London’s City Hall stands empty. The bulbous, Foster + Partners-designed ‘glass testicle’ — in Ken Livingstone’s words — occupies one of the best sites in the capital: Thames-side, squaring off to the Tower of London, and overlooking Tower Bridge. But in December, its occupiers — the Mayor, the London Assembly and the Greater London Authority — deserted their glitzy £43 million headquarters for a cheaper building more than five miles east at the Royal Docks in Newham. It took them less than 20 years to outgrow their purpose-built home.

According to the architectural commentator John Grindrod, City Hall is a giant glass-and-steel metaphor. ‘The building represents the role of the London mayor in some sort of horrible way,’ he says. ‘Prime site, looks fantastic, brilliant symbol — but it’s not big enough for the job.’

Yet despite City Hall’s demotion, Grindrod argues that the building — which opened in 2002 — is one of a clutch of confident, neo-futuristic, turn-of-the-millennium UK projects that embodied a collective optimism unique to that time. And we should think again about their value.

In his new book Iconicon: A Journey Around the Landmark Buildings of Contemporary Britain, Grindrod explores how these buildings captured national aspirations at a moment before the trauma of 9/11 and the financial crash. Many were the work of the so-called ‘starchitects’ of the era: Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Zaha Hadid and so on. Some are civic; some are commercial; many have endured, and some have failed.

They include the Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff (‘could not be more successful,’ says Grindrod); 30 St Mary Axe — AKA the Gherkin — (‘it is hard to think of a building from that era that is more loved’) — and of course the Dome, the vast exhibition centre that was to be the heart of the nation’s millennium celebrations, and the single structure most associated with the New Labour era. In 1998, Peter Mandelson sent out a press release: ‘I want the Dome to capture the spirit of modern Britain — a nation that is confident, excited, impatient for the future.’

Heritage organisations share Grindrod’s thinking. ‘We see it as a very significant era,’ says Oli Marshall, head of campaigns at the Twentieth Century Society. ‘Probably comparable to the post-war period, a time of great self-confidence and national renewal, which informs our putting forward for listing.’ The society may even consider changing its name, he says.

A few of the best-known examples will be eligible for listing by Historic England in the next few years (an application can usually be considered by the public-heritage body 30 years after ground was first broken, though some are listed earlier). One — Future Systems’ microphone-shaped J.P. Morgan Media Centre at Lord’s Cricket Ground, winner of the Stirling Prize in 1999 — has already been the subject of a preservation campaign, after plans to alter its interiors caused alarm (they have since been withdrawn).

What led to all this manic, ambitious building? So much cash was sloshing around from the National Lottery (which started in 1994) that the Millennium Commission was set up by the Major government to try to find projects to give it to. In Grindrod’s book, Michael Heseltine, one of the commissioners, recalls having to spend £2 billion in six years. Many of the buildings they funded are so distinctive that it is almost impossible to remember life without them: the Eden Project, Tate Modern, and of course the Dome. Meanwhile the City of London was expanding fast — and with it came the cranes.

When the time comes, says Grindrod, the Dome — now the vast and successful O2 concert venue, temporarily laid low by Storm Eunice, which ripped through the fibre-glass canopy last week — should be near the top of Historic England’s priority list. ‘It’s only really with a bit of time and distance that you can look back and think about it, without the paraphernalia of our assumptions and media snarkiness,’ he says. ‘It’s a lot more interesting than we allowed it to be at the time.’

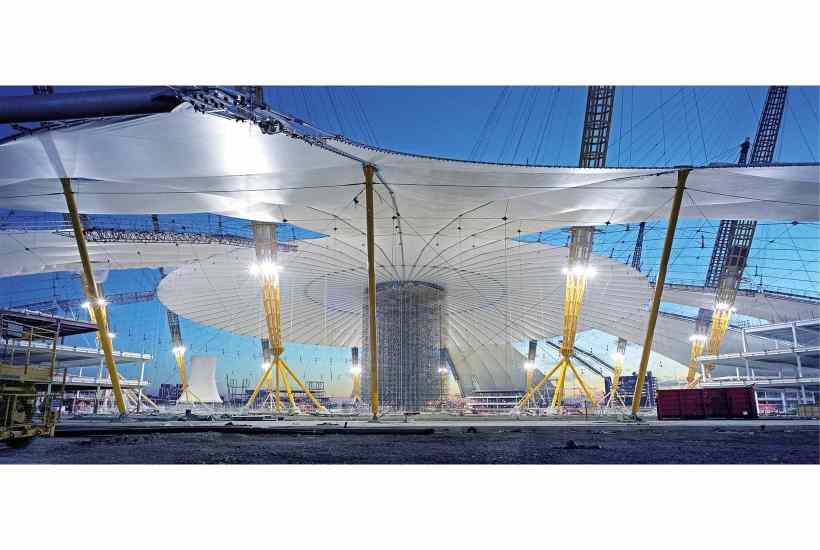

Like the Lord’s microphone, the Dome is a literal representation — an example of so-called programmatic architecture, or nearly. It crouches on the Greenwich peninsula, out of proportion to its surroundings with its yellow support towers and strung cables mimicking a circus tent.

When it was built in 1999, on ground contaminated with toxic sludge from the nearby gas works and at a cost of more than £750 million, it was roundly jeered. The late Richard Rogers, one of its architects, once commented that the Dome ‘couldn’t have had a worse reception if you’d worked hard to deliberately upset everybody. The press were violently against it.’

Today, the Dome’s original interiors are long gone, ripped out to make way for food courts and the like. That is not necessarily a problem, according to Deborah Mays, head of listing at Historic England, the public body that recommends listings approvals to the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. ‘We’re open-minded,’ says Mays. ‘The criteria include historical interest, which includes social history. Arguably marking the millennium is that. And changes do happen. Many buildings have been listed where it’s understood there will be flexibility to the interiors.’ Mays says the Dome will be ‘carefully considered’ for listing.

There were failures and hubris, of course, what Grindrod describes as ‘abstract ambitions’ to transform city centres outside London without sufficient thought into whether such projects were necessary. ‘“Vibrant” was the most overused word of the era,’ he says.

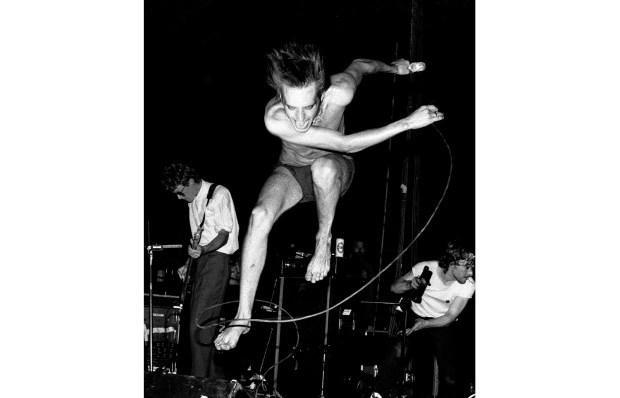

He points to the National Centre for Popular Music by Branson Coates in Sheffield, a £15 million Millennium Commission project built to look like enormous steel drums, and funded mostly by the National Lottery. It opened in 1999 and closed just over a year later (it is now the student union of Sheffield Hallam University).

‘It is an adorable stunner of a building,’ he says. ‘A really over-optimistic project. But they were in a desperate rush to get everything ready for the millennium.’ Another Millennium Commission flop was Urbis, a short-lived museum of urban design in Manchester, a glass-and-steel fin towering over Cathedral Gardens. It is now the National Museum of Football. ‘That makes much more sense for Manchester,’ says Grindrod.

Others, like 30 St Mary Axe in the City of London, have been disregarded. ‘It’s hard to think of a building that’s been so badly treated as the Gherkin,’ he says. ‘It was so successful they blocked it off with a lot of copies. But now it’s the only thing anyone wants to see in that cluster.’

One 30-year-old lawyer, who works on one of the highest floors of the Gherkin, laments its obliteration. She was too young to recall the time when her office was London’s star skyscraper, before a cluster of taller buildings blotted it from the skyline.

‘I was only a child. I didn’t know there was a time when it could be seen across London. It’s such a shame that they have blocked off the view.’ She loves to watch dramatic weather systems advance across the city, from its floor-to-ceiling windows. ‘That’s one of the best things.’ Another office pastime is watching people out on the street trying to capture the Gherkin’s best angle for a selfie.

What of City Hall? Richard Brown, now an urban planning consultant, was part of the team that set up the GLA, and one of the first people to work in it. ‘I can’t immediately see any future for that building,’ he says. ‘It’s not easily adaptable or usable for anything else. As much as it is flawed, the move seems like a retreat. It’s all very well in London to say the future is east, but it’s not there yet.’

Brown says the original vision for City Hall — a near-utopian idea for Londoners to wander from the South Bank into the debating chamber to watch democracy at work — never materialised. The building opened nine months after 9/11 and from the outset needed airport-style security gates. ‘There was that whole idea of openness, and suddenly the reality was: “Empty your pockets into this tray”.’

Grindrod fears City Hall is vulnerable to development or even demolition: ‘If we don’t list things people ruin them,’ he says. ‘Could everyone stop making their mark on things all the time and just try to respect things as they are?’

Brown, too, fears it may be lost. He recalls being excited to work there: ‘It was so self-consciously modern.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Iconicon: A Journey Around the Landmark Buildings of Contemporary Britain by John Grindrod is published by Faber.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in