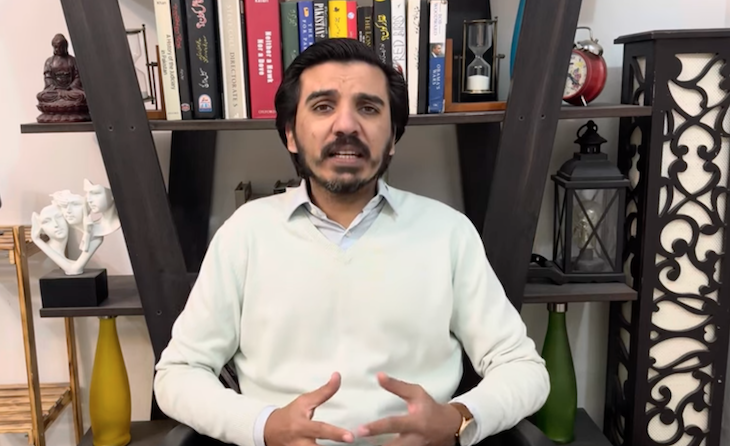

In a cosy Persian restaurant in an Islamabad strip mall, a young man approached Asad Ali Toor for a selfie. ‘I watch your show, I admire your work, thank you for what you do,’ he told the journalist.

Toor’s real crime is speaking truth to power

Days later, Toor was in jail, charged with ‘cyber crimes’ after being interrogated by Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA).

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in