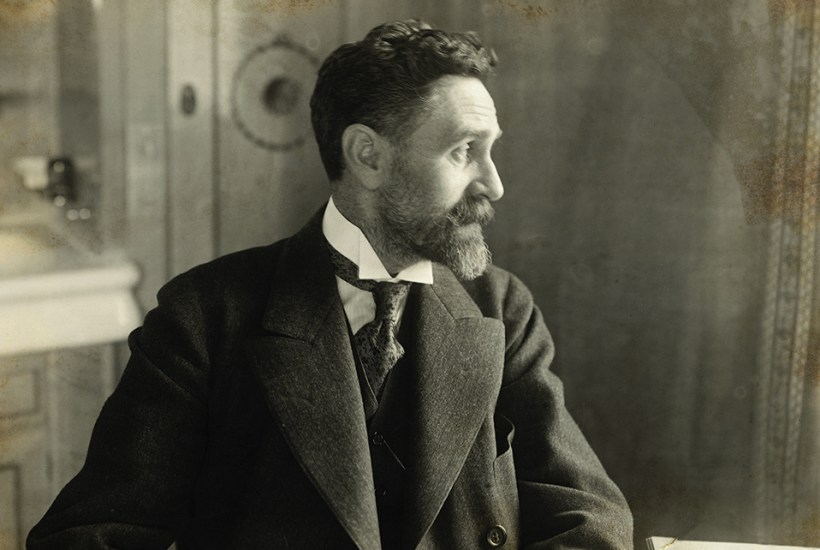

Telling the story of Sir Roger Casement’s life is a challenge for any biographer. In the land of his birth, he is remembered as a national hero. His remains lie in the Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin beside the graves of Daniel O’Connell and Charles Stewart Parnell. He is there because he was hanged in Pentonville Prison in August 1916 as one of the leaders of the Easter Rising.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in