years later; his second, Violet, took him in hand and appointed herself his business manager. He complained bitterly when she dragged him away from painting gypsies in Hampshire to fulfil a commission to paint the thoroughbred stallion ‘Rich Gift’ (1921), but he did him proud, catching the iridescence in his glossy brown coat. Unlike Kemp-Welch, he relished ‘the sheen of a clipped horse’, although he champed at exchanging country subjects for equestrian portraits. ‘It meant painting for money,’ Violet freely admitted. ‘He was never such a good artist after he married me.’

The first world war made Munnings. Kemp-Welch had desperately wanted to go to France but resigned herself to painting gun teams training on Salisbury Plain; Munnings’s service as an official war artist with the Canadian Cavalry Brigade established his reputation. Elected ARA in 1919 and RA in 1928, he rose to become president in 1944. But with the demise of the working horse and the advent of modernism, both painters found their subjects and styles outdated. If Kemp-Welch is best remembered today for her illustrations to Black Beauty, Munnings went down in British art history for his notorious speech at the 1949 Academy banquet in which he slagged off the entire British art establishment for being in thrall to ‘foolish daubers’ like Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso. He resigned as president but went down fighting. The Barbie wall includes ‘Does the Subject Matter?’ (1953-56), the lampoon he showed at the 1956 RA Summer Exhibition three years before his death picturing Tate director John Rothenstein with a group of men in grey suits admiring a modernist sculpture in front of a wall of Picassos – in the company of a Selfridges model in pink.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in