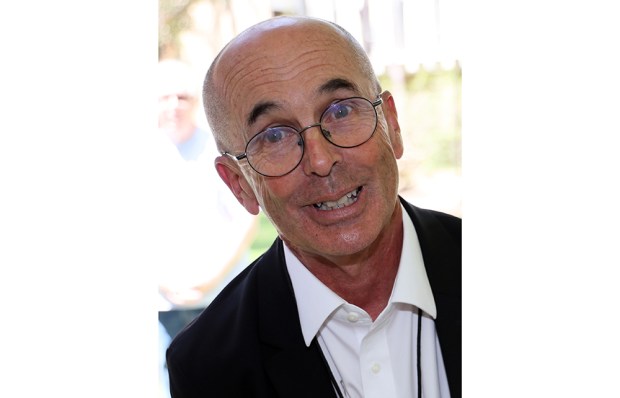

When it comes to Bob Dylan, Clinton Heylin is The Man Who Knows Too Much. Since publishing his first biography, 1991’s Behind the Shades, he has become the world’s most committed Dylanologist, doggedly untwining the facts from the artist’s self-serving fictions. When he describes Dylan’s wildly unreliable 2004 memoir Chronicles: Volume One as ‘all a put-on… all a lie’, he has the receipts. As he never tires of pointing out, scholars and diehards are in his debt, but amassing data from sessions, setlists and now 130 boxes of Dylan’s formerly private papers is not the same as telling a good story. For someone innocently hoping to understand one of the cultural giants of the last century, the reading experience might resemble drinking from a firehose.

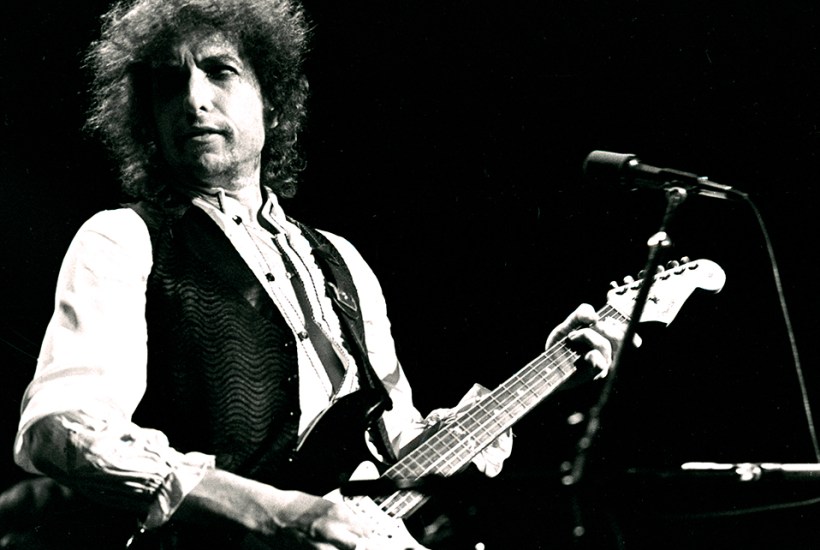

Heylin’s first volume left the 25-year-old Dylan recovering from his famous motorcycle accident in July 1966, at the height of his celebrity. The former folk prodigy had not just exploded the parameters of rock songwriting but become a reluctant prophet, besieged by questions and demands. He turned paranoid and peevish: harder to know and impossible to understand. ‘I noticed how obsequious people were when they were in Bob’s presence,’ his former mistress Faridi McFree tells Heylin. ‘Therefore, Bob never really trusted anyone.’ Perhaps this is why he seems somehow incomplete as a person. The great book editor Robert Gottlieb found the middle-aged Dylan to be ‘almost childlike – you felt he barely knew how to tie his shoes, let alone write a cheque’. Joni Mitchell suggests one reason why he hasn’t stopped touring since 1988: ‘He’d rather play music probably than do anything else. He doesn’t relate to people.’

Heylin loves Dylan but I’m not sure he likes him. There are strikingly few tales of generosity or warmth here and much evidence to the contrary. Heylin excels on the chaotic stretch of Dylan’s career which casual fans skip over. In 1978, having experienced a religious vision in a hotel room, the singer became obsessed with the Book of Revelation and the mega-selling crank eschatology of Hal Lindsey. He appeared to be mutating into the Reverend Jerry Falwell, telling audiences that Armageddon was imminent, that ‘Satan has infested the rock’n’roll world’ and that San Francisco was ‘a dwelling place for homosexuals’. Ever the spiky contrarian, Heylin considers the 1979-80 hellfire tour ‘probably the best shows Dylan ever gave’ while disdaining 1997’s widely celebrated comeback album Time Out of Mind (‘a mess’) and almost everything he’s done since.

Sex was another component of Dylan’s almighty midlife crisis. He confessed to Lauren Bacall (a pleasingly unlikely friend) that he was a ‘disaster when it comes to women’, and one can see why. His infidelities put paid to his 13-year marriage to Sara Lownds (immortalised in 1975’s Blood on the Tracks) and he was ruthlessly fickle with subsequent lovers. As he told the playwright Sam Shepard: ‘You gravitate toward people who’ve got somethin’ to give you… And then maybe one day you wake up and see that they’re not given’ it to you any more.’ He was also something of a misogynist. ‘I hate to see chicks perform,’ he told Rolling Stone in 1987. ‘Hate it. Because they whore themselves. Especially the ones that don’t wear anything. They whore themselves.’ Rolling Stone omitted that quote. Heylin, to his credit, does not.

This came during the ‘four-year-long lost weekend’ which took Dylan to the brink of quitting music. The temporary collapse of his talent terrified him because he is not a tenacious craftsman like Leonard Cohen or Nick Cave. As he describes it, the songs come and go, like a supernatural visitation over which he has no control. ‘He doesn’t like to think too much about anything, because he thinks it’ll break the spell,’ observes his friend and erstwhile producer Dave Stewart. Therefore, never analyse, never explain.

In such sections Heylin’s exhaustive research pays off, but many of these pages are tough going. Chapters arrive burdened with as many as 12 epigraphs while the ceaseless footnotes are the trenches in which Heylin wages his bitter forever war against rival Dylanologists who have committed such unforgivable sins as misdating recording sessions. His prose can be gratingly waggish (Paris becomes ‘gay Paris’; multiple sentences begin with the word ‘’Twas’) and jaw-droppingly crass (a black woman is a ‘duskier dame’), with a weakness for fan-tickling in-jokes. Your tolerance for lines such as ‘The Caribbean wind still howled, even if the distant ship of liberty had been hijacked by a jokerman wearing a disguise’ may vary.

‘These so-called connoisseurs of Bob Dylan music,’ Dylan once said, ‘I don’t feel they know a thing, or have an inkling of who I am and what I’m about.’ Most fans have given up trying to know; they’re just grateful that he’s still alive and working at 82. Heylin, however, remains on the case. He reminds me of Nicholas Branch, the historian in Don DeLillo’s Libra, whose secret history of the JFK assassination will never be finished because the ‘data-spew’ never ends. ‘There is nothing in the room he can discard as irrelevant or out-of-date,’ DeLillo writes. ‘It all matters on one level or another. This is the room of lonely facts. The stuff keeps coming.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in