Every musical career has its own narrative, and most of them include at least one comeback. To come back, you first have to go away; then you have to stay away; and finally, when everyone has forgotten your name, you wander nonchalantly back under the arc-lights and wave modestly to screaming fans and waiting reporters. Well, that’s the plan, anyway. As has been discussed here before, the gaps between record releases for all but the most irresponsibly prolific artists have become so wide that simply making another album becomes a comeback in itself. Thus has the currency of the comeback been devalued. Sometimes it feels as though there’s a different one every day. A few of them could usefully have stayed away a little longer.

Just occasionally, though, there’s the real thing. Artist has been silent or underperforming for years, then suddenly pops up with what breathless young critics, reading the press release, call ‘a return to form’. Again, long experience of comeback disappointment makes older and more cynical listeners unwilling to suspend disbelief. We have been caught that way before, too many times. Even rarer than the ‘comeback’ that is a real comeback is the ‘return to form’ that is a real return to form. Last year we had two that I know of, David Bowie (silent) and Paddy McAloon of Prefab Sprout (semi-silent, underperforming). That’s a lot for a single 12-month period, but you never know, there may have been even more.

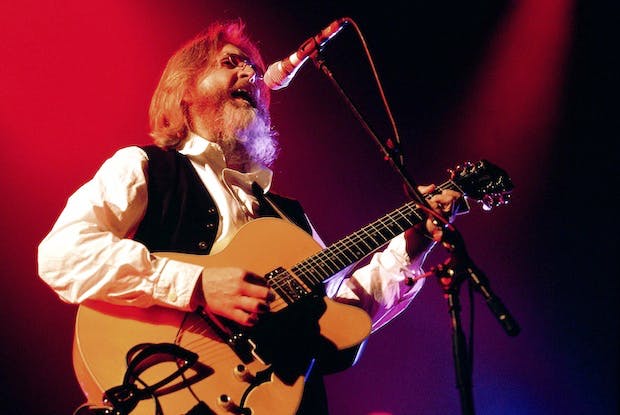

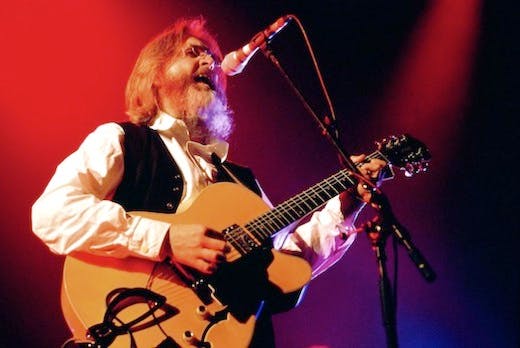

Paddy McAloon of Prefab Sprout Photo: Redferns

Prefab Sprout’s Crimson/Red (Kitchenware) is simply their best record in a quarter of a century. I say ‘their’, but of course it’s ‘his’ now. McAloon recorded the whole thing himself with computers, apparently in a shed. Long gone are drummer Neil Conti (1993) and backing singer Wendy Smith (late 1990s), and even Paddy’s bassist brother Martin hasn’t been heard since 2001. Gradual group disintegration is a familiar symptom of long and inexorable decline, although sad fans like me kept on buying every new album as soon as it came out. Not that there have been many of them. After producing five albums of new material between 1984 and 1990 — two of them cast-iron classics — McAloon had managed only four more since. Andromeda Heights (1997) revealed a disturbing new Stephen Sondheim influence, The Gunman and Other Stories (2001) was essentially a collection of old songs he had written for other people, rerecorded with session musicians, I Trawl the Megahertz (2003) was a single conceptual piece based around a lot of late-night radio listening, and Let’s Change the World with Music (2009) was the home-made demo for an album McAloon was going to record in 1993 but lost heart in.

The earlier days of Prefab Sprout: Paddy and Martin McAloon, Wendy Smith and Neil Conti Photo: Getty

Critics were kind and I played it to death, happy to have anything new from McAloon to listen to, but in truth it was a real barrel-scraper, and releasing it seemed more like an act of desperation than anything else. McAloon, we knew, had suffered health problems for a number of years. He had grown an enormous white beard and walked with a stick. And yet we knew that he was still writing songs, that he had hundreds if not thousands of them stacked up, and was too busy writing more to record the ones he already had. What’s the only thing worse than writer’s block? Not being able to stop?

For with so many songs to choose from, how can you tell which ones work and which ones don’t? From 1990’s Jordan: The Comeback onwards, McAloon distracted himself with great overweening concepts, but quality control was lost. Andromeda Heights had a dozen songs about stars, of which maybe three were worth hearing a second time. It’s notable that Crimson/Red has no overweening concept; it’s just a collection of wonderful songs teeming with musical ideas, with droll lyrics and all the confidence of the early albums. That’s the crucial element: confidence. How easily it can dissipate as the years go by, and how hard it is to regain it, especially when you have endured years of serious illness. And we begin to wonder, how many other great songwriters didn’t lose their talent as they aged, but lost confidence in their talent? Bowie may be another. You feel time has passed you by, and you can’t quite recall why you were any good in the first place. McAloon has shown there’s a way back. The focus is renewed, the talent is intact. It’s a hugely encouraging record for anyone over the age of 50, whether you actually like his music or not.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in