Stepping into the Sistine Chapel, the choir loft is probably the last thing you’d notice. ‘Loft’ is, frankly, a stretch for what amounts to a small alcove with a wooden bench, carved out of the chapel’s wall. But if you made your way up there and ran your hand over the stone you’d feel something unexpected.

Etched into the wall in haphazard graffiti are hundreds of names. In most cases the carvings are all that remain of centuries of singers from the papal choir. But one is different: ‘JOSQUINJ’. Chances are it’s the only surviving signature of Josquin des Prez — a composer whose name and legacy are carved just as deeply into the history of music itself.

This August marks the 500th anniversary of Josquin’s death. We celebrate it because the year of his birth (like so much about the composer) remains frustratingly uncertain. His name (which appears in endless variations), nationality, even his music comes tinged with doubt, thanks to unscrupulous publishers passing off imitations as the real thing. One wag famously observed that Josquin had composed more since his death than he ever had in life.

What we do know is that Josquin changed the course of musical history. Not for nothing has he been compared to Virgil, Copernicus. He inherited the angular choral style of the late Middle Ages and softened its sharp gothic points, stripped away the jagged buttresses of its outer voices, and revealed music of new evenness and classical order — music in which spiritual perfection was not just imitated but enacted. As no less a figure than Martin Luther observed: ‘Other composers must follow what the notes dictate. [Josquin] is the master of the notes, which must do as he wishes.’

So why don’t we hear more of his music today? The answer’s a long one, but boils down to two reasons. The first is that, for all our modish talk of cultural ‘disruption’ and ‘transgression’, we still feel real discomfort when faced with historical art that blurs the lines. Josquin is the master of musical piety — just listen to his Inviolata, integra et casta es or Ave Maria…Virgo Serena, whose echoing lines fall through the voices like the weightless, translucent folds of Strazza’s ‘The Veiled Virgin’. But he’s also bawdy, erotic, vulgar.

That might be okay if it were limited to secular chansons like ‘El Grillo’ with its frotting rhythms, or the thrusting, repetitive desire of ‘Allegez moy’, usually translated as ‘Relieve Me’ but which could be rendered more accurately with a four-letter verb. But, as with so many artists of the era, this bawdiness follows him back into sacred repertoire — a persistent undercurrent of secularity that adds a frisson to a work like the Stabat Mater, whose tenor part quotes Binchois’s ‘Comme femme desconfortée’. The lament of a woman abandoned by her lover is transformed, but never quite concealed, in the despair of the Virgin for her dying son. What are we supposed to make of that?

The second argument is more straightforward. Josquin isn’t a Palestrina or a Tallis who gives it all up at a first listen. Intricately mathematical constructions underpin works that come to life under the analyst’s microscope, but which can seem forbidding for an audience — an intricate game for performers that risks shutting out anyone without the musical password. There’s no quick fix for that, just a promise that — like the cathedrals it was written for — the music is no less awesome because it needs time and multiple vantage points to reveal its secrets.

In this anniversary year we’re spoilt for choice when it comes to Josquin. A new recording from Stile Antico offers a handy beginner’s guide, while the Tallis Scholars’ 34-year project to record all the composer’s 18 masses is the more involved option (the latest volume comes stamped with some prestigious awards). There will be Proms performances this summer, as well as concerts by all the usual choral suspects. But, meanwhile, English Touring Opera’s latest and quirkiest digital offering is a provocative starting point.

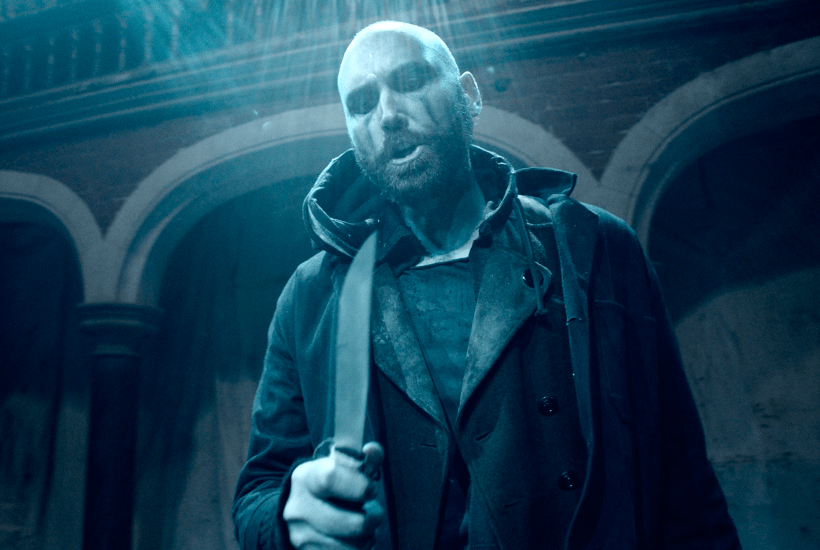

Six of the composer’s works — secular and sacred — are staged in a half-hour film that strings the pieces into a theatrical, quasi-narrative sequence. Filmed in a shadowy Welsh chapel (cleverly lit by David Kidd), the aesthetic is part-Assassin’s Creed, part-goth-Illuminati fantasy. Director Liam Steel’s ritualised movement draws out the music’s cell-like structure, finding the dance rhythms and bringing them to the fore, while Jonathan Peter Kenny’s music direction thickens out the vocal textures with the help of accordion, guitar, tambourine and violins. Only a vibraphone, whose glottal-stopped grunts are the cousin of a MIDI-synthesizer, is a misstep.

In a pre-performance interview, Kenny overplays the Oxbridge tradition of Josquin performance. It’s not all polite and wan (just listen to Jordi Savall’s accounts). But there’s certainly room for this rougher, leather-and-tattoos take on music which, 500 years later, is still the stuff of life, death and sex.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in