On the train home from the Royal Festival Hall I learned of the death of Michael Tanner, who wrote this column from 1996 to 2014 and beyond. The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment had been playing Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony, and it’s not strictly true to say that the news made me wonder about his likely reaction to their performance, had he been able to hear it. But that’s only because, for anyone who came of age reading his criticism, asking ‘What would Michael say?’ is already a reflex – and will be for as long as we think or write about music.

There was plenty to interrogate here, not least that an orchestra founded to give historically informed performances of music from (the clue’s in the name) the 18th century was playing a symphony completed after the first world war. It’s not a wholly new development. Some British period instrument groups have tiptoed up to 1914 and then, as a rule, retreated. Certainly, none have embraced late romantic repertoire as vigorously or successfully as François-Xavier Roth’s extraordinary French ensemble Les Siècles, which plays Stravinsky ballets and Ravel operas on period instruments, to ravishing effect.

Could the fascination of hearing the textures of this symphony clarified and softened like this – the surprise at hearing timpani rattle rather than rumble; the way Sibelius’s cross-hatch string writing becomes a charcoal sketch rather than a linocut – outweigh reservations about Maxim Emelyanychev’s volatile conducting? Emelyanychev has made the transition from hot young prospect to much-loved fixture almost imperceptibly. The players grinned as he bounced

them through the opening movement of Grieg’s first Peer Gynt suite (yes – that serene, once-famous ‘Morning Mood’) at a lilting dance tempo.

Again, stifle the inner voice that mutters darkly about the purpose of ‘authenticity’, and which dimly recalls reading that there was only one bassoonist in Norway in the 1870s, and that he wasn’t very good. (The OAE’s bassoons were ripe and delicious.) I wasn’t convinced by the way Emelyanychev and the OAE played their encore, Grieg’s ‘Last Spring’, but I loved them for playing it. And so heart defeated head, in extra time, though any worthwhile artistic experience should bring both into play. Michael – like the philosopher he was – unerringly identified and asked the awkward questions, but always as a means of opening up one’s response to a work or performance. He invited and relished contradiction.

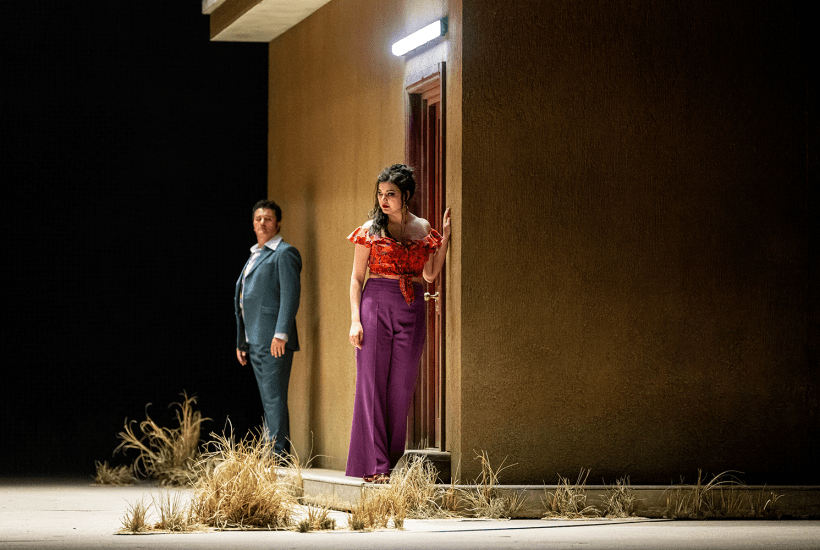

Take the last time he reviewed Carmen – Barrie Kosky’s 2018 Covent Garden staging, now junked after two revivals. His observation that there are only two real characters in the opera points you to the core of what the director of this new production, Damiano Michieletto, is attempting with two of the others, Escamillo (Kostas Smoriginas) and Micaëla (Olga Kulchynska). Clearly, he’s trying to fill them out – but while Smoriginas sang handsomely and projected sufficient self-consciousness to make him a plausible minor celeb, Michieletto’s characterisation of Micaëla overshoots by a mile. As a potential rival to Carmen (Aigul Akhmetshina) she’s basically Velma from Scooby-Doo: a bespectacled girl-geek wearing a sack. Game over in scene one.

It’s set in the early 1980s, by the way, and all you really need to know is that Piotr Beczala sings in chiselled phrases as Don José (more a frustrated junior manager than a slave to passion) and that there’s smoke as well as fire to Akhmetshina’s Carmen. She’s also unabashedly sexy, which counts as a negative in Carmen these days. Antonello Manacorda conducts with purpose and makes the score soar as well as dance, even if the final scene didn’t fully land its punches. In a touch of pure Wes Anderson, Michieletto has the children’s chorus trot on during the entr’actes carrying captions in French. The audience loved that.

For the rest, this is Carmen by numbers: a catalogue of every possible cliché associated with updatings of this opera. Dusty Spanish badlands? Check. Sleazy cops? Check. Huge bullfight billboard, neon-lit strip joint, white Transit van? Check, check, yawn. Regardless, the Royal Opera is currently the only full-scale game in town.

ENO concluded its season with just two performances of what was billed as a concert version of Bela Bartok’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle but which was in fact a resourceful and visually striking staging by Joe Hill-Gibbins with conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya drawing yearning, shot-silk sonorities from the ENO orchestra.

On the first night, the Judith was indisposed so Jennifer Johnston sang the part with searchlight intensity, standing on stage while the staff director Crispin Lord gamely mimed the role. For a full hour, John Relyea (a heroic, jet-toned Bluebeard) addressed his pride and pain to a bloke in a frock.

If ENO wasn’t in such a wretched plight, it might have seemed comic. But in truth, both the company and this impressive production deserved better luck. Let’s hope they get it, and soon.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in