It hasn’t been a good week for Brexiteers:

A former Brexit minister and current Conservative MP has been criticised by Britain’s leading Jewish group, and anti-racism campaigners, for using an “anti-Semitic trope” about the spread of “Cultural Marxism” in the UK.

Conservative MP Suella Braverman told a meeting in central London on Tuesday that her party was engaged in “a fight against Cultural Marxism” being led by Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

“As Conservatives, we are engaged in a battle against Cultural Marxism,” she told a meeting of the Bruges Group in Westminster attended by Business Insider.

“I’m very worried about this ongoing creep of Cultural Marxism which has come from Jeremy Corbyn…”

Britain’s leading Jewish group criticised Braverman for using the term.

“Suella Braverman may not have been aware of it, but the term ‘cultural Marxist’ has a history as an anti-Semitic trope,” a spokesperson for the Board of Deputies of British Jews said in a statement.

They added: “We would ask for her to clarify the remarks and undertake not to use the phrase in future.”

The anti-racism group Hope Not Hate was “deeply disturbing” that an MP had used the term.

“This is deeply disturbing and disappointing language to hear from a Conservative MP,” Joe Mulhall, senior researcher at Hope Not Hate, said.

To realise how absurd the situation and how much of a beat-up it is, consider this: the supposed anti-Semitic white supremacist in question is a 40-year old daughter of immigrants from Kenya and Goa (via Mauritius) and she is criticising Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, which actually does have a significant problem with anti-Semitism.

I’m certainly aware that the term “Cultural Marxism” has been used by what can fairly be described as modern neo-Nazi and neo-fascist movements to attack their enemies and in their hands it can definitely have anti-Semitic overtones.

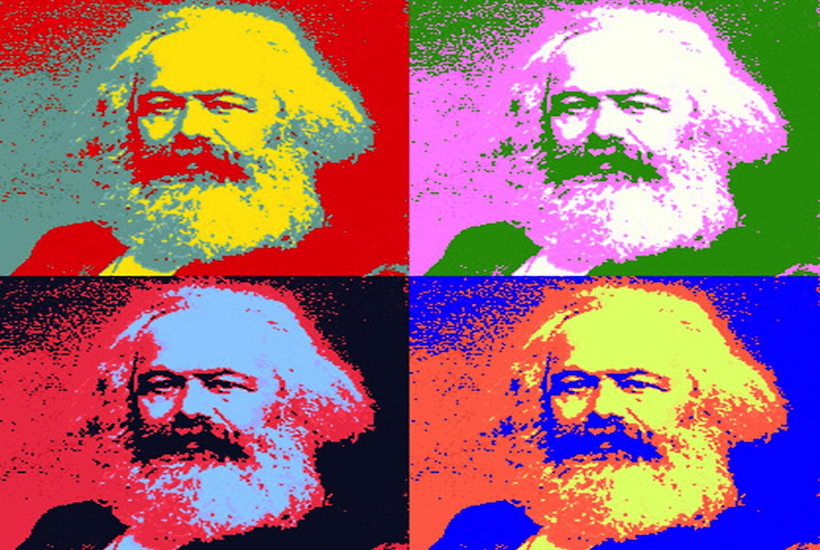

But the problem with describing it as an “anti-Semitic conspiracy theory” is that it obscures more than it reveals – for fascists and Nazis everything is a conspiracy and everything is blamed on the Jews. These people also think that capitalism, liberalism and democracy are similarly Jewish conspiracies. Jews are seen “the devil” in history, the master puppeteers and manipulators, the enemies of mankind (or at least the Aryan mankind), and therefore they are responsible for just about everything that Nazis don’t like. In the case of “Cultural Marxism”, the Jewish connection is the fact that many members of the so called “Frankfurt School” associated with it were of Jewish origins.

For me, the ethnicity of people behind cultural Marxism is completely irrelevant, since I’m concerned about the theory and the practice. But if you are that way inclined, I would suggest that it is essentially an Italian idea developed by Germans.

Furthermore, I don’t consider it a conspiracy theory any more than Marxism or Nazism or any other -ism are a conspiracy theory. Cultural Marxism is simply an idea, an aspect of an ideological program; it neither has been thought up nor has it been implemented by a secret or not so secret cabal. It’s a widespread belief that motivates many disparate people.

As this is not an academic paper but a thumbnail sketch, you will have to excuse my reliance on Wikipedia, but snobbery aside it is as good a source of general information as any.

The origins of cultural Marxism lie in the thinking of an Italian communist Antonio Gramsci (who coincidentally thought his family to be of an Albanian origin):

Hegemony was a term previously used by Marxists such as Vladimir Lenin to denote the political leadership of the working-class in a democratic revolution. Gramsci greatly expanded this concept, developing an acute analysis of how the ruling capitalist class – the bourgeoisie – establishes and maintains its control.

Orthodox Marxism had predicted that socialist revolution was inevitable in capitalist societies. By the early 20th century, no such revolution had occurred in the most advanced nations. Capitalism, it seemed, was more entrenched than ever. Capitalism, Gramsci suggested, maintained control not just through violence and political and economic coercion, but also through ideology. The bourgeoisie developed a hegemonic culture, which propagated its own values and norms so that they became the “common sense” values of all. People in the working-class (and other classes) identified their own good with the good of the bourgeoisie, and helped to maintain the status quo rather than revolting.

To counter the notion that bourgeois values represented “natural” or “normal” values for society, the working class needed to develop a culture of its own. Lenin held that culture was “ancillary” to political objectives, but for Gramsci it was fundamental to the attainment of power that cultural hegemony be achieved first. In Gramsci’s view, a class cannot dominate in modern conditions by merely advancing its own narrow economic interests; neither can it dominate purely through force and coercion. Rather, it must exert intellectual and moral leadership, and make alliances and compromises with a variety of forces. Gramsci calls this union of social forces a “historic bloc”, taking a term from Georges Sorel. This bloc forms the basis of consent to a certain social order, which produces and re-produces the hegemony of the dominant class through a nexus of institutions, social relations, and ideas. In this way, Gramsci’s theory emphasized the importance of the political and ideological superstructure in both maintaining and fracturing relations of the economic base.

Hence, for Gramsci it was as important for the revolutionary class to capture what I call the means of cultural production as to capture the means of (economic) production. Cultural hegemony goes hand in hand with economic hegemony; if you want to remake the society you need to achieve and sustain both. Gramsci’s ideas were indeed further developed by the Frankfurt School:

The works of the Frankfurt School are understood in the context of the intellectual and practical objectives of critical theory. In Traditional and Critical Theory (1937), Max Horkheimer defined critical theory as social critique meant to effect sociologic change and realize intellectual emancipation, by way of enlightenment that is not dogmatic in its assumptions. The purpose of critical theory is to analyze the true significance of the ruling understandings (the dominant ideology) generated in bourgeois society, by showing that the dominant ideology misrepresents how human relations occur in the real world, and how such misrepresentations function to justify and legitimate the domination of people by capitalism.

In the praxis of cultural hegemony, the dominant ideology is a ruling-class narrative story, which explains that what is occurring in society is the norm. Nonetheless, the story told through the ruling understandings conceals as much as it reveals about society, hence, the task of the Frankfurt School was sociological analysis and interpretation of the areas of social-relation that Marx did not discuss in the 19th century — especially in the base and superstructure aspects of a capitalist society.

The actual activist component of cultural Marxism – doing something as opposed to merely contemplating it in university cafeterias – came much later, in the early nineteen-seventies, and it originated with a German (former East German) student radical, Rudolf “Rudi” Dutschke. Dutschke was influenced by both Gramsci and by the Frankfurt School and he interpreted their work on superstructure and cultural hegemony as a springboard for action: “He advocated a ‘long march through the institutions of power’ to create radical change from within government and society by becoming an integral part of the machinery.”

While the Students for Democratic Society’s Marco Savio in 1964 was passionately proclaiming “There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!” Dutschke no longer wanted to throw bodies into gears to make the machine stop; he wanted bodies to start working within the machine to make it eventually work for and not against “the people”.

This strategy, named after Mao’s literal long march from obscurity into the position of ultimate strength, was endorsed by one of the Frankfurt School’s greats, Dutschke’s fellow German, Herbert Marcuse, who wrote:

To extend the base of the student movement, Rudi Dutschke has proposed the strategy of the long march through the institutions: working against the established institutions while working within them, but not simply by ‘boring from within’, rather by ‘doing the job’, learning (how to program and read computers, how to teach at all levels of education, how to use the mass media, how to organize production, how to recognize and eschew planned obsolescence, how to design, et cetera), and at the same time preserving one’s own consciousness in working with others.

“Let me tell you this: that I regard your notion of the ‘long march through the institutions’ as the only effective way…” Marcuse told Dutschke in private correspondence.

The rest, as they say, is history. There is no conspiracy, just a realisation on the part of a significant stream of radicals that culture can be the primary arena of combat for the ultimate political and economic supremacy, rather than a secondary sideshow that Marx had originally considered it; that it’s easier to remake the society once you are in a position to change its values and beliefs, instead of waiting and waiting for the revolution to take control of the means of production.

Hence the growing presence over the past few decades by Marxists or people influenced by Marxism in the academia and the education generally, the media, entertainment industry, bureaucracy, community sector and other opinion and values making and shaping institutions.

If around half of today’s young people proclaim support for socialism (while not really knowing what it means) you have largely the influence of education and popular culture to thank – or curse – for it.

Culture matters. The left has realised it much sooner than the right, and with a long headstart and experience they are doing much better at fighting for it and claiming it than the right. To fight against the cultural Marxism is not to engage in conspiracy mongering against a phantom Jewish menace but to struggle for over the ideas, values and beliefs that shape our society.

I’m not going to cede the terminology to neo-Nazis any more than am I going to surrender to Marxism is any shape or form, and least of all because the left – as has been the case for almost a century now – tries to equate and conflate the opposition to its agenda with extremist tendencies.

“Doctors’ wives” isn’t the perfect expression, but it makes a very clear point. So does “cultural Marxism”.

And unlike “doctors’ wives”, it’s more than a metaphor.

Arthur Chrenkoff blogs at The Daily Chrenk, where this piece also appears.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in