Pity Arts Council England, least loved of our NGOs, understaffed and under-resourced, its arm’s-length status gnawed to the shoulder by DCMS ukases, the stinginess of the Treasury and the government’s (in some respects, welcome) indifference to our higher culture.

In return for its annual grant-in-aid (currently £336 million), it is obliged to cheer-lead policies of inclusivity and diversity and step gingerly over the eggshells of elitism, racism, gender politics and decolonisation.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

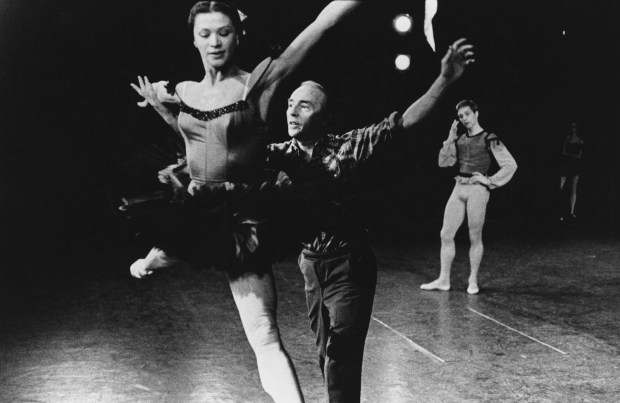

ENO opens its season with a new production of Tosca on 30 September at the Coliseum. ENB’s Swan Lake starts on 28 September at the Liverpool Empire.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in