Imagine a folk dance without music. Actually, you don’t have to: poke about on YouTube and you’ll find footage from 1912 (there’s music dubbed on, but it’s a silent film) of Vaughan Williams’s friend George Butterworth in full Morris fig, going through the moves with Cecil Sharp and a pair of pinafore-wearing gals. Note the precision of his movements, that big Kitchener moustache: how seriously Butterworth is taking it, four years before he stopped a bullet on the Somme. And they really were sincere, those folk song pioneers. The same modernising impulse drove Bartok on his song-collecting journeys at the opposite end of Europe, and in 1913 – two weeks after the première of Le Sacre du printemps – Sharp’s Morris side gave demonstration performances to an avant-garde crowd in Paris.

Still, I would not have predicted that the most striking moment in a recent Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra concert under Andrew Manze would come from The Running Set, a six-minute squib that Vaughan Williams wrote in 1934 for an international folk dance festival in London. ‘The Running Set’ was also a folk dance without music. Sharp encountered it in Kentucky and detected English roots in the traditional moves, while noting that the original melodies had been lost.

Vaughan Williams duly filled the gap, and if nothing sounds more disturbingly redolent of the 1930s than mass folk dance at the Royal Albert Hall, wait until you hear the piece. It snaps brusquely into action, and – at least as conducted by Manze – bounds forward with a breathless, kinetic energy. VW includes a piano in the orchestra, doubtless as a practical aid for amateur performances, but nothing springs an orchestral sonority into the 20th century like a piano and it flashed and stabbed its way through the texture like chrome-toothed steel. Meanwhile, the violins fitted a streamlined casing over the spinning, driving jig rhythms. It was a miniature rite of a very English spring: a short ride in a steam-powered machine, and to be honest, I did not see that coming.

The Running Set was included in this concert in preparation for a recording: part of Manze’s ongoing series of Vaughan Williams discs with the RLPO, of which he is the principal guest conductor. And no bad thing, either: the Vaughan Williams anniversary year has been noticeably short on major rediscoveries. Where were the headline Proms performances of Dona Nobis Pacem or Sancta Civitas? Why no revivals of Riders to the Sea or The Pilgrim’s Progress? Only the reconstructed Scott of the Antarctic film score seems to have brought anything really new to the party – more on that, hopefully, in a few weeks’ time.

But one notable recent development has been the (overdue) acclamation of the Fifth Symphony as a cherished national classic, featuring (in an organ transcription) in the funeral of the late Queen, and toppling even Elgar in an online poll. Manze finished the concert with the Fifth, in a measured, eloquent reading that opened huge hazy vistas inside the Philharmonic Hall. The great ‘Alleluia’ key change at the summit of the Preludio generated the requisite shivers. And at the end of the Romanza, and again at the conclusion of the whole symphony, Manze drew playing of such honeyed, delicate sweetness from the RLPO string section that it felt as if the symphony were expiring in sheer bliss: less transcendence than a spirit of pure benediction. The recording gives only a hint of its sensuous beauty.

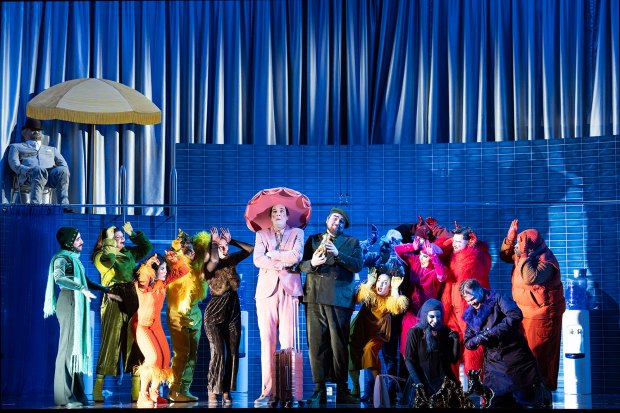

I had expected to write a lot more about Christof Loy’s new Tosca at English National Opera, but really, it doesn’t need much description. It’s basically a straight, period-appropriate Tosca, attractively designed, and directed for the most part with humanity and theatrical flair. Loy does have one slightly eccentric idea – ghostly figures in 18th-century costume stalk about the stage to emphasise the contrast between Scarpia’s repressive ancien régime and the free spirit and vaguely modern costumes of Cavaradossi (Adam Smith), Angelotti (Msimelelo Mbali) and Sinead Campbell-Wallace’s naive, youthful Floria Tosca. Smith spent the opening scene of Act Three in a prison cell – a slightly clumsy imposition.

But overall, Loy’s Tosca hits all the right beats, and (spoiler alert) Tosca’s final leap is one of the most convincing that I’ve ever seen. What an actor, indeed! Due to vocal problems, Noel Bouley mimed the role of Scarpia on this second night of the run, while Roland Wood sang, magnificently, from the side. But Smith and Campbell-Wallace were both on glorious voice, rolling it out in long, impassioned lines and easily cresting the swell of Leo Hussain’s ardent, oceanic conducting. With performances like these, this a Tosca worthy of the West End and you can book with confidence, either now (it runs all month) or for the many revivals that Loy’s production will surely receive over the next few years.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in