It is 40 years ago today since Granada’s masterly adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited first beamed into British homes. This 11-part serialisation of a book originally entitled A Household of the Faith soon gathered millions of faithful householders. The autumn of 1981 was an especially cold and wet one and it was still too soon in the Thatcher premiership for her patron saint, Francis of Assisi, to have worked his magic. So while ITV was not able to deliver harmony, truth, faith or hope, it certainly provided 659 minutes of romantic escapism.

It began very soberly with the credits — a simple black screen announcing the first episode’s actors in stark white script — propelled only by Geoffrey Burgon’s majestic score. The opening scene — an army encampment somewhere in the north of England in spring 1943 — was even grimmer as the languorous voice of Captain Charles Ryder intoned: ‘Here, at the age of 39, I began to grow old.’ Their new camp happened to be beside Brideshead Castle, ‘a name that was so familiar to me, a conjuror’s name of such ancient power, that, at its mere sound, the phantoms of those haunted late years began to take flight’.

The voice of Ryder (Jeremy Irons) would, with Burgon’s oboe and horn, become emblematic of this production and both soon carried the audience back 21 years to intoxicating Oxford and his encounter with his first Flyte fancy, Lord Sebastian, second son of the Marquess of Marchmain.

But this classic had endured a very difficult gestation. Many times it seemed as doomed as the Flytes.

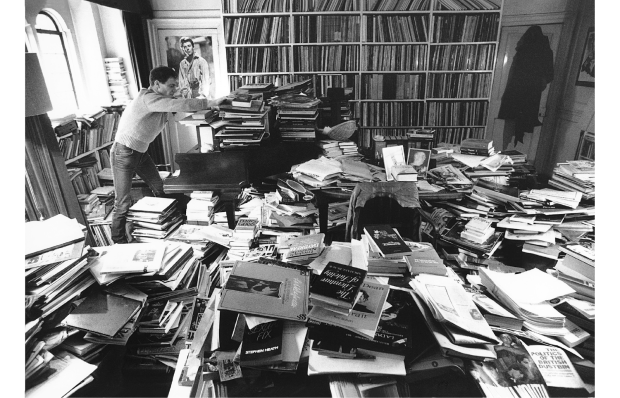

Late in the summer of 1978, Derek Granger (still with us, at 100), just commissioned by Granada to produce Brideshead, met Michael Lindsay-Hogg to ask if he would direct. As Lindsay-Hogg, who had first read the novel at 17, wrote in Vanity Fair: ‘I felt, as if from the balmy summer sky, flowers — colourful, sweet smelling — were floating toward my head.’ Eight months of costuming and casting followed, and, most significantly but covertly, the junking of John Mortimer’s script. For the rest of his life, Mortimer would beam with his crooked smile when complimented on his superb script but none of it was used. Given his eminence and the fact that he had satisfied his contractual obligations by presenting a script, he retained the credit (he was even nominated for an Emmy). But in truth the inspired, indefatigable Granger began again, with his associate producer, Martin Thompson, rewriting the script, adopting great swathes of Waugh’s prose. As Granger put it: ‘We hugged the book. We were true to its faults as well as its virtues.’

Four months into filming — after Malta, Oxford, the north of England, and the model for Brideshead, the Flyte family seat, Vanbrugh’s great domed palace, Castle Howard (so commanding it became another character) — filming was halted by a technicians’ strike.

Irons left to make The French Lieutenant’s Woman; Charles Dance — cast as Charles Ryder’s cousin Jasper — had to pull out and Lindsay-Hogg also had to leave. His replacement was 27-year-old Charles Sturridge, whose directorial experience had been a few episodes of Crown Court. ‘My God, it’s a schoolboy!’ gasped Nickolas Grace (Anthony Blanche) when he saw Sturridge. ‘Don’t worry,’ Irons told Phoebe Nicholls (Cordelia Flyte). ‘If he’s not what he’s cracked up to be, we’ll just get rid of him.’ Well, he proved an inspired choice and, dear reader, in 1985, Sturridge married Cordelia.

One bonus of the delay was the availability of Laurence Olivier as the wayward patriarch, Lord Marchmain, joining the cast with John Gielgud (Edward Ryder, Charles’s father). Although they neither shared a set nor any scenes, it was apparently their first appearance on the same bill since 1935. It was said both performances were among their best — Olivier’s astonishing death scene and miraculous conversion; and Gielgud’s howlingly funny meeting with his son: ‘Your cousin Melchior was imprudent with his investments and got into a very queer street — [he] worked his passage to Australia before the mast.’

At another stage, Derek Granger approached Granada executive David Plowright, suggesting that six hours would not do Waugh justice. To do so it would need to be expanded to 13 episodes. Plowright responded: ‘You have proposed props for a sum only fractionally higher than that paid by George III for Buckingham Palace.’ Granger countered: ‘My dear David, there is about this piece something of a trembling phosphorescence.’ Plowright conceded. How could he not?

The scheduled eight months dragged into two years. In those two years of filming, half a million feet of footage were shot; 26,000 were used. But at last, on 12 October 1981, it was ready. As Sturridge said: ‘The combination of Granada’s stubbornness, Derek’s confidence, a brilliant cast and my own unlikely mix of innocence and experience allowed something rarer. We got to make exactly what we thought.’

The British public were immediately enchanted. As one observer noted, like Charles Ryder, they were drowning in honey. The critics were generally ecstatic. ‘Sumptuous’, ‘glorious’, ‘splendid’, ‘luminous’, ‘lavish’ were adjectives used to describe the show.

Anthony Burgess proclaimed: ‘I think it is the best piece of fictional TV ever made. It is the book. In some ways, it is better than the book.’ For the Sunday Times it was ‘compulsive viewing’; for the Financial Times ‘the nearest thing to perfect in the entire history of television series’. The Times’s Michael Ratcliffe called it ‘a triumph of beauty, fidelity and relevant embellishment — in short, a hit’. He saw the narration as strengthened at every point by Burgon’s score, flowering and modulating ‘between ecstasy, alarm and grief, reflecting the patterns of Charles Ryder’s mind in the tone-colours of Henry Purcell, master, like Evelyn Waugh, of melancholy and the English baroque’. He paid tribute, too, to the directors, the lighting cameraman (Ray Goode) and film editor (Anthony Ham) commanding ‘visions of Oxford, Castle Howard and Venice with the sensual intensity always implied, but rarely stated for fear of empurpling the prose, in the book’.

The Guardian’s Nancy Banks-Smith, while chuffed that ‘those more fortunate than ourselves [are] getting it in the neck’, saw ‘a book of great splendour, splendidly done… one of those occasions when you would like to taste and smell television: the plovers’ eggs, the single peach for luncheon, the ripe white raspberries and the room packed with daffodils. It makes you greedy. I would like to watch the whole thing in one disgusting, 12-hour gulp’. One wonders what the next television adaptation, under Luca Guadagnino, the man behind Call Me by Your Name, will do with that peach.

Clive James, a dedicated Wavian, observed: ‘If Brideshead Revisited is not a great book, it’s so like a great book that many of us, at least while reading it, find it hard to tell the difference.’

Kingsley Amis, for the TLS, and no fan of post-war Waugh, saw a grave defect common to the portrayals of Cordelia, Sebastian and Julia, that in their consonants and vowels ‘they are not nearly posh enough’. But his chief criticism was probably best summed up in the title of his review: ‘How I lived in a very big house and found God.’ He dismissed the Flytes as ‘a band of bores’ (who ‘hang about, idle, rich in an extra sense, given too little to do by the author’.) And as to ‘the drowsy chorus who say the whole thing looks ravishing, well yes but so it bloody should. From the way some of them go on you would think the camera-team had had a hand in building Christ Church or St Mark’s instead of just pointing their instrument in approximately the right direction and remembering to take the cap off the snout.’

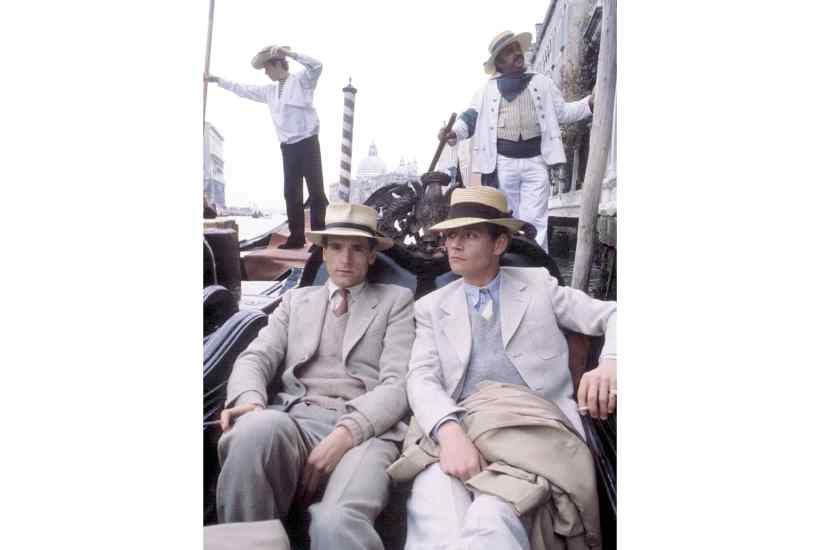

The Spectator’s critics did not disappoint. Richard Ingrams, then this magazine’s television critic, thought it far too long, the characters not nearly strong enough to last the distance. He considered the narration doleful and the music disastrous, ‘too many oboes and horns’. His final grievance was what he saw as the gratuitous ‘gay’ element. ‘Charles and Sebastian sauntered around Venice arm in arm and there was a quite unnecessary shot of naked bums on the Castle Howard roof. No doubt it all looks ever so pretty in colour.’

The magazine’s other legendary contributor and fellow iconoclast — and eldest son of the author — Auberon Waugh, had great fun weighing in on what he dubbed ‘the great Bottoms Debate’: ‘It would be a travesty of the truth to claim that every time Jeremy Irons or Anthony Andrews showed a cheek we opened a bottle of the Croft 1914 at Combe Florey,’ but ‘Certainly my family laughed and cheered at every bare bottom’. He went on to argue that there was a definite homosexual element in the novel but it was written so ‘artfully that it could be read in the drawing room as well as the smoking room’. He put the ‘final bum count’ at eight. What did seem to disturb him as ‘not only distasteful but also highly distressing’ was to have to watch Charles Ryder mauling Diana Quick’s ‘perfectly formed’ nipple as the lovers were being tossed about on the RMS Constantia. He ended with: ‘I think that if ever the Granada contract comes up for renewal, I will insist on that scene being cut.’

Three months after it had begun in Britain, Brideshead was screened by PBS in the United States to even greater acclaim. ‘The biggest British invasion since the Beatles.’ A few critics were perplexed by the enthusiastic reception, which grew to something approaching cult status. But Time magazine pronounced: ‘What distinguishes Brideshead is its sensitive ability to translate the novel’s tone of wistfulness and regret to the screen. Brideshead took a novel and made it into a poem.’

One wonders what the author himself would have thought of this great success. There is the story of the wife of an American theatre producer who told him that Brideshead Revisited was one of the best books she had ever read, to which he had some pleasure in recounting his reply: ‘I thought it was good myself, but now that I know that a vulgar, common American woman like yourself admires it, I am not so sure.’ He affected a similar distaste for television so perhaps, as the Critic’s Alexander Larman suggests, Waugh would have loathed it on principle.

For the rest of us, it remains the sine qua non of mini-series.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Luca Guadagnino’s new BBC/HBO adaptation of Brideshead Revisted will air next year.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in