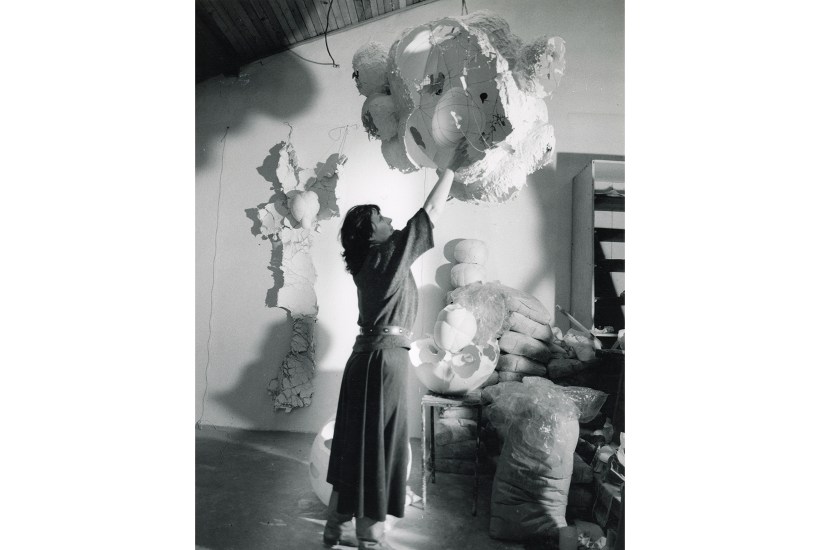

Art is a fundamentally childish activity: painters dream up images and sculptors play with stuff. It was while playing with an inflatable ball with her young daughter in the early 1960s that Maria Bartuszova had the idea of filling balloons with liquid plaster instead of air. The inspiration fed her muse for 30 years, seeding the mixed crop of biomorphic forms currently filling five rooms at Tate Modern.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in