Which of Wagner’s mature dramas is the most challenging, for performers and spectators? The one you’re seeing at the moment, seems to be the answer for me. The better I know them, the more apprehensive I get about whether I can rise to their level, and whether the performers can, and whether we can pace ourselves and not flag at the prospect of the last act, in most of them the greatest and most exhausting. In the end, though, I think Tristan und Isolde takes the biscuit. It’s a matter of gratitude, almost, if the Prelude isn’t as overwhelming as it naturally tends to be. At Longborough this year it wasn’t, and I was duly grateful. The whole of Act I was a slightly slow burn, in spite of the torrents of marvellous sound produced by the passionate Isolde of Rachel Nicholls. It’s rare indeed that one even imagines complaining about a Wagner soprano being too loud, but there were moments when Nicholls would have been more at home in Covent Garden than in Longborough. For once Isolde had a Tristan who was on a level with her, in volume and in dramatic intensity. Peter Wedd is the finest Tristan I have seen and heard since Siegfried Jerusalem in his prime, and in certain respects he is clearly superior; in fact, given the chance to sing the role a few more times, he may be the most potent interpreter of the part that anyone can remember.

Neither Nicholls nor Wedd have probed the depths of these roles yet, but the thought of their continuing to sing them is very exciting. They were guided by Anthony Negus, the presiding Longborough spirit, and without question a great Wagnerian. How long it is since London has heard conducting on this level! And why? Negus’s career seems to be a weird recapitulation of his great mentor Reginald Goodall’s, but it is hard to envisage him being such an awkward customer, making all the more frustrating our having to endure the mediocre performances in the capital, or in Bayreuth. Negus’s most impressive feat in Tristan was his ideal shaping of Act II, the great duet for once exceeding all expectations in excitement, power and profundity. The lovers’ excursions into metaphysics and linguistic analysis were integrated into their less esoteric raptures as they almost never are, and Brangäne’s warnings were gloriously voiced by Catherine Carby and the superb orchestra. Only the King Mark of Frode Olsen seemed both stiff and gruff, so that he answered too readily to Isolde’s scathing Act I descriptions of him.

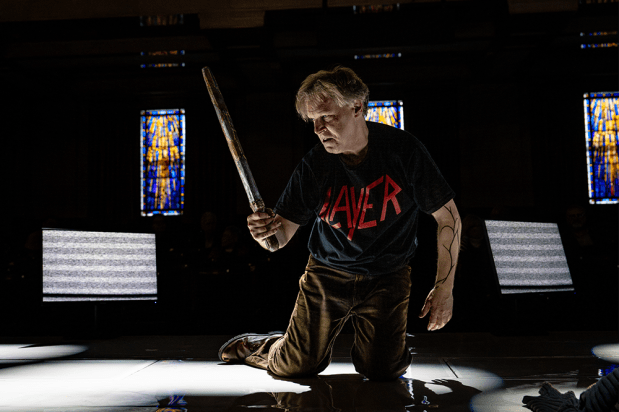

The production: well, it wasn’t good. Carmen Jakobi at least had the characters relating to one another, and the Act III fights were well planned, if less well executed. But at the climax of the Prelude a male and female dancer entered and did what dancers do, alerting us to their possible return. And they put in appearances at many crucial moments, enacting some of the duet in more physical terms, and stripping to body stockings. Infuriating. Though after their third or fourth entry, I closed my eyes for about two minutes for each of their returns, and they were gone. However trying they were, were they as annoying and intrusive as the Royal Opera’s long-lasting stag party or night hunt, not to mention its previous appalling production? Or Bayreuth’s last one, or the anaemic Glyndebourne affair? I feel sorry for anyone who wasn’t exalted by this account. It left me, naturally, hardly able to cope with Act III, which, heard separately, I regard as the greatest of the three acts and one of the most astonishing achievements of any artist. Wedd was tireless, lovely of voice and always clear in articulation. Even more than the Ring, I think, Longborough’s Tristan will remain a yardstick in my memory.

Continuum Ensemble mounted an enterprising weekend of ‘music of a lost generation’, of which I attended the first concert, which included two brief operas by Hindemith and Ernst Toch, and two pieces by Weill. The planning of the weekend was Michael Haas’s, and so continued in the spirit of his Decca series of Degenerate Music. Hindemith’s There and Back (1927) is one of his quarter-hour operas, and would fit well into a Tête à Tête festival, with its inspiration being at about the same level as many of the pieces we hear from them. Much the same goes for Toch’s Egon and Emilie (1928), a long and demanding soprano solo, stunningly performed by Donna Bateman, uncannily like Renée Fleming 20 years ago. Her husband silently endures her hysterics, and says, not sings, some sensible things when she has disappeared. In the best neoclassic spirit, these pieces are written mainly for winds, and in the extremely resonant acoustic of the small hall they made more noise than I have ever experienced, in a concert or at home. The words of the singers were naturally unintelligible, indeed I mistook the language they were singing in. A sheet with a text of the Weill pieces was helpfully provided, and the first, from ‘Death in the Forest’ (1927), made a strong impression, a long dirge sung by Barnaby Rea. It was good, too, to hear the Mahagonny Songspiel (1927) in an effective performance, so much more enjoyable than the whole Mahagonny opera, and especially than the last performance of it I saw.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in