One thing that exasperated me intensely during my many years as an opera critic was the assumption that I must be a passionate admirer of Maria Callas. She is the only prima donna who most people have heard of, and her supreme status has long been taken for granted, to the point at which the sound of her voice, as well as her personal story, have fomented a myth, a legend, an icon, and made any rational judgment almost impossible. She is Callas, La Divina, the embodiment of opera: one can only fall down and worship.

In a year that marks the centenary of her birth (she died in 1977), the incense in the temple has become positively stifling. Marina Abramovic is currently in London, en route with an international tour of her opera 7 Deaths of Maria Callas. The Diva exhibition at the V&A has Callas at its heart, and there are further shows of Callas memorabilia on offer in Paris, Milan, New York and Athens. A new movie about her, directed by Pablo Larrain and starring Angelina Jolie, is in the pipeline; one hopes it will be less toe-curlingly awful than its precursor, Callas Forever, with Fanny Ardant in the title role. Terrence McNally’s play Master Class, about Callas’s brief attempt to teach, continues to be hugely popular globally, and Meryl Streep and Faye Dunaway have been associated with as yet unrealised filmed versions.

All this on top of a Callas bibliography that runs, according to the British Library catalogue, to 136 books, let alone the countless reissues and remasterings of her recordings that must have sold in their millions. For hard facts, I can only recommend Tom Volf’s documentary Maria by Callas (available on DVD), which assembles much of the surviving footage and allows the story to be told in her own words.

Why the obsession? I suppose the fundamental appeal is the idea of a woman with a remarkable talent who made a terrible mess of her life. Perhaps we can all sympathise with that, but nobody ever points out how the biographical evidence paints a picture of someone who was also her own worst enemy, cursed with what her recording producer Walter Legge called ‘a superhuman inferiority complex’, toxically combined with an overwhelming sense of her self-importance that made her both arrogant and paranoid – and pretty unpleasant to boot.

If she was a victim, then she was as much the victim of her own ruthless self-centredness and vindictiveness as any wrong done to her. Violent in temper, she brutally ghosted her mother and sister, left a trail of corpses among friends and colleagues, and deserted her stolid husband for Aristotle Onassis, a crook with nothing to recommend him except a shedload of money. Far from being dedicated to her art, she was ready to sacrifice it to ‘a stupid ambition’, as Franco Zeffirelli put it, to be ‘a great lady of café society’, in imitation of her style model Audrey Hepburn. One searches through the literature in vain for any redeeming feature – small kindnesses or consideration of anyone except herself. A home movie of her on holiday in the last months of her life, uncovered by Tom Volf’s documentary, shows her lounging by a swimming pool, bored, solitary, listless and joyless, without any inner resources – a figure of pathos, but not of tragedy.

One might argue that the question of Callas ‘the woman’ is irrelevant, but I think it has become inextricable from the question of Callas’s genius as a performer, and the way that the black, doom-laden timbre of her voice – instantly recognisable and similar to that of grandmothers shouting at each other across the squares of Greek villages – suggests a force of character that was constantly pushing itself beyond its natural capacities. No wonder that she burnt out so soon, almost self-destructively. By the age of 35, she was on a downward trajectory, developing a heavy vibrato, a rasping lower register and unreliable intonation above the stave.

Five years later, she was dried out and had effectively retired. By the time she turned 50, a moment when most great singers comfortably sit in their prime, she made a desperate attempt at a comeback that resulted in humiliation. I was there at the Royal Festival Hall in November 1973, and can recall how raw and colourless she sounded, her confidence shot to pieces, even though she only had to contend with piano accompaniment and a few carefully tailored highlights devoid of potentially embarrassing top notes.

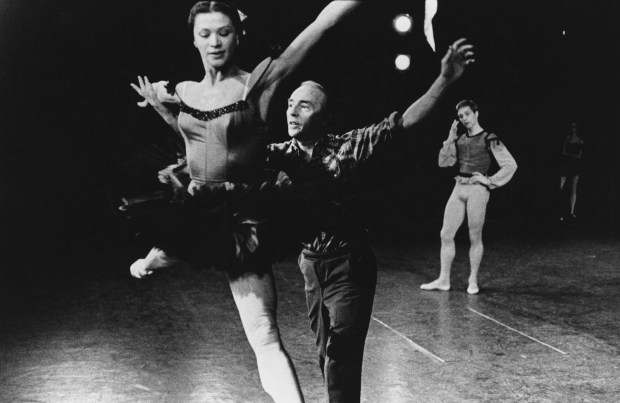

Of course, there were great things in her career. She had a marvellous ability to sculpt the grand architecture of a phrase, to seize a dramatic moment and hit the emotional solar plexus. I think of her enthralling first studio recording of Tosca, for example, or the crackling electricity she generates as Lady Macbeth, Anna Bolena and Medea on pirate tapes made live at La Scala. What little was filmed of her on stage also suggests her ability to regally command an audience’s attention – call it ‘charisma’ if you like. But this was the result of instinct rather than intellect: in the televised interviews with Lord Harewood and the master classes she gave in New York in 1971-2, her insights do not rise above banalities.

So please, can we have a moratorium? I’ve heard more than enough of Callas’s ‘Vissi d’arte’ and ‘Casta diva’. I’m bored of tales of her martyrdom, and the legacies of her less prized contemporaries have so much to offer. For sheer beauty of voice, there’s Leontyne Price and Montserrat Caballé; for pure legato and smoothness of tone, Renata Tebaldi; for the intense nuanced colouring of words, Renata Scotto. Listen to them, and then we can return to Callas and make a more judicious assessment of her achievement.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in