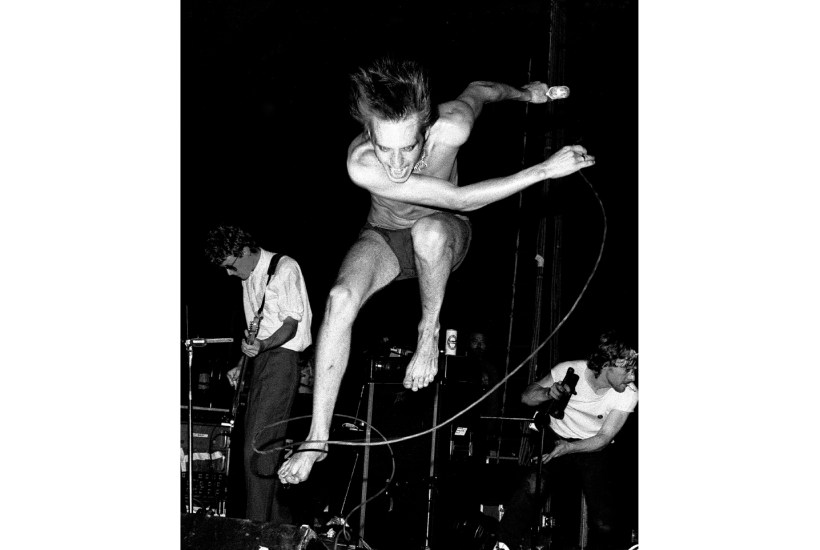

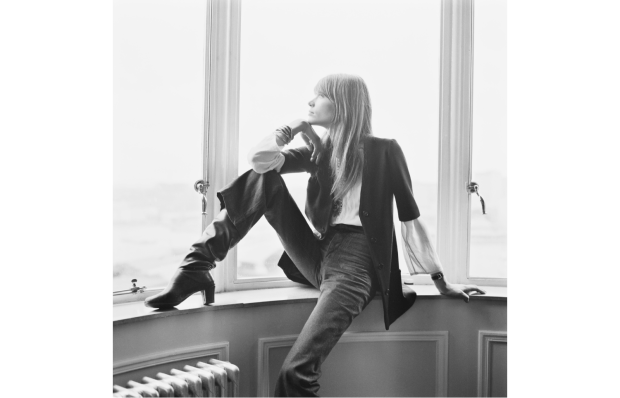

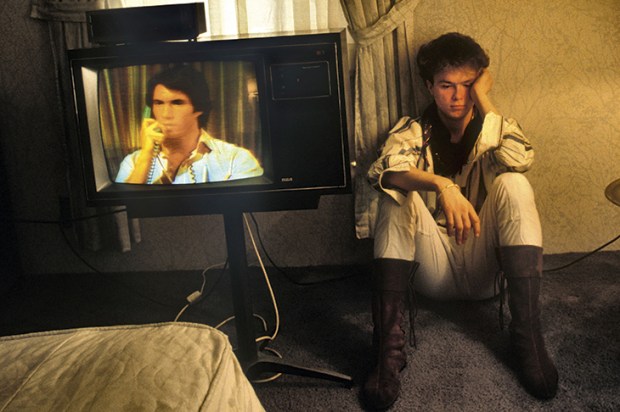

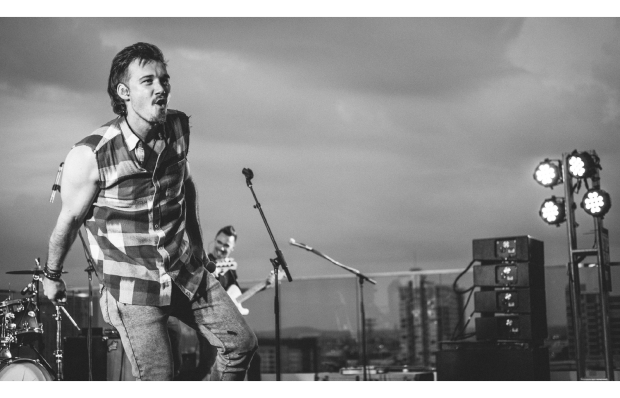

More than 40 years on, every town still has them, wandering the streets with pale skin, more make-up than you can find in Superdrug, swathed in acres of black fabric. Goths, rather unexpectedly, have turned out to be the great survivors among pop subcultures. Others have risen and faded, but the goths – laughed at, ignored, dismissed – have endured, seeing their style and their musical tastes slowly incorporated by everyone else (there’s even a goth version of hip-hop, known as ‘horrorcore’).

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in