‘Photography has arrived at a point where it is capable of liberating painting from all literature, from the anecdote, and even from the subject. So shouldn’t painters profit from their newly acquired liberty, and make use of it to do other things?’ argued Picasso. The inventor of cubism took advantage of his liberty in ‘Buste de Femme’ (1938) to turn Dora Maar into a precursor of Peppa Pig, flaring her nostrils to form a snout. Perhaps he wanted to teach a photographer a lesson about paint by rubbing her nose in it.

Picasso didn’t abandon the subject or the anecdote. He was one of the first modern artists to turn a news event into a painting – Maar compared ‘Guernica’ to ‘an immense photograph’ – and the contemporary artists in Tate Modern’s new show focusing on the relationship between photography and painting have piled in after him. Some have even riffled the same news sources: Marlene Dumas in her painting ‘Stern’ (2004) recycles the same magazine shot of the dead Ulrike Meinhof used by Gerhard Richter in an earlier series of paintings from 1988, like two vultures picking over the same corpse.

For postmodern painters, the photographic source has become a sort of fetish. Richter has claimed that ‘the most banal amateur photograph is more beautiful than the most beautiful painting by Cézanne’, but his paintings from his own photographs are not. There’s something slickly synthetic about a Richter landscape like ‘Scheune’ (1984) with its foreground brushwork mimicking the indecisive blur of the lens. Not unnaturally, these pictures look better in photographic reproduction; in the flesh, they’re icky.

German painters take themselves awfully seriously, photographers likewise: the scale of the prints by Düsseldorf School photographers Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth and Candida Höfer in a ‘Photography as Painting’ room is portentous. Apart from Dorothea Lange’s unforgettable image of a ‘Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California’ (1936, printed c.1950), capturing the moment in an 11x8in frame, all the photographs in this show are ‘grandes machines’. The paintings, too, bar the Picassos, Bacons and Freuds in the opening room, are all bigger than they need be, huge canvases designed for the walls of museums and billionaire collectors – in this case Taiwanese electronics magnate Pierre Chen, who has put his Yageo Foundation collection at Tate’s disposal to mount this loosely themed and rather haphazard show.

Anyone expecting decisive moments à la Cartier-Bresson will be disappointed; a better title for the show would be ‘catching the zeitgeist’. There are good things in it. The high point, for me, was seeing Jeff Wall’s ‘A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai)’ (1993) in the flesh, having previously only admired it in reproduction.

Wall took a year and more than 100 shots to create his photographic riff on Hokusai’s woodblock print and has made something startlingly contemporary out of it. Hokusai’s travellers have an old-fashioned sense of purpose as they struggle against the wind down a winding track hanging on to their bamboo hats, but Wall’s buffeted figures, clapping their baseball caps to their heads, seem directionless and confused. Their blunderings are rendered almost balletic, but that’s nothing when compared with the choreography of the windblown papers escaping from the office worker’s folder, which trace a dance pattern through the sky meticulously mapped out in the accompanying study, each numbered sheet carefully taped in position.

Trained as a painter, Wall draws an interesting historical distinction between photography, ‘based in that sense of instantaneousness’, and traditional painting, which ‘created a complex and beautiful illusion of instantaneousness’. Both sorts of instantaneousness are in short supply here. There are hints of the beautiful illusion sort in Peter Doig’s ‘Canoe Lake’ (1997), but only David Hockney, in his ‘Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)’ (1972), really pulls it off. In an exhibition low on élan vital, this unashamedly feelgood image by the Bradford boy made good, living the Californian dream, is a lift to the spirits. Everything about the painting is executed with minimum frills and maximum effectiveness: the golden net of refracted light cast on the water, the pointilliste colour in the background hills. Pitched exactly halfway between the photographic and the painted image, nothing in the show comes close to it.

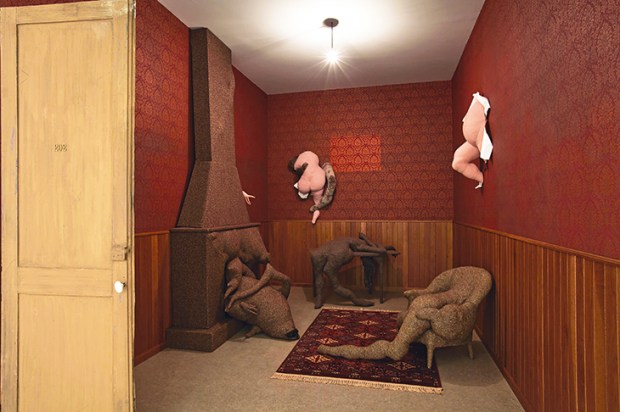

Can this balance be maintained in the digital age? In his digital paintings Hockney has lost it, but a new generation offers hope for the future. In ‘9PM, the News’ (2015) in the final room (see above), Salman Toor switches between visual languages with the ease of a simultaneous translator, making the paint do whatever he wants: give naked flesh the finish of grainy newsprint, splash cartoon flashes and splats across the picture surface, mimic red chalk drawings. Born in Pakistan in 1983 and living in the US, he describes his painting as ‘a process of self-definition, as an outsider in multiple worlds which become more and more entangled and complex’. The fact that his viewpoint is personal is what makes it engaging; too much of the photo-based work in this show is impersonal and cold.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in