The lengthy process to find a more permanent home for Australia’s low-level nuclear waste has likely received its last rites this week with the Federal Court upholding a complaint from the Barngarla people about the process at Napandee, on South Australia’s west coast.

The nearby town, Kimba, lays claim to being ‘halfway across Australia’ and while it is a small community, it exhibits the spirit of many small towns in this country – a willingness to give things a go and to seize an opportunity where it presents itself.

To counter the tired cliché of activists who insist that ‘you wouldn’t want it in your backyard!’ local MP Rowan Ramsey said he’d be happy to store it on his own farm in the area. While a sitting MP couldn’t nominate as part of the process, a number of local farming families saw the opportunity to create new employment and reinvigorate their community during a time of population decline. One family’s nomination of their freehold land to the Commonwealth kicked off a comprehensive process of community consultation, including with traditional owners.

The impetus for the disposal of Australia’s nuclear waste is the nuclear facility at Lucas Heights in Sydney. During its life, it has provided nuclear medicine products for millions of people and in the process, created around 5,000 cubic metres of nuclear waste. To deal with this waste and other deposits stored in over 100 locations around the country, several governments have proposed different solutions for a more permanent facility. The need to complete this process is becoming more pressing as the site will begin to reach capacity in 2028.

The judgment from Justice Charlesworth on Tuesday, July 18, raises the spectre of several concerning effects. The first is that it effectively calls into question the notion that freehold land extinguishes Native Title, meaning that even if you own the land, if you want to use it for something that the ‘traditional’ owners dislike, they can obstruct the owners (or in this case, the federal government) from doing so, using the instrument of the Federal Court.

The Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation opposed the Napandee site on the grounds that they were denied the right to vote in the community ballot on the proposal in the Kimba District Council area. Due to none of the applicants being registered as residents or ratepayers in the region, they were rightfully denied a ballot. The vote returned a 61 per cent yes vote, which is a convincing result in any terms. The Barngarla subsequently conducted their own vote, resulting in 83 of the 209 eligible participants voting yes demonstrating that there is not unanimity among Aboriginal people on the issue.

The second issue this judgement raises is that of veracity of claims. The owners of Napandee had been farming the land since they purchased it over a decade ago and don’t recall any requests from traditional owners to visit sacred areas or for any other purpose. In fact, Native Title was applied for in 1996 and granted in 2015 and when assessing the site, the National Radioactive Waste Management Facility found that Native Title was extinguished and ‘no sites registered on the central Archive Register of Aboriginal Sites were identified…’

As the Hindmarsh Island Bridge debacle proved, there should be a threshold for allowing heritage concerns to overrule progress. The mere suggestion of heritage should not be enough to impede the development of a project that has been approved by a Minister following a departmental approval process. Similar to debates on the Voice, even daring to question the existence or authenticity of sacred sites immediately cues the shrill cry of racism.

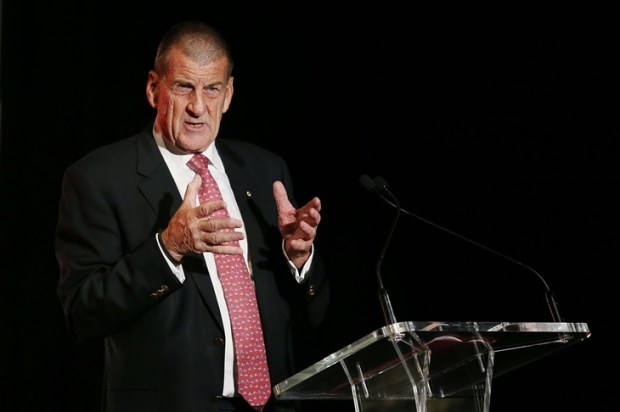

The final issue is that of how much ministerial due diligence is enough. Justice Charlesworth found that (then) Minister Keith Pitt was biased in his approval of the Napandee site. How could the Minister find differently after years of community consultation and a community ballot? Not to mention the millions of taxpayer dollars to reach this point. The decision was clearly not made in haste, given the level of consultation and investment.

Further, the legislation permitted Ministerial approval on this matter. The subtle creep of delegated legislation is not something that would typically be advocated in these pages; however, this was the way the Napandee decision was to be made. To suggest that the process is wrong because you don’t agree with the outcome undermines the ability of Ministers to sign off on anything.

The only recourse left to keep the project alive is for the federal government to challenge the finding. While it is unlikely to do so when it is struggling to sell the Voice to ordinary Australians, it should, to ensure an activist minority cannot apply a handbrake to the entire community.