In recent weeks, North Korea allegedly developed a hydrogen bomb and hangover-free booze. This would be a worrying combination in any government not widely thought to have the force projection of an aggressively drunk toddler with a bag on its head. North Korea is often portrayed as a cartoon state — something sustained by Kim Jong-un’s propensity to execute rivals using anti-aircraft guns. Announcing the discovery of unicorns in 2012 didn’t help, though it was comparatively mild for a state media agency partial to statements like: ‘South Korean President Lee Myung-bak is a rat who should be struck with a retaliatory bolt of lightning.’

North Korea’s Punch and Judy bluster makes us laugh, but at times that leads us to discount the regime’s depravities. The journalist Robert S. Boynton’s The Invitation-Only Zone corrects this, offering a thoughtful study of North Korea via an account of one of its more sinister practices: state-sponsored abductions of Japanese citizens.

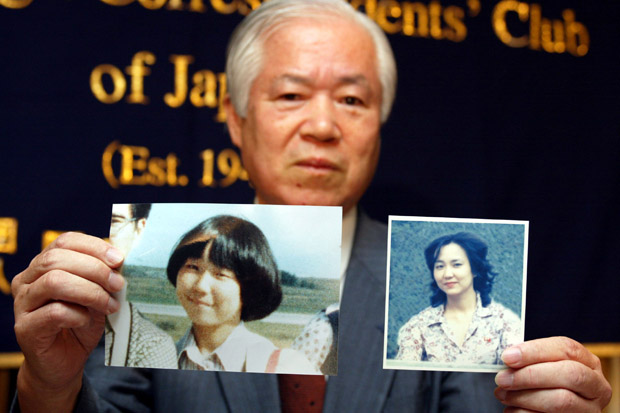

These disappearances were considered ‘urban myths, akin to alien abductions’ in Japan, partly because they seemed so distinctly Bond-villain-like. Yet from the 1970s, North Korean commandos raided Japan’s coastline, grabbing young Japanese — often amorous couples at seafront beauty-spots — and bundling them, drugged, into boats configured to avoid sonar detection. The abductees woke in North Korea and endured 18 months of ‘re-education’ in isolation before being reintroduced to their partners, married, and encouraged to procreate in a strange new world — not, one assumes, how most thought their dates would pan out.

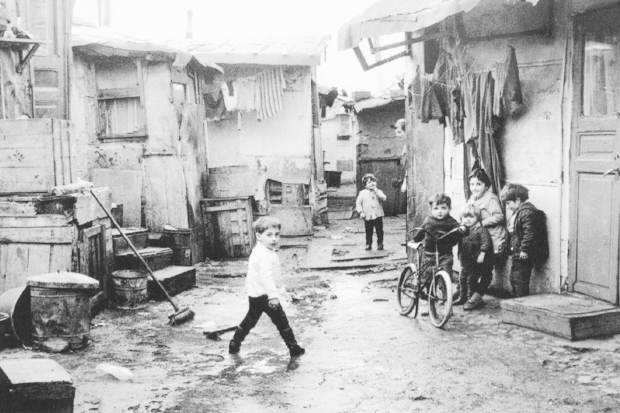

Boynton’s interviews with abductees offer a rare picture of life in this closed state. Japanese abductees were better off than North Koreans, living in ‘Invitation-Only Zones’ — ‘gated communities’ (of sorts). They were under constant surveillance. Minders oversaw every aspect of their lives, escorting them to shops, their children to school, and requiring a journal to be written to give the minder access to [their] thoughts’. Abductees woke each morning to ‘the loudspeaker that is installed in every North Korean house’. Rations were delivered three times a week — ‘the regime’s primary means of social control’. They maintained ‘ideological health’ by ‘weekly “lifestyle reviews”, during which each member of the community reflected publicly on his shortcomings’ — a kind of upside-down PMQs. Abductees lost all hope of returning home.

Boynton, like the victims of abduction, struggles to understand North Korea’s rationale. ‘Perhaps the oddest aspect,’ he writes, ‘is how little the regime benefited.’ Although abductees initially taught Japanese ‘language and customs to spies’, this ended in 1987 after being revealed by a turned agent. Most abductees were given ‘busywork’. ‘There was no single motivation,’ Boynton writes. ‘The most plausible explanation is that the abductions were a small part of a larger plan to unify the two Koreas, spread Kim Il-sung’s ideology throughout Asia, and humiliate Japan.’

Boynton illuminates those motivations by placing the abductions in historical context. The Invitation-Only Zone moves fluidly between accounts of individual abductees’ experiences and the history of Japanese regional geopolitics, from the Meiji era’s re-engagement with the world to Japan’s colonial expansion into South East Asia from the late 19th century until its 1945 surrender. Japan’s ruthless 1910 annexation of Korea, the resistance to which (along with Stalin’s patronage) pushed Kim Il-sung to power after the second world war, prompts a thoughtful consideration of North Korea’s founding ideologies.

The abductions were finally admitted by the Japanese and North Korean governments in 2002, and a number of abductees repatriated. The abductions — and the Japanese government’s hidden knowledge of them — prompted a national scandal, assisting the hawkish Shinzo Abe to become prime minister. Culturally, Boynton argues, the acknowledgement was ‘Japan’s 9/11’: the ‘sudden realisation that the world was more dangerous than it had thought’.

But the abductions picked at deeper cultural issues: Japan’s fraught relationship with the Korean peninsula, and the persistent tug in Japanese politics between the need to redeem colonial sins and a bellicose vision of its future. Following last year’s renunciation of Article 9 — the 1947 constitutional ban on war-making that was a liberal rallying cry and conservative bête noir — Japan’s regional politics are again in the spotlight. Boynton’s lucid, intelligent book is an important contribution to our understanding of them. Or, as North Korea might put it, ‘a sordid hackwork of rubbish media’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in