Roxy Music didn’t make Phil Manzanera rich. Kanye West did. When a guitar phrase from Manzanera’s obscure 1978 solo song, ‘K-Scope’, was sampled in 2012 by West and Jay-Z on their track, ‘No Church in the Wild’, the one-third share Manzanera was given of publishing and sales revenue proved life-changing. The song featured on a platinum-selling album, and was used in The Great Gatsby and numerous adverts. ‘I would earn more money from a short guitar riff that I wrote one evening on a sofa in front of the telly than I ever earned in the entire 50 years as a member of Roxy Music.’

‘My dad had a habit of turning up in countries just ahead of their revolution’

Prior to the West windfall, Manzanera was hardly on his uppers: he’d experienced the standard industry rites of poor management and dodgy deals. These days he seems to be doing all right. I’m chatting to him via Zoom from his home in West Sussex, where his nearest neighbour is David Gilmour, though it’s not possible to wave a greeting at the Pink Floyd singer across a lovingly creosoted garden fence. ‘David lives next door,’ he smiles. ‘When I say next door, it’s about ten minutes’ drive away…’

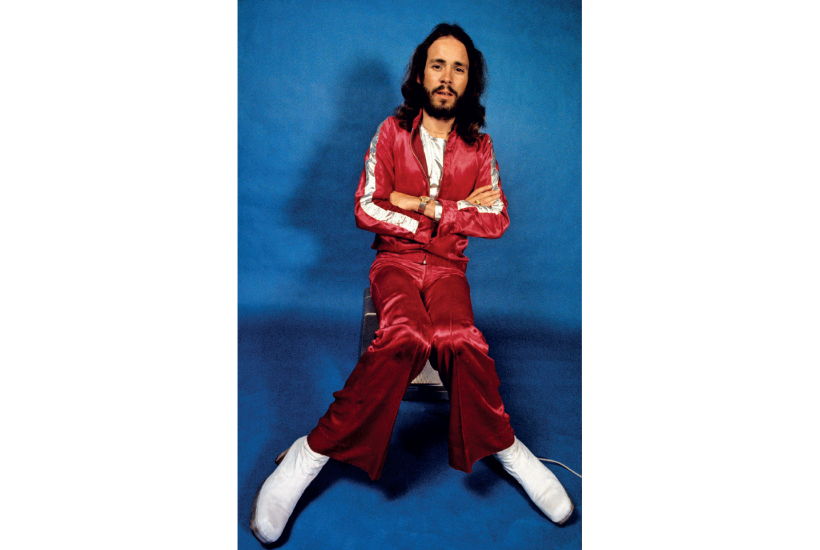

As the guitarist in Roxy Music from their eponymous debut album in 1972 to their farewell shows in 2022, Manzanera played beautifully skewed, cumbia-inflected rock guitar on all those classic songs: ‘Virginia Plain’, ‘Do the Strand’, ‘Love is the Drug’, ‘More Than This’. When Bryan Ferry was off chasing solo stardom, Manzanera did his own thing, continuing an alliance with his former Roxy foil Brian Eno on several projects, reforming his school band, Quiet Sun, making solo albums, producing, curating, collaborating. The list of close associates – Eno, John Cale, Robert Wyatt, Gilmour – reads like a Who’s Who of British innovators, a group to which he comfortably belongs.

He’s tricky to pin down. A former Dulwich College pupil whose fees were paid by the local authority, he’s fluent in English and Spanish and can lay claim to three identities. Manzanera is the maiden name of his late Colombian mother and the one, you suspect, he identifies with most closely. His paternal family name is Targett-Adams – or so he thought, until the recent discovery that his father had been born illegitimately outside of his grandmother’s unhappy marriage, fathered in a Hastings boarding house by a Neapolitan opera singer. So, really, I am interviewing Philip Sparano.

Little wonder his amiable memoir, Revolución to Roxy, casts Manzanera, 73, as a windblown troubadour. ‘People have said that it reads more like a 17th-century novel, like Don Quixote, than a music book, because it’s this series of adventures on my circuitous journey without any particular destination. I’m pleased about that. It’s as if I’m Forrest Gump – I seem to land in all these interesting places.’

Long before Manzanera was a rock star, his father worked for the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), setting up new offices around the world for the airline. The family moved from Clapham to Cuba, then to Hawaii and Caracas. They were living in Havana when Fidel Castro’s revolutionary troops entered the city early in 1959, heralding the end of Fulgencio Batista’s military regime. Aged seven, at two in the morning, Manzanera recalls ‘machine gun fire all around us, lying on the floor in the bathroom, pressed down by my mum’. One of Batista’s top generals, Francisco Tabernilla, was a close neighbour. As dawn broke, two trucks containing Castro’s ‘Barbudos’ pulled up outside the house in fatigues and sealed off the whole street. Twenty of Tabernilla’s guards were lined up and led away. Shots rang out. The general escaped, but his home was looted.

While his distraught mother was keeping her children safe, Manzanera suspects his father, Duncan Targett-Adams, was working for British intelligence. BOAC was the government’s airline and, as Manzanera points out, ‘he had a habit of turning up in countries just ahead of their revolution’. He was due to receive an OBE when he died, prematurely, in 1966. ‘He had people working for him who were part of Fidel’s people in Havana, apparently. When he wrote Our Man in Havana, Graham Greene was in a hotel 100 yards from my dad’s office. Greene was MI6. My best friend was British Consul. Before he died, I showed him a picture of my dad and some others. I asked: “Who are these people?” He said: “Spooks, spooks.” There was something going on.’

After Havana, the family moved to Hawaii, then Venezuela, whence Manzanera was despatched to Dulwich College, a guitar-playing boarder with the 1960s on his doorstep. ‘Growing up, I wanted to be in a band,’ he says. ‘For a lot of my early childhood, I was the only sibling around. I wanted company. With Roxy Music, I thought I was joining a band like the Beatles, not in terms of artistic merit, but camaraderie. I bought into the idea of the Beatles being the Four Musketeers. There was definitely lots of fun and laughter in Roxy, but it wasn’t really a band like that. It was a collective.’

Early on, Roxy Music pivoted around the two Bri/yans: Eno and Ferry. Each brought a distinct aesthetic vision. ‘Bryan studied fine art. Eno went to art school, but his tutor was the same guy who taught Pete Townshend. He’s way out there in a totally different kind of art world. He was a “non-musician” who brought conceptual ideas. I don’t come from that art world at all, so how do I fit in? I’m primitive, autodidactic, just trying to make sense of what we’re up to. We weren’t technically incredibly proficient, but the combination of all our little bits created this textural world which Bryan could inhabit.’ Manzanera felt ‘all at sea’ when Eno left Roxy Music in 1973 – the creative tensions between him and Ferry exacerbated by ‘an undercurrent involving someone else’s girlfriend’ – but Roxy Music regrouped and went on to make many more fine records, with Manzanera having greater involvement in the writing process. You can see why someone might grow tired of working with Ferry. Even the mild-mannered Manzanera was irked by the singer’s high-handedness, making big decisions without consultation, bringing in outside musicians with no prior warning. By the early 1980s, he felt like a session player in his own band.

I wonder whether there is a more unknowable rock star than Ferry; the Durham miner’s son turned urbane socialite who never quite comes into focus. ‘The funny thing is that both he and Eno are the same people they were when I met them,’ says Manzanera. ‘It’s not as though fame has changed them. Bryan wants to create something beautiful, and he’s meticulous. He’s an artist. I get it now. I didn’t really get it before. It’s nothing personal. If you’re a painter or you studied art, being in a band is a weirdly artificial thing. You don’t get Picasso and Miro working together; they would kill each other instantly! They were all solo artists, those boys. This ‘band’ idea created in the 1960s is quite a strange phenomenon. But I’m proud of what we achieved in Roxy. It seems to have some lasting legacy. We did our farewell tour, but the name, the brand, seems intact.’

‘Ferry’s meticulous. He’s an artist. I get it now. I didn’t really get it before’

Revolución to Roxy is no kiss-and-tell. Manzanera ‘didn’t want to settle scores or go into too much detail about things that would upset people’. As for drug-fuelled debauchery: ‘It’s all in other people’s books. I thought, we’ve read all that before, what’s the point?’ There are some pleasing titbits, however, including a scene from the band’s 2001 re-formation in which a packed press conference is severely delayed because the band is in a suite upstairs haggling over each member’s split of the lucre.

Rather than chasing money, Manzanera has generally been more concerned with maintaining control of the means of production; perhaps some of the Castro spirit seeped in. He has his own studio and label. His book is self-published and he doesn’t have a manager. ‘I’ve been indie in 90 per cent of everything I do. The whole point of being a musician was to be free, not to be told what to do.’

Though he has enjoyed the process of summoning the past, he isn’t contemplating a career change. Books versus music? No contest. ‘What tends to happen with books is that people read them once – maybe twice, but probably once. How lucky are we as musicians? We wrote some song 50 years ago in ten minutes and spent a day or two recording it, and people are still listening.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in