Let the handwringing begin! Long before the polls closed in Tuesday’s off-cycle elections, pundits were already racing to assign blame for another underwhelming Republican performance.

The usual suspects duly took the predictable hits. Legally troubled former president Donald J. Trump played almost no role in the elections, but it was easy to pin lackluster results on him as the GOP’s runaway favorite for the 2024 presidential nomination and the party’s de facto leader. The only major candidate he endorsed, Kentucky attorney general Daniel Cameron, lost to Democratic incumbent Andy Beshear. Congressional Republicans are suffering in the commentary for their recent removal of former House speaker Kevin McCarthy, which drew negative comparison to the Democratic House Conference’s lockstep unity. Anti-abortion activists got slammed for ballot initiatives that passed in Ohio and, earlier, Kansas, reliably red states that nevertheless installed a right to abortion in their constitutions. Cultural conservatives, especially those advocating greater parental oversight of public education, are taking blame for the party’s failure to deliver both houses of Virginia’s state government in concert with Republican governor Glenn Youngkin, who at least until now has been touted as the last viable alternative to Trump for the party’s 2024 nomination.

Democrats, meanwhile, are reading the tea leaves to find an encouraging path forward. Just as they did after the 2022 midterm elections, they are eager to ascribe Republican setbacks to what they mistakenly believe is the durability of President Joe Biden, whose unpopularity — even among Democrats — is difficult to overstate, and whose physical and mental condition is unlikely to improve in the next twelve months.

Regardless of partisanship, the commentary is missing a much more revealing trend: taken as a whole, the 2023 results lurched not so much toward the Democrats as toward divided government. As disappointing as Beshear’s reelection may be for Republicans, he will continue in office facing Republican majorities in both houses of his state’s legislature that are large enough to override his veto power. Youngkin invested heavily in keeping the GOP majority in Virginia’s lower house and capturing it in the state senate, but Virginians made clear that they would rather have him in the governor’s mansion with narrow Democratic legislative majorities to check him, albeit not to the extent that they could override his veto. Michigan, by contrast, revoked Democratic control of its state house, won only in 2022 after forty years of minority status, and returned an evenly divided chamber. Down ballot elections in New York ended historic county-level Democratic rule, continuing a growing backlash against Democratic dominance in that state.

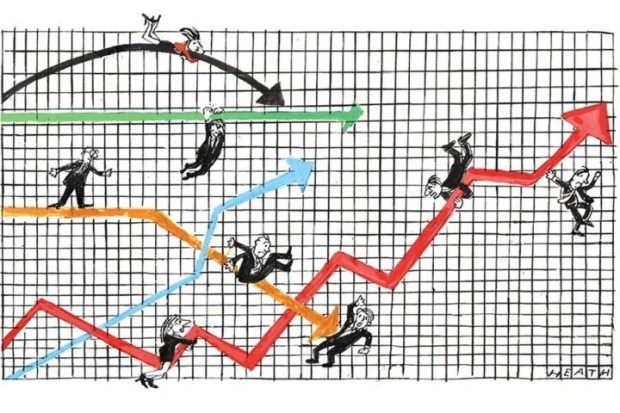

To a degree, these results should only have been expected. Judging by the country’s long-term voting trends, America loves divided government. American voters have returned opposite parties to the presidency and at least one house of Congress for twenty-eight of the last forty years — 70 percent of the time. Nationally, each party controls roughly half of state governorships, with the Republicans currently enjoying a one-capital edge after Jeff Landry captured Louisiana’s governorship to succeed term-limited Democrat John Bel Edwards last month. The Senate, as currently constituted, has a one-seat Democratic majority that includes two senators (one Democrat and one Independent who caucuses with the Democrats) who occasionally act as spoilers of majority rule. The House is slightly more Republican, with a small group of uncompromising conservatives who, as McCarthy found out, can also sandbag the majority if so moved.

What’s the advantage? Divided governments can only pass legislation through compromise, a value that 74 percent of Americans claim to favor, according to December 2022 poll. Among electorally vital Independents, that figure rises to 78 percent. Beshear’s hold in Kentucky is widely attributed to his centrist politics and ability to cross party lines to make productive deals with his state’s overwhelmingly Republican legislature. On Election Day, that proved a more attractive option than Cameron leading an unchecked Republican trifecta in implementing a partisan agenda, possibly including a total ban on abortion, which Cameron has professed to support. Similarly, Youngkin’s more partisan approach to abortion and school policies — the latter having been his key to victory in 2021 — looked aggressive and his electorate reined him in by imposing divided government.

Off-term elections do not always predict general election results, but if there is a lesson to be learned here, it is that 2024 may be a race to the center.

The post Actually, the 2023 elections show voters want divided government, not Democrats appeared first on The Spectator World.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in