Here we go again. Partridges in pear trees. Lovely big Christmas turkey. The Queen’s speech. And then, at some point during the Yuletide season, some version or other of Dickens’s ghost story A Christmas Carol.

This year’s glut of Scrooge stories includes the Old Vic’s major production starring Rhys Ifans (reviewed by Lloyd Evans in last week’s Spectator) and Michael Rosen’s retelling of the tale, Bah! Humbug! There is a new film, The Man Who Invented Christmas, featuring Christopher Plummer as Scrooge and Dan Stevens, he of Downton Abbey fame, as Mr Dickens himself. It plots the months running up to the publication of A Christmas Carol in Yuletide 1843. It’s all very nice and jolly, if you fancy Dan Stevens as Dickens clowning around with children, or demonised by his own characters.

But while we may thoroughly enjoy the fictitious world of Ebenezer Scrooge and his ghosts, I am beginning to wonder if it might be time to say bah, humbug! to the old-fashioned pity fest surrounding Tiny Tim and his modern-day equivalents. These are the adverts we see on daytime TV and the links on social media featuring famished children and dismembered and traumatised people, not to mention blind folk staring vacantly into the camera, usually accompanied by agonisingly slow, depressing music. And just like Tiny Tim, these messages are designed to evoke the maximum pity (and make us give the maximum amount of money), telling us that if we don’t display empathy by ‘liking’ or sharing we are somehow heartless human beings. Virtue seems to be attached to bragging these days.

Now, let’s be clear. I am not suggesting for a moment that we should not help those who need it — financially or otherwise. On the contrary. We all need to attend to our social consciences at some point in our lives. But I am proposing that we might want to be more careful about how we portray those we are helping, and not turn them into objects of pity. This is not because we don’t care but because if we continue to portray disabled people in the manner of Tiny Tim, or Clara, Heidi’s friend in a wheelchair, we are reinforcing in the public mind the idea that anyone in trouble is a tragic victim rather than the self-empowered and independent individual we would all like to be. This year’s cloying and depressing BBC Children in Need was a prime example.

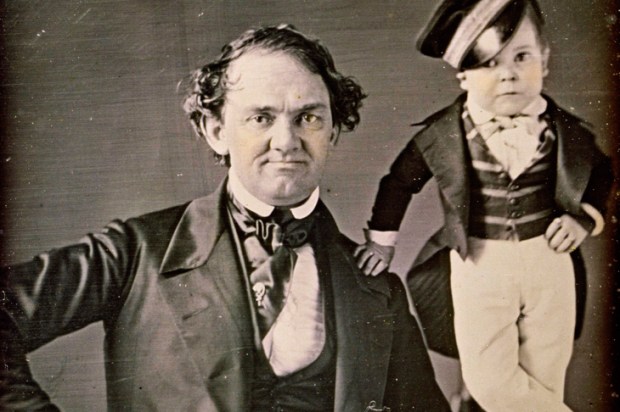

Of course, it’s hardly surprising that Dickens — and many other 19th- and early 20th-century novelists — would use Tiny Tim in this way. At that time, any physical or mental impairment was seen as a burden — something that should be hidden and pitied — or a signal of retribution. Just think of Rochester going blind in Jane Eyre, or Louisa M. Alcott ensuring Beth dies of some unknown disease. Victorians defined disability as something that prevented you from participating in the new industrialised society or, more importantly, from working and contributing to society. Just think of workhouses. But this is exactly my point. We are not in the Victorian age, and it is time to update our notions of disability.

After all, even Dickens adapted his descriptions of disabled people after having been told off by a lady of restricted growth, who threatened legal action. Dickens wrote back, apologising profusely. ‘I am most exceedingly and unfeignedly sorry to have been the unfortunate occasion of giving you a moment’s distress.’ In response, in Our Mutual Friend he created Jenny Wren — a woman with scoliosis and restricted growth who coped with the social and physical adversity of her condition.

So while we absolutely can and should enjoy A Christmas Carol for its brilliant fantasy and description, and we should have concern for the most vulnerable people in society, the pity angle, or even the superhuman angle, are unnecessary in this day and age. While Tiny Tim may be for ever in our hearts, perhaps current-day emblems of disability should be kids who’ve got their first bendy artificial leg, or have simply had a ramp put in at the local train station so it is easy to get to town. It probably doesn’t make great drama, but it does make things more realistic.

At the end of The Man Who Invented Christmas, the character of Charles Dickens says to his assembled family gathered around the Christmas tree, ‘In the season of Hope, we will shut out nothing from our fireside and everyone will be welcome. Merry Christmas, one and all.’ And God bless every Tiny Tim, without the package of pity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in