We have mixed messages on coronavirus: Angela Merkel has said 60-70 per cent of Germans will contract the disease, while the latest data from China and South Korea shows new cases having peaked and, in the case of China, recoveries closing in on new cases.

Aside from spending on health precautions and seeking to staunch the spread, what do governments do?

The Trump Administration is talking about ensuring those thrown out of work are looked after financially – the equivalent of community action in medieval plagues when stricken villages were isolated but fed by those nearby. In a rare flash of economic lucidity, Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer said the government should focus on guaranteeing paid sick leave for infected workers and extending unemployment insurance for people put out of work. But Trump is also urging the Federal Reserve to embark on a financial stimulus.

Australian politicians look likely to avoid panicky measures involving economic stimulus. Hopefully, this means they have learned from past experience. The nation’s senior economist at the time of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, Ken Henry, told Kevin Rudd, always ready to support government spending programs, to “go early, go hard and go consumer”. In doing so Labor destroyed a decade of Howard-Costello budget repair with worthless expenditures that did nothing to restore economic balance. That direction of advice remains popular in an economics fraternity weaned on misplaced Keynesian fears of deficiencies in demand — another former head of Treasury, Martin Parkinson, advocates new stimulus spending.

Instead, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has exorcised his inner Wayne Swan with a focus on maintaining and repairing the economy’s supply capacity rather than boosting demand. He is avoiding cash handouts and the proposal to divert people’s superannuation savings into immediate consumption. Whatever the demerits of the superannuation system, it is an invaluable means of both ensuring people have retirement income and of increasing the level of savings needed for investment. One dark cloud, however, is Reserve Bank, Deputy Governor, Guy Debelle, and his willingness to use monetary measures to provide a stimulus.

The Prime Minister initially announced a fully justifiable $2.4 billion health spending.

The follow-up appears to comprise spending or tax cuts amounting to $17 billion in all. Aside from income support for affected households, It includes $1.3 billion to protect apprentices’ jobs and tax relief for small and medium businesses combined with rapid write off for new investment.

Mad scrambles for toilet paper demonstrate there is no shortage of demand just a shift in it. Clearly, the virus will have drastic effects on air travel and tourism, perhaps also in entertainment and restaurants as well as other activities involving numbers of people in close proximity. But no amount of selective stimulus to these activities will have anything other than a trivial offsetting effect.

On the other hand, there is likely to be a lift in demand for groceries, take-away food and many forms of home entertainment.

While boosting aggregate demand never makes sense, removing barriers that curtail supply capability is always worthwhile. The supply side of the economy is suffering from regulatory distortions to energy, where renewable energy subsidies have brought a doubling of wholesale prices and imposed wasted outlays of around $2 billion a year. In addition, embargos on gas exploration have denied the nation a cheap source of power from abundant reserves. Needless to say, the proposal by Ross Garnaut to use the crisis to throw even more funds at renewable energy would exacerbate the damage already done.

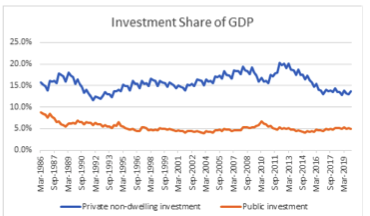

As the chart below shows, Australian investment is also sluggish and its real level is, in any event, exaggerated by the negative value-added that comprises much energy investment. Private investment’s share within GDP has been at under 14 per cent over the past three years, having been almost 18 per cent in the previous five years (public investment averages a declining 5 per cent of GDP). In high growth economies like China investment comprises some 40 per cent of GDP.

In light of Australia’s lacklustre investment, economic growth is unsustainable. The present crisis offers an opportunity to repair the supply side which has taken a battering from poor policies on corporate tax as well as energy.

Alan Moran is with Regulation Economics. His latest book is Climate Change: Treaties and Policies in the Trump Era.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in