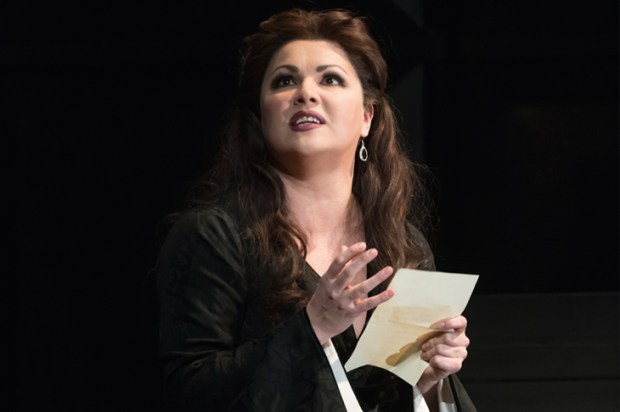

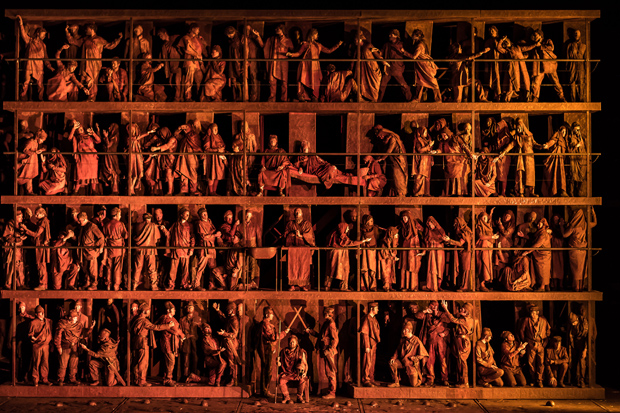

Any adequate performance of Tristan und Isolde, and the first night of the Royal Opera’s production was at least that, leaves you wondering what to do with the rest of your life, as Wagner both feared and hoped it would. What Tristan does — one of the things — is to present an image of romantic love, in both its torments and its ecstasies, which makes everything else seem trivial; and at the same time to undercut that image by asserting the claims of ordinary life, but in the subtlest way.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in