It was in his organ loft at Arnstadt that I began my acquaintance with Johann Sebastian Bach — with JSB, with the young man, with the writer, the fighter, the lover. After the great walk of his in 1705 that we would follow, and after his return trek in February 1706, he would be caught at it in that organ loft with a ‘mysterious’ woman, who may or may not have been she who became his wife. It is the perfect place for a stolen moment. The church is now white and golden, and wooden, ugly on the outside and elegant as a cream bun on the in. To reach the loft you leave the producer talking to the stern and understandably suspicious woman in moral charge of the church — who are these English people?

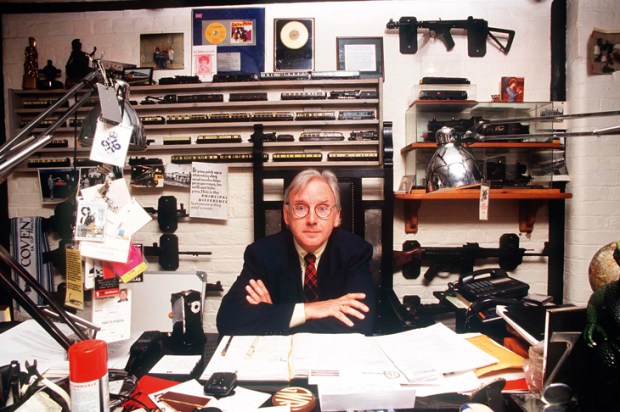

Richard Andrews, studio manager, was recording seven tracks, or five but one of them was double. His hand-built rig is the state-of-the-art equipment for recording three-dimensional 360 degree wildtrack (ambient sound), my voice, as I walked 20 yards ahead of him, and his footsteps, every one of them, on the five expeditions we judged most likely to have followed Bach’s paths of 1705. In late October of that year the fighting, womanising young man who was and would become J.S. Bach walked the 280 miles or so from Arnstadt to Lübeck to see and hear Dietrich Buxtehude, the organist in charge of St Mary’s church, the Marienkirche, there.

Atop all the staircases is an angled-loft ladder barred by a low locked gate. Hop over this and you are soon in the nest, the ceiling low, the scent woody and the organ for all the world a steampunk supercomputer in its wooden housing. It has been replaced severally since Bach’s machine. Our Radio 3 producer, Lindsay Kemp, pointed out that in that era an organ would have been the most complex and miraculous machine for miles around. Bach would have tested it, as the family businesses of music and organ-minding had taught him, by pulling out all the stops and hitting all the keys. The noise produced told him the builders had not cheated Arnstadt by making some of the inaccessible pipes not out of lead, but cheaper tin. It was a good new organ he controlled, and he had a good salary too, and friends and family proud and on hand for miles around… and yet. Johann Sebastian was a young man to take the rough with the smooth and call it decent fortune. He was laconic and unimpressed by authority in general, and when someone irritated him he called them out, loudly and cuttingly. He branded an inept musician named Geyersbach ‘a prick of a basoonist’. Geyersbach lay in wait for Bach in the Marktplatz, and when Bach came by accosted him with some ruffian friends and struck the genius-to-be in the face with a cudgel. JSB went armed. He drew his dagger and fought his assailants. Geyersbach later produced a garment bearing, he said, cuts from Bach’s strikes. It seems unlikely to have been the truth, although we can be sure Johann Sebastian was dexterous.

There comes a time in the lives of most interesting young people when someone in authority agrees with alacrity that he or she should take some time away. Four weeks’ leave, they said. JSB packed his sack — money, paper, ink, pen, a change of clothes and a cloak against the rain, we reckon — and went. He went for four months. Up yours, burghers! Bach had things he wanted to explore, things he wanted to know, things Buxtehude could teach or show him. We have so few of his actual words from this period. It was a bit like ghost-hunting Shakespeare by walking and recording the old paths between Stratford and London, with slim evidence beyond dates and direction of travel. ‘Some things about his craft and art,’ was his given reason for wanting to meet Buxtehude. He knew his target gave Sunday evening recitals, as well as the day-to-day composing and playing and conducting they all did. I bet he could hardly wait, as he set out. If you tune in to our series of programmes about the walk, you will hear that I had the same condition on the first day. I was over-excited, walking quite quickly, commenting and commentating on every bird box and Alsatian we passed.

By the second day — a trek up the Harz mountains to the once Soviet spy-infested peak of Brocken — I had calmed down. The mist and the strangeness of the mountains, with the hoots of steam trains swirling and echoing through the gloom, called for more walking and more thinking. We made a great discovery that day. No way did Bach walk around the base of the one significant geographical feature of his route. It would have added days, and the Harz mountains are not really mountains, not like Snowdonia, say. They are big ridges, what they call hills in South Wales, with a dramatic crown, and lynxes. The road would have been rich all the way with inns and offers of accommodation. He went over the Harz, I am quite sure. It is a dramatic and easy walk.

Lindsay, with his maps, his recce — he had done all our walks in the preceding weeks — and the Germanically wonderful level of signage all along the route, should have struggled to get us lost. On the third day he made it look effortless. We are standing in a dripping wood, trying not to curse or giggle, and failing. Richard is patiently fitting unlubricated condoms over a battery of microphones he has taken out of their hairy Rycote cover. He also carries hairbrushes to keep them fluffy, or they mat and lose their power to silence the wind. Lindsay is turning his map around again and occasionally muttering. I am smoking and I think drinking — as a professional travel writer I take a hip flask, thankfully, for, despite arailway and a river running in the same direction as our mission, we are lost.

Having grown up on Radio 4, then Massive Attack, the Stone Roses and Cypress Hill, I was not expecting to get nearly as close to Bach as we did. Now he is not just the composer of the cello suites, which at his age I came to love and know. He is another writer, crossing one of the most fascinating countries in the world at a time of post-strife and pre-drama analogous in many ways to our own. He has an eye for a woman, a goldcrest, a million beech trees. He hears and absorbs the cart wheel clip-clop and woodcutter’s axe-tok, the voices and glasses of the inns.

I am quite sure that the walk and the encounter in Lübeck with Buxtehude made him who he became. As the Prophet Muhammad grew up on camel caravans, as the early British elite with their sewn-plank boat expeditions in the late Neolithic took their chief’s son along as crew, to grow him — so travel made him, I believe. You can judge for yourself, when we get to Lübeck on the 45-minute Christmas Eve programme, how close we might have come to Johann Sebastian Bach.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in