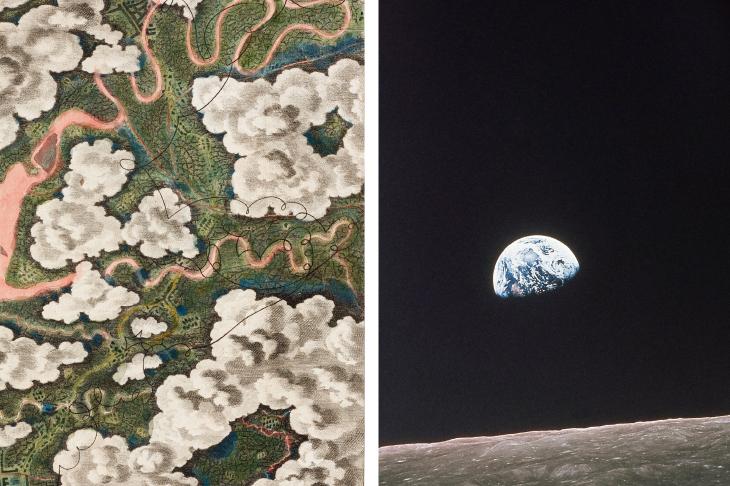

‘To look at ourselves from afar,’ Julian Barnes wrote in Levels of Life, ‘to make the subjective suddenly objective: this gives us a psychic shock.’ The context of Barnes’s remark is the 100-year span in which aerial photography evolved from its 19th-century birth in the wicker cradle of a gas balloon to the miraculous moment in 1968 when an astronaut aboard Apollo 8 took the photograph known as ‘Earthrise’: the darling blue ball of planet Earth rising up over the arid, inhospitable surface of the moon. And all around our little blue globe, darkness. ‘Earthrise’ administered a psychic shock by providing ocular proof of our true position in the universe: insignificant, precarious, lost in the expanding emptiness of space.

All those requiring further proof should make their way to the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne, where an exhibition called At Altitude explores with incongruous calm both the aftershocks of ‘Earthrise’ and the rumblings that preceded it.

In the fourth and smallest room of the show, inside a Perspex cube on a plinth, a thick little volume is open to one of the earliest aerial drawings, made from a balloon basket. The author and artist is Thomas Baldwin and the book is Airopaidia: Containing the Narrative of a Balloon Excursion from Chester, the eighth of September, 1785. An exhaustive account of a single ascent, Baldwin’s 400-page tome is an amazement (though more so online, at archive.org, where it can be admired page by page, than as a teaser at the Towner). Writing about himself in the third person (the subjective suddenly objective), Baldwin luxuriates in the aesthetic stimulation of the aerial perspective: ‘The Imagination itself was more than gratified; it was overwhelmed.’ His enthusiasm — ‘He tried his Voice, and shouted for Joy’ — doesn’t prevent him from making accurate and chilling observations: ‘His Voice was unknown to himself, shrill and feeble. There was no Echo.’

Keeping Baldwin company is an installation, complete with old-fashioned projector and loop of celluloid, of Tacita Dean’s short film, A Bag of Air (1995). The artist ascends in a hot-air balloon to fill a large clear plastic bag with air from the ether, a happy absurdity partially explained by a dreamy voice-over offering alchemic instructions for the preparation of an elixir ‘capable of treating all disharmonies in the body and the soul’. At the start of the film we see the black shadow of the balloon — another bag of air — as it moves across the ground below; at the end the inflated plastic bag is held up against the clear blue sky. The contrast between these two arresting images suggests that Dean, whose recent work is currently on view at the Royal Academy in London, has distilled the essence of terrestrial and celestial, body and soul.

The intermittent roar of the propane burner on Dean’s balloon can be heard next door, an appropriate soundtrack for a dozen artworks all keyed to aerial perspective. Simon Faithfull’s 30Km (2003), a 32-minute video projected downward from the ceiling on to a circular patch in the centre of the floor, begins as a selfie, the artist’s arms framing his face as he reaches upward, attaching the camera to a weather balloon, and ends as an abstract wheel of colour as the twirling balloon rises up through the thinning atmosphere. Along the way we get a bird’s-eye view of the south coast of England and an angel’s-eye view of amorphous heavens. The Towner has helpfully constructed a viewing platform, accessed by stairs, so that the gallery-goer may see 30Km, and indeed the rest of the works in the room, from a lofty perspective: some six feet above floor level.

Tucked in a corner on the floor by the stairs is a small black video monitor, with a pair of headphones hanging on the wall nearby. On the screen is Charles and Ray Eames’s famous nine-minute film, Powers of Ten (1977), which widens then narrows perspective exponentially. We start by hovering a metre above a couple picnicking in a lakeside park in Chicago and zoom out until we’re a hundred million light years from Earth — ‘the limit of our vision’, intones the narrator. The black screen is flecked with a few white pinpricks, and the narrator’s gung-ho American voice is tinged with awe: ‘This lonely scene, the galaxies like dust, is what most of space looks like. This emptiness is normal; the richness of our own neighbourhood is the exception.’ The Eames film pushes the ‘Earthrise’ perspective to its logical conclusion: we see that our solar system is an insignificant speck in a galaxy that is itself a tiny mote floating in what Milton calls ‘the emptier waste’ of deep space. After zooming in at an accelerated pace, the film swaps telescope for microscope, taking a journey into the cells of the body to discover at the subatomic level ‘a vast inner space’, an emptiness within to match the emptiness without.

The mind reels. But here we are, still in Eastbourne, earthbound despite the artwork on display. What have we learned from our brief transit? That up and down, like in and out, are meaningless terms once you’ve escaped the grip of gravity — what counts is near and far. We associate altitude with solitude and freedom. Liberated by flight, we look down and see our lives mapped out on the surface of the planet, we see ‘the richness of our own neighbourhood’. A marvellous early photo taken from a balloon by Percival Spencer shows a crowd at Wolverhampton gathered around the boundary of what looks like a cricket pitch for some sort of ceremony — the mystery of the image is part of its appeal: what are those wacky humans up to?

The great French portrait photographer Nadar claimed credit for taking the first aerial photograph, from a leaky balloon some 80 yards above a village on the outskirts of Paris, early one cold autumn morning in 1858. This success did not lead Nadar down a new career path. The possibility of making art out of the view from the heavens seems not to have occurred to him. He did take out a patent on a ‘new system of aerostatic photography’, but the impulse was purely mercenary. He was thinking about the feasibility of conducting land surveys, and also about military reconnaissance.

In the gallery next to At Altitude, a stark reminder of the other benefits of combining flight and photography: Omar Fast’s 5000 Feet is the Best (2011), a grim 30-minute film about drone warfare. Officers at a command centre near Las Vegas, Nevada, fly Predator drones over faraway countries, survey the landscape with minute and pitiless precision, and rain death from above.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in