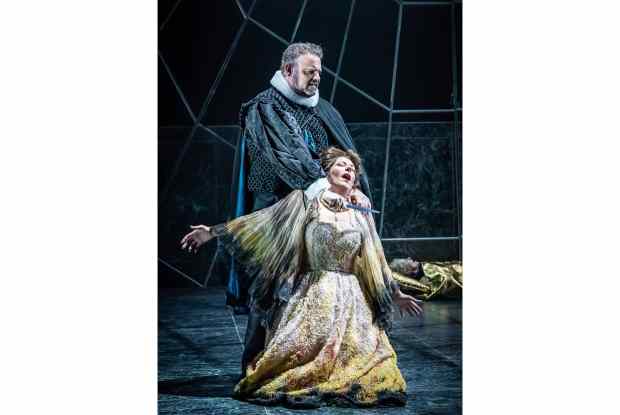

There are a lot of corpses on stage at the end of Charles Edwards’s production of Tristan & Isolde for Grange Park Opera. At this stage in the drama, directors tend to fade out the bloodbath, the better to focus on Isolde’s final dissolution into bliss. But as Michael Tanner argues, Tristan, like the Ring, offers no bearable solution to its central problem, however much the music – that great deceiver – might try to persuade us otherwise.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in