The star system is a false hierarchy: the best rarely make it to the top. I thought of this recently when it was announced that David Warner had died. Few outside acting could name him, though you may have seen his head flying off in The Omen, a film in which heads are cheap. Warner was a Manchester-born jobbing actor: a character actor, better defined by what he is not, which was a star.

I could write pages about why a star is a star, and a character actor remains a character actor, but the most significant reason is simple. Warner was brilliant but he was not handsome. Yet he did, in Time Bandits, a tale of little people thieving through history with a magic map, steal a film not only from Sean Connery – playing King Agamemnon with an Edinburgh accent, which surprisingly does work – and Ian Holm, a notorious film-stealer himself, but also from Ralph Richardson, as a peculiarly British God: God the weary bureaucrat.

Warner played Evil as a pantomime dame with curling nails, locked in a mirrored fortress with his ambition and his fury. I’m faintly surprised he isn’t standing for leader of the Conservative party because he’d win. He met the part with ecstasy: at one point he transformed himself into a carousel. Nothing I saw in the cinema in my childhood matched him and when he died, I mourned the films he could have made.

Hollywood has always been a star factory, and, a century in, little has changed on the production line. It likes a kind of glowing perfection in women, as if they are designed to be lit, not touched: Natalie Portman and Scarlett Johansson are living statues. Lana Turner and Ava Gardner, luminous but not actors – though Gardner broke free at last in Night of the Iguana – were sent to star school, to learn not to stare down the lens. This was parodied in A Star is Born: Esther Blodgett (Judy Garland) was turned into a painted hag by the star factory and the film bombed for being unbelievable. Better actors – Agnes Moorehead, who had the best moment in Citizen Kane with one word (‘Charles!’) and Joan Greenwood of Kind Hearts and Coronets – were denied stardom. They were too interesting. There are exceptions of course, and they flare through luck or a brief change in fashion. Film noir, for instance, was kind to real actors, and Marilyn Monroe is, whatever she looked like, the greatest comedienne in cinema. Bette Davis’s flashing eyes and Judy Garland’s voice could never be gainsaid and attempts to monetise the 1960s counterculture allowed a weirder leading man to flourish: Jack Nicholson.

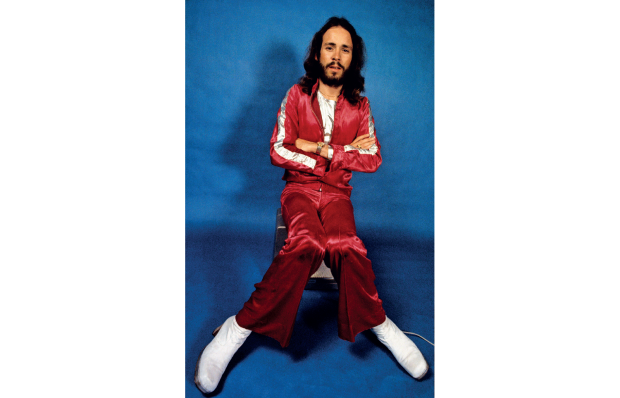

But Hollywood always regresses to its hunger for simple flesh. Leading men must have a meaty quality. Clark Gable begat Burt Lancaster begat George Clooney begat Chris Pratt. They are not great actors and watching them try to be is painful: they can’t be. Do they know it? A great actor needs ambivalence. Cary Grant had it and hid it – hence his fame. Paul Scofield couldn’t repress it; Tom Hollander and Roger Allam still have it. They quake with it: with words denied. A great star has the opposite of ambivalence: a horrid certainty. He is essentially a talking brick, anchoring the film to this world. Gene Kelly was a singing brick. Brad Pitt is a topless brick. Tom Cruise is a brick that does its own stunts. Paul Newman in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is called Brick.

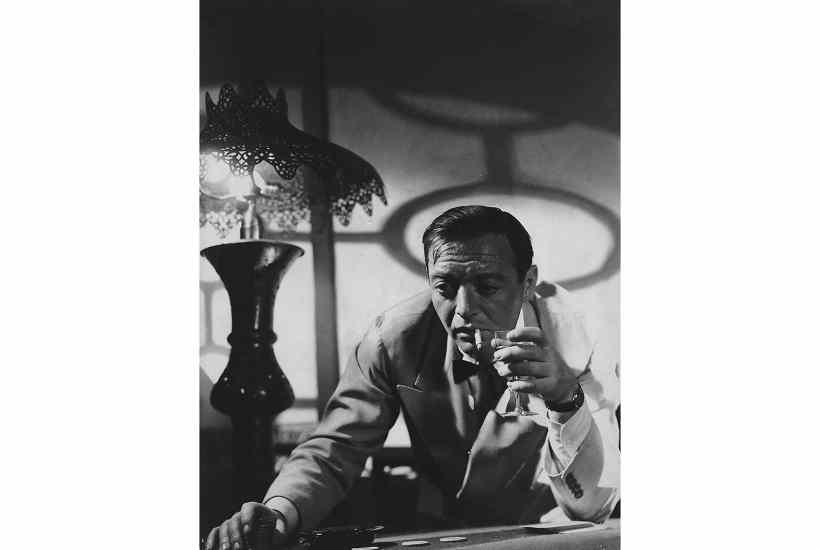

If it’s a performance you seek, look at the edges, where it is allowed and – if you care about cinema at all – necessary, because it is all you will get. Casablanca is the best example. It’s a masterpiece but not because of its leads: two-parts absence to one-part Humphrey Bogart (a suave brick). Paul Henreid, as Victor Laszlo, was the world’s most boring freedom-fighter, and I have always wondered how Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman), who wore only white, managed to launder her clothes in Casablanca. Isn’t she supposed to be a refugee? But that’s all I wondered. What else was there to ask a woman whose job is to be laundered while confused?

The film, rather, belongs to the supporting cast, who toss it between themselves joyfully: Peter Lorre, the criminal; Conrad Veidt, the Nazi; Leonid Kinskey, the Russian; Madeleine Lebeau, the slut, having the smallest drunken tantrum to merit a taxi home in the whole of cinema; S.Z. Sakall, the waiter; Claude Rains and Sydney Greenstreet, the lotus eaters.

Still, there are games to be had if you accept the premise: supporting actors tend to out-perform leads. Wilfrid Hyde-White was better than Rex Harrison or Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady. Marni Nixon – singing the voice of Eliza Doolittle, and Mrs Anna in The King and I – was better than all of them. Bernard Hill, whom I once saw sitting grumpily on the London Underground, was the best thing in the Lord of the Rings trilogy as King Théoden of Rohan, leaking pathos the way I imagine Treebeard leaked sap.

Ian McShane stole the remnants of the John Wickfranchise from Keanu Reeves, even if they clearly cast McShane because they couldn’t afford Al Pacino. I’m not entirely sure McShane is a great actor, but he’s a lot better than Reeves.

Sometimes there is justice, but not often enough, when the character actor is merely resting on his way to star status. I am mesmerised by Philip Seymour Hoffman as a tornado expert in Twister, a film so empty that a vacuum is literally its antagonist. Later he stole The Talented Mr Ripley from Jude Law (a pretty brick), became the best leading man of his generation, and died.

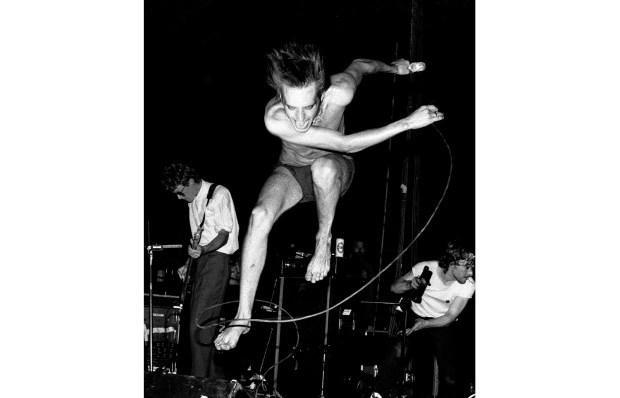

Sometimes the ambivalent do reach the top of the marquee: see Adam Driver using The Force to have Dark Side Sex with Daisy Ridley – another collection of surfaces – in Star Wars 9. Alan Rickman did it too in Die Hard and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, where he kicked the action heroes Bruce Willis and Kevin Costner where it hurts: in the performance. John Malkovich is the same. He’s too interesting – and much too ugly – to be a leading man, but when he is on screen you can’t see anything else. Then there is Benedict Cumberbatch. It happens perhaps once in a generation. It should happen more often.

As evidence I mention another performance that obsesses me. It is in Prime Suspect 4, and for me it is the best scene in television. It is Jane Tennison (Helen Mirren) interviewing a serial killer’s mother called Doris Marlow. The woman had dementia, and remembers, for Tennison, the night trauma turned her son into a murderer. I’ve never seen a better performance and it was over in moments. The actor was Joyce Olivia Redman, she was 80 when she played Doris Marlow, and she died in 2012.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in