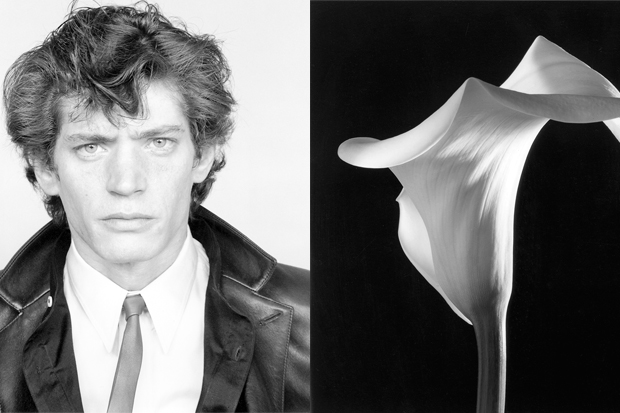

Robert Mapplethorpe made his reputation as a photographer in the period between the 1969 gay-bashing raid at the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street and the identification of HIV in 1983. This was the High Renaissance, the Age of Discovery, the Bourbon Louis Romp, the Victorian imperial pomp, the Jazz Age, the Camelot moonshot, the Swinging Sixties of gay culture in New York.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

An exhibition of photographs — Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium — is at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles,until 31 July. 'Robert Mapplethorpe - The Photographs', £34.00, 'Robert Mapplethorpe: The Archive', £34.00 and 'Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers', £100.00 are available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033. Stephen Bayley’s Death Drive: There Are No Accidents was published last month

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in