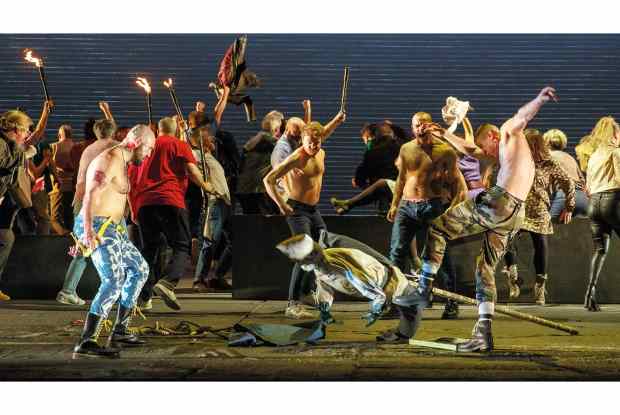

In David Alden’s production of Peter Grimes, the mob assembles before the music has even started – silhouetted at the back, muttering and menacing. Ah, Britten’s mob: simultaneously the source of some of the most electrifying, elemental choral writing since Mussorgsky and a licence for British directors to indulge in premium-strength snobbery. Fully endorsed by the composer, of course: it’s essential to Britten’s artistic schema that we believe the inhabitants of small-town England are only ever one beer away from forming a lynch mob. As their hatred boils over, Alden has them pull out little Union Flags, completely without pretext. There’s no trace of political nationalism anywhere in the libretto or score.

It’s a curious way to read this unsettling opera. Surely it’d be all the more unsettling if we felt that we could be part of that crowd? Instead, we’re reassured that these ghastly provincials are absolutely not Our Sort of People. At least Alden is not aiming for naturalism. Apparently The League of Gentlemen was broadcast in Poland under the title Town of Maniacs and that seems to be the general vibe here. Justice Swallow (Clive Bayley) cavorts in a tutu. The Nieces are a pair of robot schoolgirls from a Japanese horror movie, and Auntie (Christine Rice) is a pinstriped she-dandy straight out of George Grosz. Possibly she’s meant to evoke Radclyffe Hall, who lived in Rye: the kind of seaside town, one imagines, with which opera directors feel more comfortable.

And yet, and yet. Every time I see Peter Grimes, doubts resurface; and every time, genius exerts its tidal pull. It’s just too alive, too right. Britten’s fundamental artistry asserts itself to create a world of salt air and windswept shingle that transcends the attendant silliness, drawing characters who live independently in the imagination long after the curtain falls. Martyn Brabbins conducts, and he was surely born to interpret this music. He whips the ENO Orchestra to peaks of foam-flecked virtuosity, while silences hang like thunderclouds on the horizon. It’s superb.

So, too, are the protagonists (though even the secondary characters – Bayley, Rice, and Alex Otterburn, who plays Ned Keene as a weaselly spiv – are cast from strength). Simon Bailey is a brisk, forceful Balstrode. Elizabeth Llewellyn’s Ellen Orford is motivated wholly by compassion and her voice – which projects a huge, generous luminosity without sounding fierce or forced – is like a patch of sunlight on the roiling sea-and-cloudscape of Britten’s score. Then there’s Grimes himself. Gwyn Hughes Jones’s tone conveys the rawness and the inward rapture of a man whose visions are both blessing and lifelong curse. It’s disturbingly at odds with the way he lunges and snarls, like a Bully XL on a short leash. He’s frightening, but evidently damaged.

At the end, Alden strips everything back. Ellen and Balstrode cling to the edges of a stark, bare set where Grimes, utterly isolated, becomes like Lear or a figure out of Beckett. Again, that tidal pull. All the irritating quirks are scoured away and the production’s underlying strengths coalesce into something primal. The staging dates (though you wouldn’t guess it) from 2009, and it launches an ENO season in which seven out of nine productions are revivals – thanks for that, Arts Council! Yet despite everything, ENO refuses to be vandalised. Peter Grimes shows a major international company operating at full artistic power.

When Alden’s Grimes premièred at ENO in 2009, Laurent Pelly’s staging of L’elisir d’amore was midway through its second revival at Covent Garden, and by some curious alignment of the stars it’s on again now. Back then, Michael Tanner wondered ‘how a comedy can be so relentlessly good-natured without being annoying’, but after a decade of cynicism a sunny operatic romcom about basically nice people feels almost like a radical statement. Pelly’s 1970s Italian village, with its hay bales, Vespa scooters and canine cameos (can’t go wrong with an onstage mutt), is still attractive and conductor Sesto Quatrini gives a rustic, earthy undertone to a generally stylish account of the score.

Meanwhile, you’ve got an Adina (Nadine Sierra) who caresses her melodies as sweetly and coquettishly as she twists her hair. There’s a droll little bantam of a Belcore (Boris Pinkhasovich) and as Dulcamara, Bryn Terfel – not the vocal force he was, it’s true, but oozing plausibility and rolling his words as if he were tasting a particularly succulent Valpolicella. And at the centre of it all, Liparit Avetisyan is Nemorino: a puppyish, utterly endearing boy-next-door with a voice of salted caramel. It does the soul good to hear an audience erupting in genuinely affectionate laughter, but the ovation after ‘Una furtiva lagrima’ was explosive, and it startled the little girl who’d fallen asleep in the seat in front of me. Her first opera, perhaps? Hopefully she enjoyed it. You certainly will.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in