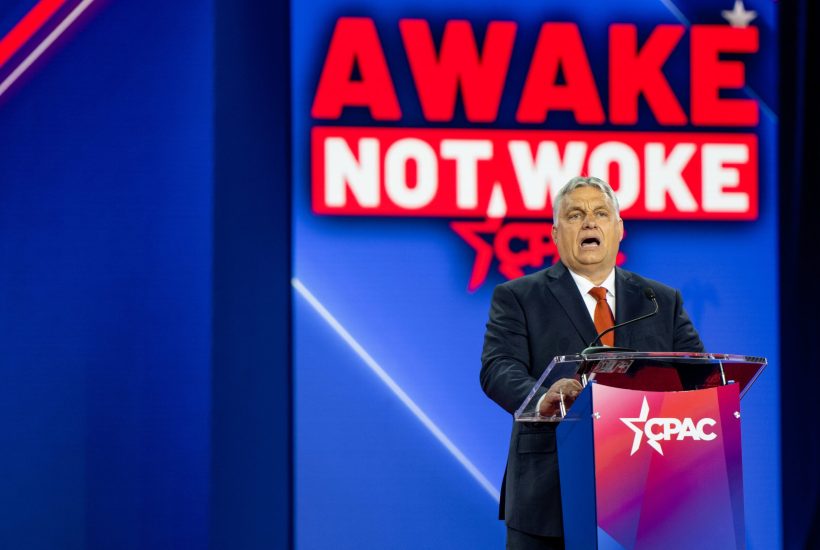

Say what you want about Viktor Orbán, but he gives a good speech. His address on Thursday in Dallas on the opening day of CPAC, the annual jamboree of the American right wing, was wide-ranging, hard-hitting and quite funny. One of his best jokes – paraphrasing Pope Francis – was ‘that Hungary was the official language of heaven because it takes an eternity to learn’. It also happens to be nonsense. Hungarian is recognised as considerably easier to learn than Arabic or Mandarin, but Orbán doesn’t do nuance. In fact, the entirety of his speech was about drawing an unbridgeable distinction between the ‘Judeao-Christian’ values of himself and his audience on one side, and the ‘progressives liberals’ and ‘woke globalist Goliath’ on the other.

Predictably, Orbán reeled off a carefully curated list of his government’s achievements: lower taxes, support for families, a focus on law and order, and the elimination of illegal migration by building a wall along Hungary’s southern border. He also delighted his audience by lauding the values of the ‘lone star state’, praising Donald Trump and Ronald Reagan, and throwing in references to cultural heroes like Clint Eastwood and Chuck Norris, as well as mentioning Texas’s famed Rangers the Ewing Oil Company. He insisted that the Republican party could emulate his own success in winning four straight elections, as long as they refused to compromise. The forthcoming elections in both America and Hungary were ‘two fronts in the battle for western civilisation’, he said: a line that went down particularly well.

But amidst the bombast Orbán also subtly challenged his audience. In contrast to some on the American right’s proposals to ban abortion outright, Hungary continues to permit abortions up to 12 weeks (or later if the child or mother’s health is in danger). Nevertheless, Orbán observed that his government’s subsidies had, in the past ten years, doubled the number of marriages, and halved the number of terminated pregnancies. Likewise, though he called on America to negotiate with Putin, he condemned ‘the attack of Russia against Ukraine’, a line that has become slightly gauche for some conservatives.

Orbán wisely avoided any repetition of his recent denunciations of a ‘mixed race world’ and the ‘flooding of the West’ by migrants, which prompted a long-term ally to resign. He insisted that Hungary has a ‘zero-tolerance policy on racism and anti-semitism’ and instead focused his ire on ‘illegal migration’ while noting that anyone could apply for asylum at a Hungarian embassy.

The cynics see Orbán as a culture war fighter trying to distract people from a slowing economy. They’re wrong. His rhetoric isn’t the stuff of modern culture wars – it is part of the Hungarian political tradition. Orbán’s belief that the West is irredeemably decadent and in cultural decline follows previous conservative criticisms of liberalism. Right-wing Hungarians, especially clergymen, were vocal in denouncing the new consensus at the end of the nineteenth century. Likewise, earlier revolts against Habsburg rule were inspired by a Christian nationalism which became the dominant ideology in the interwar period. This messianic hostility to foreign influence appeared progressive when it was directed against the conservative Habsburgs, and reactionary when it rejected the abolition of the monarchy and universal suffrage as foreign imports after 1918. It inspired Hungarian revolutionaries against Stalinist rule in 1956, and was dismissed as an embarrassment thereafter, only to be rejuvenated by the economic, social and moral crisis that engulfed the country after the fall of communism in 1989. Orbán, who entered politics as an idealistic liberal, rebranded himself as the standard bearer of this Christian nationalism after his confidence-shattering defeat in the 2002 elections. He has hardly looked back, winning four votes on the trot since 2010.

Nevertheless, Orbán still presides over an awkward coalition bound together as much by electoral successes as by ideological coherence. His cabinet includes cautious moderates such as his respected finance minister, Mihály Varga, in post since 2013, as well as radicals such as Péter Szijjártó, who has served as foreign minister since 2014 and received an Order of Friendship from his Russian counterpart. The extent to which Orbán will turn his rhetorical attacks on the ‘eggheads of the European Union’ into concrete policies remains uncertain.

For now, Orbán is an idol for conservatives worldwide. Chastised and traduced by his liberal opponents, he has consistently outlasted them, becoming not just an ideological hero, but an electoral one too. As he took to the stage in Texas, he could hardly contain a wry smile.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in