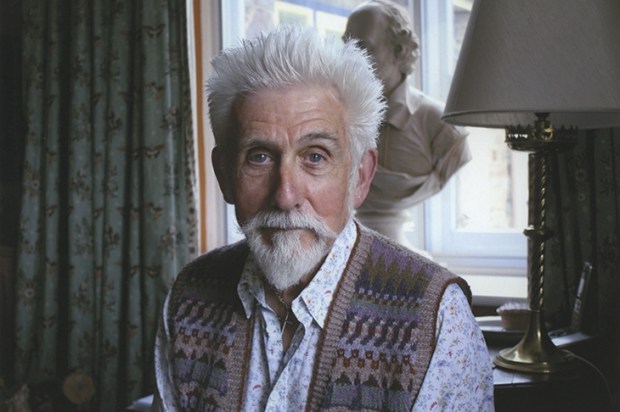

If Carlo Scarpa were as well known as Le Corbusier, modernism might not be so reviled. This architetto poeta grew up in Vicenza, whose 21 buildings by Palladio surely had a formative influence on his fast- evolving artistic intelligence.

Scarpa studied building design at university, but, instinctively disobedient, never bothered with a licence to practise as an architect. So connected was he to his native territory that when Frank Lloyd Wright first visited Venice in 1951 he insisted on Scarpa being his guide. Most of Scarpa’s working life was spent in the Veneto, but he died in 1978, aged 72, in Sendai, Japan, after falling down a flight of concrete stairs. This added his own distinctive chapter to the story of curious deaths of great architects.

Federica Goffi’s finely illustrated book is not a biography nor a formal catalogue. (There is already a comprehensive monograph by Robert McCarter.) Instead, Scarpa becomes an exemplar of very topical ‘creative re-use’. Since he was not a licensed architect, he made few standalone buildings, preferring startling interventions and ingenious adaptations. Thus it is a timely manifesto as we become increasingly aware of how environmentally reckless demolition and new build are. Chemical processes in making one ton of concrete release nearly the same weight of carbon.

Yet concrete became Scarpa’s medium, though glass came first. He began working with the Venini glassworks on the island of Murano in 1932, where he was called a disegnatore, an early example of this title. In 15 years Scarpa designed 300 sophisticated vases, bowls and flasks, reviving ancient techniques but achieving results that are distinctively modern.

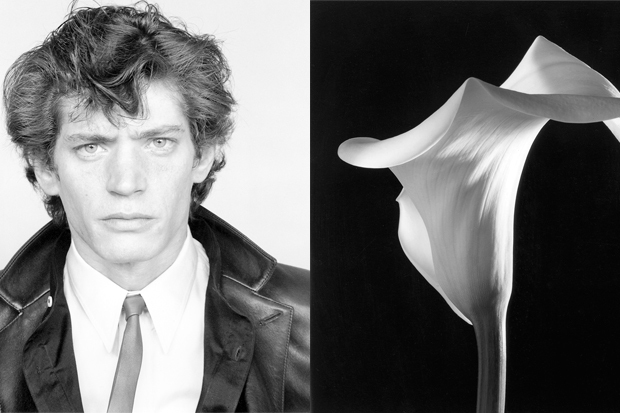

Indeed, Scarpa glass is shorthand for ‘contemporary’, and because his vessels are by no means functional they can be enjoyed for what they are: original and profoundly beautiful. When the Met put on a show of the glass in 2013, it was a critical and popular sensation. ‘Art, craft and science merge,’ said the New York Times’s critic Roberta Smith – neatly defining the modernist mentality as a whole.

Then Scarpa turned to buildings. Olivetti, an office machine manufacturer, was one of the great patrons of designers during Italy’s postwar ricostruzione. In 1957, Scarpa began work on an Olivetti showroom in Venice’s Piazza San Marco. In a small but exquisitely subtle space, typewriters were presented with reverential awe. ‘I’d rather build museums than skyscrapers,’ he wrote. The Negozio Olivetti shows his fascination with joints and spaces: horizontal floor plates do not always meet vertical walls. This is not unsettling: it is a richly satisfying demonstration of spatial complexity, the designer playing with our assumptions about the laws of construction. It is preserved as a shrine.

Scarpa believed the old truth that you don’t finish a building, you start it

Two years later, Scarpa made his dramatic interventions in Venice’s Fondazione Querini Stampalia. In Verona’s Castelvecchio Museum, he uses blue polished plaster to set off a Tiepolo. He always questioned the notion of ‘single author buildings’ and at Venice’s architecture school in the old Tolentini convent, itself a design by the great Vincenzo Scamozzi, he built a heroic entrance in bold geometrical forms.

Verum Ipsum Factum is inscribed there – Giambattista Vico’s belief that ‘there is truth in what is made’. Pass through a dramatic sliding concrete gate to find a magnificent 16th-century door frame in Istrian marble that is laid horizontally. With water features and enfilades of concrete, this is a compact introduction to all the possibilities of architecture. Scarpa said he liked water because he was Venetian.

His most famous work is the tomb for the Brion family at San Vito d’Altivole, near Treviso, ironically completed in the year of his own death. Like Olivetti, the Brions were, through the Brion-Vega electronics business, generous and influential patrons of architecture and design. That celebrated bright red plastic folding radio? It’s Brion-Vega.

The tomb is unlike anything else you have ever seen, more miniature townscape than solemn mausoleum. Vivid Venetian glass inlays contrast with a rambling narrative of serene and sometimes disarming shapes. Only a 5mm skin of concrete covers the iron reinforcing rods, creating an immediate maintenance problem. But the resulting dynamic stains suggest something of the transitory nature of existence. Scarpa wrote: ‘The place for the dead is a garden. I wanted to show some ways in which you could approach death in a social and civic way.’

Because he was so dedicated to the Veneto, in his lifetime Scarpa never achieved the global recognition enjoyed by lesser designers. But his ideas about the layering of history, of re-use and an ‘architecture of multiple authorships’ came to happy prominence in David Chipperfield’s Neues Museum in Berlin, an inspired renovation project completed in 2009 where past and present are indivisible.

Goffi is an Italian academic who has journeyed to the United States and carries the heavy rhetorical baggage that ticket suggests. Critics are forever arguing with one another in her book. Nonetheless, it is a fine memorial to a great creative figure: only the dullest person could fail to be inspired. As Roberta Smith said of Scarpa’s work: ‘If you are open to it, it can radically reshape your ideas about form, beauty, originality and art for art’s sake.’

For Scarpa, modernism was not a style but an attitude. Great buildings are achieved by the artful managing of light and space. He deserves to be better known. He believed the old truth that you don’t finish a building, you start it. I started Goffi’s book, but finished it, too – and felt rewarded.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.