The much-lamented journalist and bon viveur Sam White, late of the rue du Bac, The Spectator and the Evening Standard, who lived in Paris for over 40 years, once wrote an affectionate portrait of his adopted home that opened with the defiant words, ‘Yes: I like it here.’ As a short review of the city it was perfect. Longer accounts that say less are published every year and must run by now into thousands of volumes.

A glance at the map shows why Paris — ‘most sublime of cities’, as Luc Sante terms it — continues to attract such devotion. There is the twisting shape of the river, cutting the city in two, the islands that form the original nucleus — defensible against Roman or barbarian armies — the heights of Montmartre, the line of the city walls, marked more clearly now by the péripherique ring road, and the 20 enclosed arrondissements, their numbers distributed in a chaotic jumble until one traces the pattern of a coiled snake with its head at the centre. This is a model railway of a capital city, small enough to be crossed comfortably on foot, a magical playground in which to play the game of getting lost for as long as possible in the course of a leisurely day.

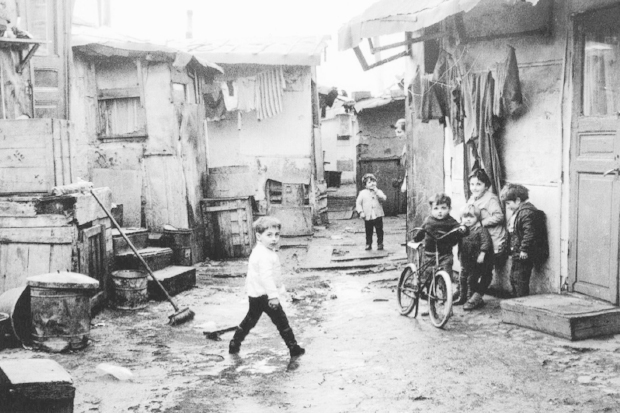

Luc Sante, who is visiting professor of writing and the history of photography at Bard College, New York, has put together an exhaustive and sometimes bewildering collection of anecdotes and snapshots that commemorate the life over several hundred years of the city’s underclass. He argues that Paris embodies the nation’s revolutionary instincts. ‘The Parisians,’ he writes, ‘have historically shown an extraordinary willingness, and even eagerness, to fight authority in the streets… Even today [the city] continues to serve as a theatre for every sort of demonstration and strike.’ He presents the tradition of anarchic violence as evidence of a continuing struggle for liberty, and concentrates on the eastern quarters, disdaining the wealthier areas to the west.

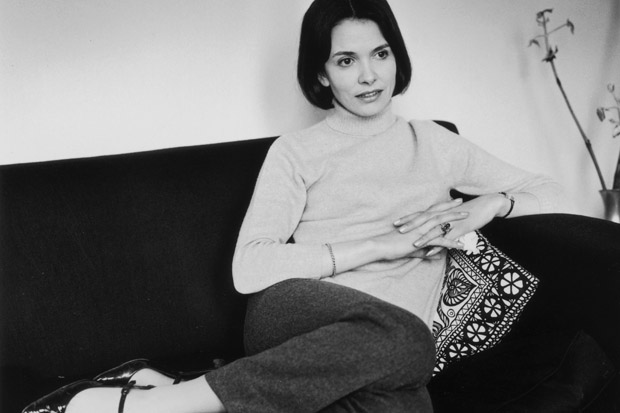

Elaine Sciolino, like Sam White, is a foreign correspondent. She is, she tells us, from ‘the tough side of Buffalo’, New York, and is the daughter of an American-Sicilian who supplied her home town with Italian delicacies. Her ‘only street in Paris’ is the rue des Martyrs in the 9th arrondissement, running downhill from Montmartre and Sacré Coeur. Sciolino has an apartment round the corner on the rue Notre Dame de Lorette. Several books have already been written about the rue des Martyrs, which was once described in a British Sunday newspaper as ‘one of the world’s great shopping streets’, and Sciolino was first attracted to the street by its food shops. Her account of living in ‘the 9th’ today concentrates on the shopkeepers, an assortment of her neighbours and their unremarkable daily lives.

Sante is dismissive of the Sciolino approach. In his view, Paris has become ‘a brand name’, its revolutionary past laminated by ‘planners, developers and accredited consultants’. These powerful interests distribute wall plaques and brass noticeboards and are intent on dismantling a historical city and reassembling a theme park — an acceptable addition to the visitors’ ‘shopping and dining experience’. In search of a more authentic history, Sante has waded around in the archives and emerged with a pile of septic treasures. Here is Balzac:

One of the most distressing of spectacles is the appearance of the Parisian population, a people horrible to behold, pale, wan, sunburned. Their twisted and contorted faces exude through every pore the desires, the vices, the poisons with which their brains have been swelled. They wear masks stamped with the indelible sign of panting greed.

Sciolino gives us Edith Piaf, the ‘Hotel Amour’ (rooms by the hour) and the pleasures of unpasteurised butter and white asparagus. Arianna Huffington drops in and the ladies go clothes shopping together. Sante counters with tales of prostitution, syphilis and the formation under Napoleon III of a special police squad, the groupe des homos, which eventually busted the Hotel Marigny, just behind the Madeleine, a brothel that was notorious for supplying minors for adult men. Here in 1918 the cops arrested 24 underage boys and 24 adult males. The latter included ‘un rentier, 46 years old, 102 Bvd. Haussmann, name… Marcel Proust’. Sante’s examples pile up. He resurrects hags, scabies, disfigurement, human lives reduced to a sub-human level, centuries of public execution by guillotine, and mob butchery in the courtyards and cloisters. As the horrors unfold over the centuries it is hard to decide which is worse, Parisian civil war or peace. An illustration from 1851 by Paul Gavarni shows an aged fille de joie accepting a coin from an elegant gentleman and blessing him with the words, ‘May God keep your sons away from our daughters.’

Occasionally the two visions overlap. Both authors write of the pleasures of

loitering in bookshops on the rue des Martyrs, but Sante’s bookshop (naturally) has closed, whereas Sciolino logs three bookshops that are still open, and mentions the vital role played by retail price maintenance in defending the central importance of le livre in the nation’s culture. Sante notes that rue Notre Dame de Lorette, Sciolino’s home, was once selected by Zola as the gateway to sordid encounters.

Surprisingly, Sciolino, living with her family in a foreign city, gives us nothing about the routine small change of Parisian life, the politics of the school door, the problems of parking or the difficulties in finding an affordable apartment. Instead, we meet a cast of ‘colourful locals’. One is never quite sure whether the latter are pleased to see her or are actually trying to escape from her obsessive curiosity. But she is a dedicated reporter, determined to uncover something new, and her pleasure in observing the little life of her surroundings is infectious. Sante’s more polemical raw material sometimes reads like a bundle of unedited lecture notes. And he has been ill-served by his publishers; one needs a magnifying glass to appreciate the significance of many of the well-chosen illustrations, and the captions are frequently inadequate or misleading.

In his conclusion Sante relapses into the opaque assertions of ‘psychogeography’, often a fashionable synonym for bad travel writing. This is the self-absorbed world of those who have nothing to tell us because they have experienced so little; of authors who rarely use one word when 19 will do. His best chapters are anchored in the reality of la rue and the political importance of the Paris mob. (Although by insisting on the noble aspirations embodied in the violence of the underclass, and ignoring the ‘reactionary’ western areas of Paris, he risks replacing one romantic historical legend with another.)

The two books make a strange contrast. Luc Sante and Elaine Sciolino are both Americans. Sante, who was born in Belgium and has never lived in Paris, has disinterred the entrails of the city. Sciolino, who frequently refers to her Sicilian roots, has lived there for over a decade but nonetheless retains the excitement of a newcomer. She reveals some of the life that people continue to live behind the façade of Sante’s ‘theme park’.

Both writers have responded to the subconscious electricity of Paris. On one level, Paris remains chillingly exclusive, its bloody-minded citizens mocked by their fellow countrymen as Parigots — smug, patronising and entitled. But despite this, Paris continues to fascinate every literate westerner. Even the names of the Métro stations — Voltaire, République, Convention, Victor Hugo, Concorde, Bastille, Austerlitz, Stalingrad — evoke the political, moral and military battlefields of a nation, a continent and a civilisation.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

'The Other Paris', £25 and 'The Only Street in Paris', £16.99 are available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in