Last month the Productivity Commission (PC) revealed that Australian productivity growth on the decade to 2020 was the lowest in 60 years. Mining and agriculture were the most efficient sectors, though productivity gains in some services – like medicine and digital services – may be hidden because of improved quality.

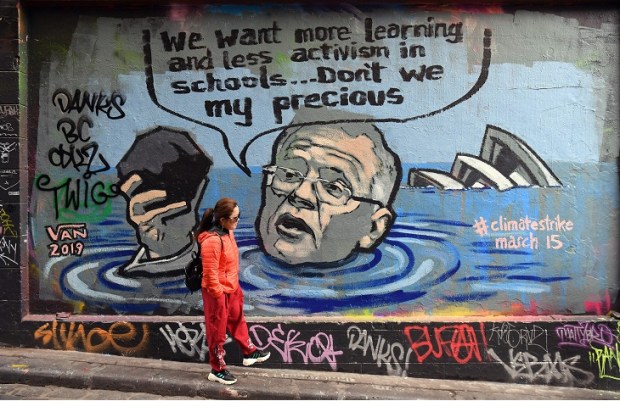

To avoid antagonising the dominant political ideology, with masterly understatement, the PC opines, ‘…(carbon dioxide) abatement efforts could, in many instances, increase the cost of production and could put downward pressure on measured productivity, at least in the short term.’ The PC makes stacks of recommendations for improvement, including some that could raise productivity by freeing up investment and work from regulations; few of those will be taken up.

The outlook is even worse than the PC envisages. Attacks on the ‘gig’ economy, higher taxation, and greater regulatory intrusions are the hallmarks of the present ALP governments in Canberra and elsewhere on the mainland. And the key to productivity growth – high investment – is flagging even more radically than in the decade to 2020.

New private capital expenditure in 2022 was some $110 billion. It had grown rapidly in the first decade of the 21st century before falling markedly after 2012. And, though recovering from a Covid low, it remains almost 30 per cent below the level of its 2012 peak.

But while Sol may be right in saying ‘oils is oils’, not all investment is equally productive. Firms’ capital spending on items forced by regulation or subsidised by government would fail to pass the value thresholds of expenditure driven by the search for profit in a market without government intervention.

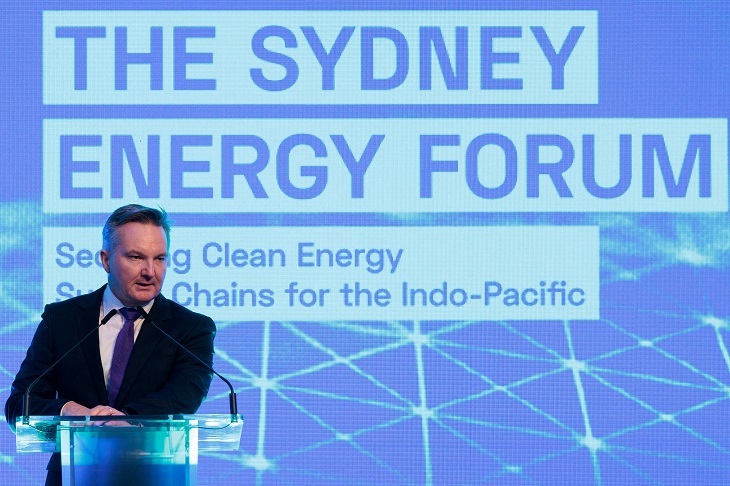

Thus, the value of the private investment in recent years is much reduced because it includes a growing component of renewable energy and associated expenditures, all of which is reliant on government support. According to Bloomberg, private capital expenditure on renewable energy amounted to over $17 billion in 2022. This is to enable the ‘transition’ to wind/solar generated electricity that is inherently more expensive and unreliable than gas and coal which provides two-thirds of existing supplies.

Not only is the replacement energy more expensive but it forces lower cost coal generators to close because the subsidised wind/solar can offer negative prices and, because of the government assistance they receive, still make a profit. These intermittent weather and daylight-dependent renewable sources squeeze out intrinsically lower cost coal and gas.

The subsidies to wind and solar amount to some $7 billion a year, which is equivalent to over half the total wholesale cost of electricity prior to the subsidy-powered growth of renewable supplies displacing cheaper coal and gas. (The Australian Financial Review oddly claims that the ‘political carbon wars in Canberra means there has been no market-based investment signal to drive the fastest, most efficient and lowest-cost energy transition’.)

At $17 billion a year, spending on renewables, which was quite small ten years ago, now constitutes over 10 per cent of total private capital expenditure. Not only does this detract from the quantity available to lift productivity but, like a cancer, it eats away the existing stock of capital.

Because the subsidised wind and solar is intrinsically more costly, wholesale prices have risen. They have done so without any assistance from the Ukraine war. Wholesale electricity prices were under $50 per MWh in 2015 before the closure of the first major coal stations, Hazelwood in Victoria and the Northern Power Station in South Australia. Wholesale prices are now $112 per MWh. This week’s full closure of the Liddell station in New South Wales will cause another upward ratcheting of prices. That prospect, and the associated higher risks of blackouts, has panicked the incoming NSW government. While unable to prevent the scheduled closure of Liddell, the Minns government is seeking ways to prevent the giant Eraring station’s closure, nominally scheduled for two years from now.

All this has repercussions on productivity. Economies like Japan, followed by China and India, grew very rapidly because their governments put in place the low tax policies with low regulatory barriers. As a result, they experience a virtuous circle with increased domestic savings which supplied funds for increased private investment.

Australia is moving in the opposite direction, calling forth higher taxes. Private investment is falling and an increasing portion of available capital is being attracted to subsidised wind/solar electricity supply facilities. Not only are these inefficient but they actually undermine the economics of existing generation plant. They compound this by requiring considerable additional investment expenditure on transmission lines to gather the dispersed and low-density power that flows from wind and solar generators.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in