The 250th anniversary of the landing of James Cook on the rocky shore of Kurnell 250 years ago yesterday passed barely noticed bar a few newspaper articles. Such commemorations as were planned by the Morrison government and others have been cancelled by the Wuhan virus lockdown, but one can’t help but feel the Prime Minister is breathing a sigh of relief that is so: he hasn’t had to justify recognising the foundation stone of our nation to the woke, Aboriginal activists and the black armband industry.

The Australian’s resident historian, Troy Bramston, tweeted yesterday “James Cook was one of the world’s greatest explorers and his voyages of discovery had an enormous impact on navigation, geography, commerce, knowledge of indigenous peoples, and it is important that the 250th anniversary #OnThisDay be remembered for good and ill.”

Well, it was certainly remembered for the ill.

Even the State Library of NSW, which has probably the best collection of Cook manuscripts and relics in the world, could only put on a black armband to mark the day itself. Its Cook commemoration web page is not about the 1970 celebrations, but about the protests of a few hundred Aboriginals against the celebrating.

But for sheer over-the-top black armbandism it’s hard to go past The Conversation. On Wednesday the universities’ struggling propaganda sheet, and supposedly impartial mouthpiece of Australia’s academic community, gave a bitter taste of what Scott Morrison –- who just happens to be the Member for Cook representing Captain Cook’s landing place, the “birthplace of the nation” as Sutherland Shire Council used to boast –- what he could have expected had he made a big fuss of the anniversary. It was a Cook special edition with a cluster of articles and an interactive package for home-learning children to play with. But not one of the Conversation pieces were positive about Cook and his exhibition. To the ivory tower dwellers, Cook was an agent of imperialism, an invader, agent of violence and not peace, and generally a Bad Thing. Cook certainly did not “discover” Australia, and his coming was all bad for the natives. Even the man Botany Bay was named after, botanist Joseph Banks, copped a caning for his alleged crimes.

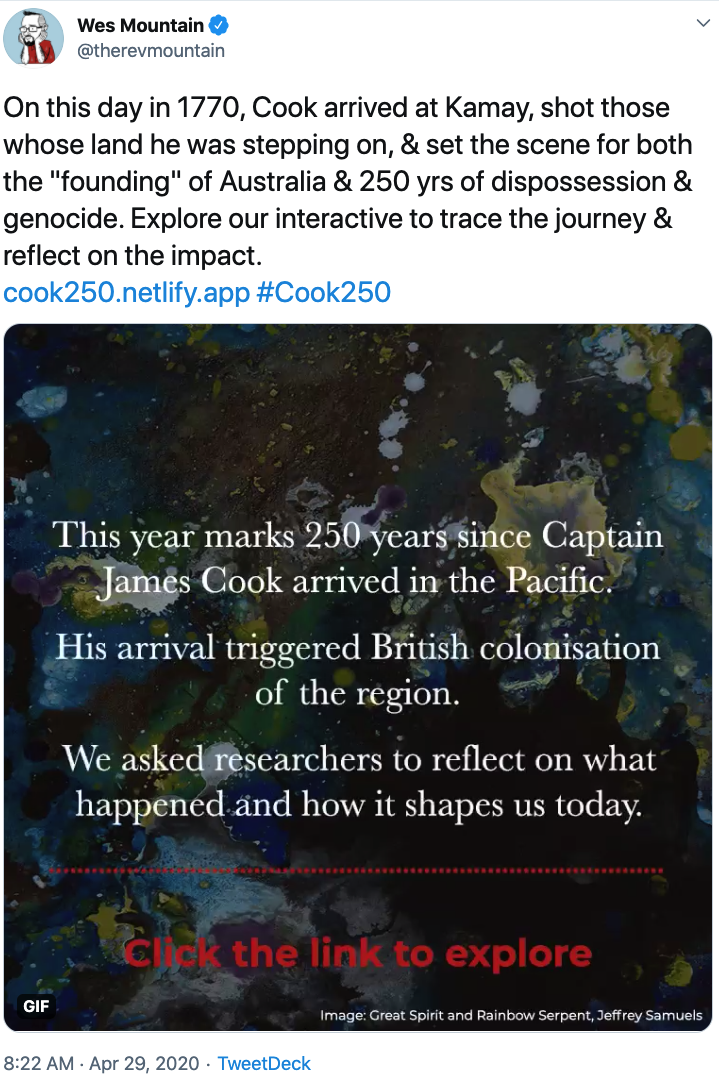

Just take a Captain Cook at this tweet from the Conversation’s multimedia editor promoting the Cook special: “On this day in 1770, Cook arrived at Kamay [Botany Bay], shot those whose land he was stepping on, & set the scene for both the ‘founding’ of Australia & 250 yrs of dispossession & genocide. Explore our interactive to trace the journey & reflect on the impact.”

So much for a fair and balanced — and taxpayer-funded — exploration of the first great exploration of our eastern continent.

Even the conservative Morrison government couldn’t be positive. The centrepiece of the official commemoration of 1770 is a website, www.endeavour250.gov.au , which clunkily and self-consciously tells a story predominantly from the Aboriginal side rather than focusing on, let alone praising, the heroism of Cook, Joseph Banks and the crew and scientists aboard HMS Endeavour 250 years ago. Even the Prime Minister’s press release to mark the day was mildly positive about Cook the explorer yet almost grovellingly apologetic in tone, bending over backwards to put an Indigenous slant on the commemoration. The official ambivalence about the day and its significance is palpable, but the woke media and academia won’t even give credit for that.

Why can we be honest with ourselves, and celebrate the 250th anniversary as enthusiastically and positively as we celebrated the bicentenary in 1970? Pace, Troy Bramston, but the good is good indeed.

On 29 April 1970, tens of thousands flocked to Kurnell on a brilliantly sunny autumn day to join the Queen, Prince Philip, Prince Charles and Princess Anne, Prime Minister John Gorton and NSW Premier Robin Askin in watching Cook’s landing re-enacted. It was the culmination of months of bicentenary events around the nation and mounting Cook fever (for a year in the lead-up the Sydney Morning Herald published daily extracts from Cook’s journal which children dutifully pasted into exercise books), a celebration not of the first discovery of Australia (the Dutch did that), but a great man, a courageous expedition that almost met its fate on the Great Barrier Reef, and its discoveries leading to the European settlement of Australia from 1788. A huge throng of happy, cheering Australians lined Botany Bay were – for all the Donald Hornes and Manning Clarks of the world back then – very comfortable in the own skins, proud not only of their national identity as Australians but of their European, specifically Anglo-Celtic, heritage. We had then the highest standard of living in the world, and we knew that sprang from the kernel of Cook’s visit two centuries before.

Many wore Cook kitsch, like the cardboard Captain Cook tricorn hats handed out by Mobil service stations with every tank of petrol seen on the heads of young boys neatly turned out with short back and sides (hippy culture was yet to penetrate the suburbs) or trousers tucked into long socks to imitate 18th-century knee britches.

I know because, aged almost eight, I was one of them.

That was just the day. That night, Sydney Harbour was ablaze with lights from hundreds of boats large and small, and many thousands more lined the foreshores to watch, by the standards of the day, a stupendous fireworks display, with the centrepieces being the Royal Yacht Britannia and especially the international collection of tall ships lining Circular Quay, brilliantly floodlit and welcoming visitors. While Google and YouTube inexplicably have next to no record of that day, the excitement, the colour, the spectacle left indelible memories on all those who were there.

We who were there celebrated that day, and that event, because we had no doubt that James Cook was a Very Great Man who rose from very humble origins, a personification of the Australian egalitarian self-image., To us, his landing on our shores was a unquestionable Good Thing for Australia and the world. Because his 1770 landing started our nation’s story. Because it brought Western civilisation, learning and culture to those shores. And because the Australia of 1970 was fiercely proud of its past and very optimistic for its future – Australia Unlimited. We knew where we’d been and we knew where we were going. It was only later, after 1972, that we started to lose our way and certainty ended.

That’s not to say Aborigines and their subsequent suffering as a race were ignored in 1970. But back then, we saw Western Civilisation as, well, civilising, and were convinced that Aboriginal Australians gained far more than they lost by being part of it. Nobody ever claimed that European settlement was perfect. But almost everyone then believed – and some of us still do believe – that the wrongs done in our first two centuries were far, far outweighed by the good. As Askin put it on the day, “The Aborigines made some resistance and suffered from their contact with our culture. We are now trying to restore what they inevitably lost from moving out of the Stone Age and into the machine age.” We have, rightly, been trying to restore what was inevitably lost ever since, committing tens of billions of dollars to the effort every year, but it’s never enough to satisfy the Aboriginal activists and black armband-wearing whitefellas.

Because of how it’s been commemorated and the Wuhan virus, this 250th anniversary of Cook’s Australian landing will quickly be forgotten, buried deliberately by those who now write our political and historical narratives and those who fear their vitriol and opprobrium. But it cannot be allowed to disappear without at least someone saying, proudly, that the Australia of 1970 was a good-hearted place inhabited by good-hearted people. If only it, and its values, were still here today, we would be a better nation for it.

It’s only the jaundiced, bitter, ideologue historians and commentators of later years, typified by the Conversation web editor and academics’ offensive and hideously-biased Cook special, who have twisted and distorted 1970 Australia into the culturally-cringing, supposedly racist and monocultural stereotype that justifies their own existence as self-appointed national consciences. They disgracefully have succeeded in sweeping Cook and his achievements into the national attic as something to be ashamed of, not celebrated and honoured.

That the rest of us have let them get away with it is what is truly shameful.

Illustration: National Gallery of Victoria.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in