Modern nightlife was invented in London around 1700. So argued the historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch, who traced this revolution in city life to its origins in court culture. Medieval and Renaissance courts held their festivities while it was still light outside, but by the late 17th century, aristocrats preferred to party after dark. The trend was rapidly commercialised: a new kind of conspicuous consumer descended on pleasure gardens like Vauxhall and Ranelagh, to eat, drink, stroll and listen to music by the many-coloured light of thousands of oil lamps.

Or you can give King Louis XIV the credit: in 1667 he ordered that Paris be lit up by thousands of candle lanterns, and the idea spread through Europe’s metropolises. Before that, night was a fearful, all-consuming presence, and the main challenge was to get through it, ideally without falling off a bridge or being stabbed. Now that same fear was transmuted into a frisson of mystery and expectation.

Whatever the cause, 18th-century London delighted in illumination. In the 1780s foreign visitors reported admiringly that Oxford Street’s shops kept the lights blazing until 10 p.m. It was a mark of high status to go out in the evening, and people were soon vying to be fashionably late. ‘The present folly is late hours,’ Horace Walpole noted in 1777. ‘Everybody tries to be particular by being too late, and as everybody tries it, nobody is so. It is now the fashion to go to Ranelagh two hours after it is “over”.’

Eighteenth-century writers recorded the thrill of nocturnal adventure – sometimes illicit, sometimes innocent. In one of the most joyful scenes in Boswell’s Life of Johnson, the great lexicographer is awoken at 3 a.m. by men banging on his door. He opens it warily, poker in hand, only to discover his two young friends Bennet Langton and Topham Beauclerk, who have been out all night. Johnson shoots them a wry grin – ‘You dogs, I’ll have a frisk with you’ – and they sally forth to Covent Garden, where the greengrocers are setting up their stalls for the day; then to a tavern, before getting a boat down the Thames to Billingsgate. For Johnson, sleep was the enemy. ‘Whoever thinks of going to bed before 12 o’clock,’ he declared, ‘is a scoundrel.’

A new exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum, Georgian Illuminations, evokes the most spectacular instances of this conquest of the night: the lavish, extortionate light shows and firework displays which delighted the upper classes at their private celebrations and the people of London at public events. Vauxhall Gardens features heavily. Its innumerable glass jars had to be cleaned every day and refilled with whale oil; next, crucially, the wicks were linked together with flax threads dipped in sulphur and saltpetre, so that a few lamplighters could illuminate the whole place in an instant.

Thanks to its candlelit glamour, the Gardens became a centre of entertainment both popular – like the legendary Madame Saqui, who descended a tightrope in a feathered headdress with fireworks going off around her – and sophisticated. The latest paintings were displayed, the latest music performed. Handel and Hogarth had season tickets.

The orchestra stage was itself a leading attraction, an elegant construction twinkling with hundreds of miniature flames. The exhibition has one of the original glass jars and a display of some replicas, though there aren’t any actually lit up, presumably for safety reasons. (Couldn’t they have a couple of volunteers standing by with fire extinguishers?)

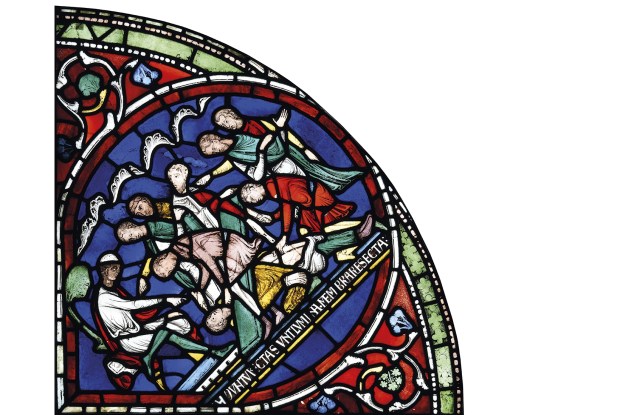

Alongside paintings and drawings of 18th-century light shows, you can see two rare examples of transparencies: tall canvases of wafer-thin linen, decorated with translucent paint so that they can be lit from behind. The paintings, created in 1814 to mark the apparent end of the Napoleonic Wars, show the Duke of Wellington and ‘Peace Destroying the Implements of War’, respectively.

Tucked away in a dark room of the museum, they glow in a manner now redolent of a bus stop billboard, but at the time, displayed from a townhouse window to thousands of onlookers, they communicated an unearthly wonder. Such images, Robert Southey remarked on another occasion, ‘seemed rather to be suspended in air than fixed to an immovable object’. Sadly the museum does not have the original version of an 1813 transparency of Napoleon in conversation with Death as they overlook the Battle of Leipzig. The Sun quipped that Napoleon was ‘now placed in a situation in which all Europe may see through him’. A transparent man, lit by a dying flame.

The year 1814 also witnessed an ingenious display of British engineering and military capacity, costing about £2 million in today’s money, and depicted here in memorable aquatint. All day in Green Park a model ‘Castle of Oppression’ was subjected to a mock siege. As night fell, the castle was entirely hidden in smoke – at which point fireworks went off, the orchestra struck up a tune and the castle was revealed to be made of painted cloth, which fell away to reveal the Temple of Concord, dazzlingly lit up and rotating on a mechanical stage.

The Great Exhibition and the 2012 opening ceremony are all very well, but this was surely the golden age of official public spectacle: wildly expensive, shamelessly jubilant and liable to go completely wrong. In 1749, to mark the end of the War of the Austrian Succession, George II ordered a firework display in Green Park, with a specially commissioned work from Handel and at a cost of around a million pounds today. Rain fell intermittently, ruining the planned display, before a fire broke out in the north pavilion, setting off several cannons which drowned out the Music for the Royal Fireworks. After everyone went home, the Duke of Richmond bought up the surviving fireworks and used them two weeks later at Richmond House. An anonymous etching depicts the Thames shimmering in the light of the rockets and Catherine wheels, while mesmerised spectators watch from their river barges.

The age of illuminations was not just a spectator sport: anyone could put a few candles in their window to celebrate a national occasion. John Henry Newman remembered being five years old and seeing the windows of his house lit up for the first anniversary of Trafalgar.

All this is skilfully evoked under the dimmed lights of the Soane’s exhibition rooms. The only drawback is that it’s over too soon: you can imagine a much bigger show on the linked themes of entertainment, illumination and Georgian life. The cultural ramifications are there to explore: no wonder people who saw these shows thought they were living in the age of enlightenment.

Bright lights will always be synonymous with the big city, but they have lost some of their power to astonish. In 1806 a visitor to Vauxhall called the orchestra stage ‘one of the most beautiful objects that can be imagined’, ‘exceeding all the poets of fairyland and Elysian fields’. Three decades earlier, the protagonist of Fanny Burney’s Evelina, at Ranelagh Gardens, was similarly wonderstruck: ‘The brilliancy of the lights, on my first entrance, made me almost think I was in some enchanted castle or fairy palace, for all looked like magic to me.’

By 1859 that era was ending: Vauxhall Gardens had been surpassed by casinos and music halls and was sold off to property developers. Punch published a facetious elegy, illustrated with a picture of the last waiter weeping as smoke curls away from the last extinguished lamp.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in