Later this year, over two million Muslims will travel to Mecca, Islam’s holiest city, for the Hajj, one the five pillars of Islam. Yet the historical basis for the Meccan pilgrimage is far from clear. During Muhammad’s lifetime, Mecca was literally off the map for most of the world. No pre-Islamic source so much as mentions its existence, despite the contemporary interest in the region. A number of Roman historians provide detailed descriptions of western and southern Arabia, yet did not make so much as a single mention of Mecca. On this basis alone we are reasonably safe in concluding that, contrary to Islamic tradition, Mecca was at the beginning of the seventh century a relatively minor, isolated settlement in the arid deserts of western Arabia. It was not well integrated with the broader worlds of the ancient Mediterranean and Mesopotamia.

With such scarce natural resources available, it is truly hard to imagine that Mecca could sustain a very large population in Muhammad’s lifetime

The Islamic historical tradition claims to know a lot about pre-Islamic Mecca. Yet scholars of early Islam have long recognised that these much later memories of Muhammad’s Mecca are not historically reliable and cannot be taken at face value. These canonical narratives about the beginnings of Islam are instead pious reminiscences, which have little if any connection with the actual events of the seventh century or the history of ancient Arabia. Profound scepticism of these accounts is necessary, since they were composed extremely late. With only few exceptions, all of the Islamic historical tradition’s detailed narratives about the central Hijaz during the early seventh century were first recorded at least 100 years, if not many more, after the fact. Considering no pre-Islamic literature survives from this region, we are left with practically nothing to go on.

We may, however, discern some basic things about Muhammad’s Mecca based on climate and geography, which do not seem to have changed much since the early seventh century. Mecca lies in an extremely arid and hot desert region. It is not in a location capable of sustaining either a large population or extensive agriculture. It sits in a valley surrounded by high barren mountains, with extremely limited natural water sources, and only a few brackish wells and a small spring. It was, as one scholar tersely observed, ‘devoid of food and other amenities that human beings and other animals generally require to engage in activities of any kind.’ With such scarce natural resources available, it is truly hard to imagine that Mecca could sustain a very large population in Muhammad’s lifetime. Indeed, a recent study has convincingly determined that the likely number of total inhabitants in Mecca at this time was around 500 or so, with only around 130 free adult men.

Nevertheless, according to much modern scholarship, during Muhammad’s lifetime Mecca was a wealthy place, with a vibrant economy based on long-distance, high-value trade. Certainly, given Mecca’s small size and its extremely poor natural resources, some sort of a trade seems quite likely, even necessary. Lying in a remote desert among barren rocks, Mecca’s location could not support any agriculture at all, and its inhabitants must have made their living herding goats and sheep: little else would have been possible. Only through some sort of exchange, then, could its citizens eke out a difficult and spare existence. Without the ability to trade for basic foodstuffs to keep the community alive, Mecca simply could not have existed. So, its inhabitants must have traded something for food in order to survive – the only question is what?

For most of the twentieth century, scholars of early Islam held fast to an orientalist myth of Muhammad’s Mecca as the financial centre of a vast international trading empire that trafficked in luxury goods. Mecca, they imagined, was the hub of a lucrative network of spice and incense trade coming northward from the south of Arabia and points beyond to the east. As these high-value commodities passed through Mecca on their way to the Mediterranean world, so it was supposed, Mecca’s inhabitants grew wealthy by brokering the exchange of these luxury goods.

At the nexus of this vast financial empire was the Quraysh tribe, which Muhammad belonged to. This was the dominant tribe in pre-Islamic Mecca according to later Islamic tradition. Muhammad’s Mecca is therefore envisaged as an important cultural and financial centre. It is as if something resembling modern Dubai was conjured out of the barren desert of late ancient Arabia by scholars in order to provide an appealing backdrop for the emergence of Muhammad’s new religious movement.

But the evidence paints a very different picture. To be sure, the Meccans traded. They had to since, left on its own, Mecca could not provide enough food to feed even its meagre population. But Mecca was no centre of major international trade in luxury goods and spices. Indeed, if we look to the actual evidence for trade in spices and incense from ancient South Arabia (and India) to the Mediterranean world, this scholarly mirage of Mecca as a wealthy financial centre quickly dissolves. Trade between the Mediterranean world and South Arabia and beyond had been well established and had been for many centuries by the time Muhammad was born. Yet from the first century AD onwards all such trade was conducted by sea rather than overland. The latter was a slower, more expensive, and more dangerous option.

It is true that the Meccans had a very small port available to them on the coast some 40 miles to the west of the settlement. But they had no timber and, accordingly, no seagoing vessels. And you cannot reasonably imagine that seafaring traders would have reached this tiny port and travelled 40 miles across the desert just to visit – for whatever reason – the remote and barren village of Mecca. Moreover, the port itself, now the site of modern Jedda, was in antiquity blocked by a large reef and could not receive ships of the size necessary for long distance trade. At best it may have been used by a few small fishing boats, if at all.

Even the Islamic historical tradition tells us that this location first came into use as a port only well after Muhammad’s death. Muhammad’s Mecca, therefore, was certainly not a wealthy centre of international trade in spices and perfume. By all indications, in late antiquity international trade bypassed this small, impoverished, remote desert settlement. Mecca’s trade was instead both modest and local, involving the exchange of goods from its subsistence pastoralist economy for desperately needed foodstuffs and other supplies from larger agricultural settlements nearby.

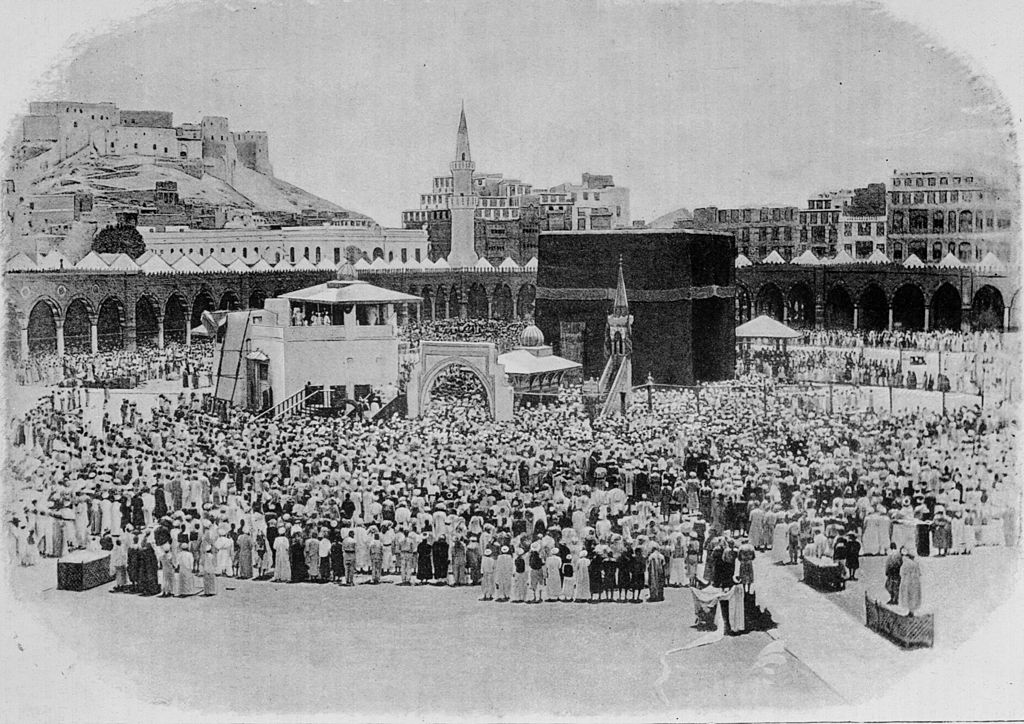

Mecca, 1889 (photo: Getty)

Mecca, 1889 (photo: Getty)

In addition to trade in high-value luxury goods, modern scholars have also proposed that Mecca derived considerable wealth and status from its possession of a major pilgrimage shrine. Supposedly this shrine drew visitors from every corner of Arabia to Mecca each year, who brought with them commerce, further enriching Mecca as part a major pilgrim fair. The presence of this shrine would have afforded Mecca the status of a ḥarām, an inviolable religious sanctuary wherein no violence or bloodshed was allowed. Accordingly, many modern scholars have proposed that Mecca’s shrine and its sanctuary status were instrumental in its emergence as a major centre of international trade in luxury goods. Mecca’s protected precincts offered a safe place for merchants to gather and trade without fear of molestation, bringing visitors year-round to exchange their wares, many of whom settled into the city along with their wealth. Nevertheless, it turns out that this image of Mecca as a major pilgrimage centre and an inviolable religious sanctuary is no less of a myth than the Meccan spice trade.

The Islamic historical tradition, which is really our only source for knowledge of such matters, gives no indication that Mecca was the site of any pilgrimage before the rise of Islam, with or without any sort of corresponding trade fair. Yet the early Islamic tradition is not otherwise silent regarding pre-Islamic pilgrimages and pilgrim fairs in general, and it identifies several religious sanctuaries (ḥarāms) that hosted such events, some of which are not far from Mecca.

Moreover, all of the most important events of the traditional Islamic pilgrimage, the hajj, actually take place outside of Mecca, several miles from the city itself, with the climax coming at Mount Arafat, roughly 12 miles east of the city. This is significant, since modern scholars widely agree that the traditional Islamic pilgrimage most likely mirrors and incorporates pre-Islamic practices, a point on which the Islamic tradition also agrees. Yet if the traditional Islamic pilgrimage has its basis in older Arabian religious practices, then this tells us something important about ancient Mecca.

The fact that all of the most significant events of the hajj take place well outside of Mecca offers a strong if not compelling indication that any pre-Islamic pilgrimage observed in this region did not involve the city of Mecca itself. In all the discussions of these ancient rituals in the early Islamic sources, Mecca consistently appears almost as an afterthought, if at all.

The Islamic tradition itself belies the existence of any pilgrimage or religious sanctuary in Mecca before the rise of Islam. Mecca’s eventual incorporation into the traditional rites of the hajj as a kind of launching and landing pad for the pilgrimage proper appears to be a secondary, post-Islamic development introduced most likely in the later seventh century. Adding Mecca and its ‘Holy House,’ now the black cube of the Ka’ba, as a stop before and after the pilgrimage was an important way to put a clear Islamic stamp on these older ‘pagan’ rites. Having the pilgrimage commence and conclude in the city where Muhammad first began to receive his revelations and organise a new monotheist community made clear to all that these rites were in no way ‘pagan’ but instead thoroughly monotheist and Islamic in nature.

We might ask, then, was there any religious shrine at all in pre-Islamic Mecca? It is hard to say with any certainty, and if there was, it certainly was not the Ka’ba in its present form, which is from the later seventh century. It does seem reasonable to suppose that the herdsmen of this small remote settlement and their families would have had some sort of local sacred shrine that they revered. Yet there is little chance that a minor, village shrine would have held any significance beyond Mecca’s 500 or so inhabitants and perhaps some nearby nomads. There is also no reason to suppose that it was the focus of any sort of major pilgrimage, or the cause of an inviolable sanctuary, or the impetus for an economy based in high value international trading. Rather, ancient Mecca was by all measures a remote, hardscrabble place whose nonliterate, pastoralist inhabitants must have been quite isolated from the broader worlds of Mediterranean and Mesopotamian late antiquity.

These cultural and economic limitations obviously raise profound questions about the traditional linkage of a text as sophisticated as the Qur’an with a sleepy hamlet such as Muhammad’s Mecca. The Qur’an’s content demands an audience steeped in the traditions of ancient Judaism and Christianity. How would the goatherds of Mecca have possessed the level of religious literacy required to understand the Qur’an’s persistent and elliptic invocations of Jewish and Christian lore? There is, moreover, no evidence of any significant Christian presence anywhere remotely near Mecca: the closest known community was over 500 miles distant.

Clearly there must be more to the Qur’an’s origins than the later Islamic tradition has remembered, since Muhammad’s Mecca (or his Medina for that matter) simply does not seem capable of having produced such a highly cosmopolitan religious text. In order to understand the Qur’an’s formation, it seems we must look beyond Mecca and Medina, despite what the Islamic tradition tells us.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in